The intention(s)

The intention(s) to see the lived live(s) of Indigenous Artist Tools during:

This is what happens when you perform the memory of the land, part 1 & 2 (McGill University)

Hair (Thompson Rivers University)

This is not a Simple Movement part 1 & 2 (Morris and Helen Belkin Gallery)

*each of these performances took place in 2013

Over a period of one year, I dreaming and created these 3 interconnected performance art/works. I’ve had the opportunity to write about onel of them, I’ve spoken about several of them at different conferences and artist talks, and my dreams continually return to what was made through these interactions.

The dream that started these 3 interconnected performances began at the Reconciliation: Works In Progress (2012) gathering that took place at Algoma University in 2012. I was invited to speak on a panel with Roy Miki and Paulette Reagan. I loved Roy Miki. I read his poems. I learned about his work in the Redress movement in Canada. I read writing. He was one of my teachers/elders, and I had never met him before. All of the conference conversations happened in a circle. For three days, we could all see each other’s eyes. This was different. This was new. This was transformative. On that first day, my contributions to the conversation focused on my work with Indigenous children in the care of the Ministry of Children and Family Services. I was especially focused on how to support family reunification for these kids and their families; and everyday in this job I was thinking about the legacies of the Indian Residential School and how those histories are deeply interconnected with child welfare in Canada. One that first day, I offered reminders about the work of Indigenous artists and Indigenous art/history. I know I said this – I’m going to make the regalia that acknowledges our collective survival of the Indian Residentical School system. I know that I said this also: I’m going to make this regalia and I’m going to burn it so that the kids who didn’t survive those schools would have something to dance in if they needed/wanted to dance. I said this in front of Roy Miki. He didn’t know he had become my elder. My mom, Janell, taught me to always tell the truth to Elders, and because I said this in front of Roy, I had to make this regalia, and I had to burn this art/regalia as a transformative offering for the kids who didn’t make it home and might need art/regalia to dance in/with. Performance art is risky. Over these years, I’ve learned that it takes a community to make a performance art/work happen. There are also these deep and rich histories of Indigenous performance/art that are deeply rooted in much of these territories now known as Canada. It’s also important, at this point, to acknowledge the fluid sophistication of Indigenous knowledge systems, and that Indigenous performance art brings together multiple Indigenous bodies, along with their respective bodies of Indigenous knowledge, to collaborate on building beautiful unimagined possibilities.

I want to admit here: that this was a difficult essay to write.

This essay starts with the acknowledgement that I am only one of the performing bodies in these 3 interconnected performance artworks. Each one of these performances was built in collaboration with the living and physical spirits of active collaborators also known as Drums, Rattles, Mask, Button Blanket, and Eagle Fan. My oversight about not properly acknowledging these collaborators has caused me some amount of pain. I’ve realized that this oversight has left a deep hole in my understanding the work. Most people don’t know about how these performance/art/works are connected and most people don’t know why I undertook this series of durational performance/art/works. I’ve written about part one of this series in Arts of Engagement: Taking Aesthetic Action in and Beyond Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation (2016). In this previous piece of writing, I focused on acknowledging my human collaborators – Ayumi Goto, Laura Hynds, Rande Cooke, Gordy Bear, Brianna Dick, Doug Jarvis, Barry Sam, David Melville, Robin Brass, Ashok Mathur, France Trépanier, Dylan Robinson, David Garneau, Elizabeth Kalfriesh, Beverly Diamond, Sam Mckegney, Bryan Dueck – and how through performance art we turned ourselves into Ancestors. For this specific piece of writing, I focus on the intention of making a mask that honours our survival beyond the Indian Residential School System. I offer these words, and these reflections, as medicine to my unnamed and unacknowledged collaborators – Drums, Rattles, Mask, Button Blanket, Eagle Fan, and Fire. These interconnected performances: This is what happens when you perform the memory of the land part 1 & 2, Hair, and This is not a Simple Movement part 1 & 2 could not have happened without their energies/offerings/love.

This acknowledgment also turns towards Indigenous knowledge systems and the creation-acts that enable and activate the continuum of our Indigenous Knowledge systems. I can’t remember the full name of the Nisga’a Elder who first told me about the living spirits now known as Totem Poles. His first name was Larry. He was also a language warrior fighting for the revival of our respective Indigenous language(s). We were waiting to go to lunch when he shared this story with a group of us. I won’t go into depth concerning the details of the story he shared that day. I will share that his words have always stayed with me and have contributed to my pedagogical and artistic work. The part of the story that is the most relevant to this essay is: the tree called back to the carver. This reflection honours the alive spirit of the materials that make the artwork. This acknowledgment of the alive spirit of the artwork is practiced across many Indigenous Nations. This reflection honours that the artwork has a job in our cultural/intellectual/spiritual epistemological matrix. Basically, Indigenous artwork and the Indigenous artist who makes that object need each other to help build our collective survival; collective survival also includes intellectual and philosophical knowledge(s) that inform the creation of that art/work. In the 15 years that I’ve had to consider Larry’s story/gift, I’ve learned to honour how alive my artistic tools are. I’ve also learned that this aliveness, along with the act of art-making, is instrumental to the continuum of Indigenous knowledge(s).

These creative strategies, and aesthetic possibilities/traditions, become a place for building future Artists, future Ancestors, and future carriers of these acquired knowledge(s). I’m also using the phrase Indigenous Performance Art. I realize that there are several complications with putting these two ideas/practices/histories/positionalities together, Indigenous and Performance Art. Perhaps in this formation, along with being embedded within this personal reflection, these words offer a chance to expand our reliance on previous tools/structures for understanding art production in these territories now known as Canada. For the purposes of this essay, this formation offers a chance to be fluid because we are reframing our relationship to these particular ‘art/histories’ and this allows for a deeper consideration of the lived experience of the Indigenous tools that are activated, with purpose, during Indigenous performance art. These considerations become instrumental in the contemplations of Performance Art, Indigenous Performance Art, and the languages available to us that promote awareness and understanding of Indigenous Artistic production.

I’m being careful here because I don’t want any of us to be weighed down by centering Western/European art history/thinking. While Indigenous Artists continue to return, deepen, and develop our current and inherited artistic skill sets, skills developed initially by our Ancestor artists, it’s been useful for me to consider what the English words are trying to do when describing the work of performance artists, and Indigenous performance artists. It goes without saying that Indigenous artistic production can still suffer underneath the weight of Western/European art systems’ expectations, especially when we remember/acknowledge/come to terms with all of the Canadian Government’s interferences/attacks within our Indigenous world(s). Indigenous Performance Art brings bodies closer into a shared visible and experiential moment. Performance Art, and Indigenous Performance Art, reminds us that we must push ourselves beyond the learned, and inherited, Western/European walls that push our understanding(s) of body, power, and transformation in the wrong direction. Indigenous Performance Art is built around collaboration of artists with artistic tools. These tools are built and become alive and active; and they want to be alive and active with us with shared purpose. The tools want to work with us. They have goals within the artistic process. This awareness stretches how we understand/experience the resultant artwork, especially when we come to realize that artwork is alive also. It’s also good to remember that Performance Art/History, and Indigenous Performance Art/History are two separate things that speak with each other and can choose to collaborate with each other. As an inheritor of Indigenous Performance Art, I know that this has been an established artistic practice, on these territories, for thousands of years.

As I mentioned previously the goal of this series of interconnected performances was to make a useful set of Regalia, or Ceremonial Gear, for the children who died or were murdered at the Indian Residential Schools in Canada. In the first performance, we helped a carved mask come alive, and in the last performance we placed that very alive mask into the fire. In the last performance, we helped a button blanket come alive, and, along with the mask, we placed that very alive button blanket into the fire. We put these artworks/tools for creation into the fire because the fire would remake these artworks/tools and place them in the hands of our relations who died at, or were murdered by, the Indian Residential School system. Fire is the last unacknowledged collaborator here.

At this point, I turn towards Mvskoke Creek poet Joy Harjo, who in her recent book titled Why I write, offers these guiding words for the folks who follow this type of path with us., She writes:

Because of the violent interference of aggressive settlers who took over our lands in a relatively short time, we appear to be culturally gutted. When sacred places cannot be maintained, we wander. The sacredness is put away until the songs can be heard again, in the right order, and when the precise unfolding of time is most nourishing. We continue to carry these places and possibilities in our songs, our poetry, and our instructions. Our imaginations are ripe with teachings, with love and respect for those ancestors who knew and still know the particulars of how to be human. (49)

It is also important to consider Audre Lorde’s reminder about the master’s tools (1976):

For the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us to temporarily beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change. And this fact is only threatening to those women who still define the master’s house as their only source of support. (42)

And this, a reminder from the same 1976 Audre Lorde speech for consideration:

Within the interdependence of mutual (nondominant) difference lies that security which enables us to descend into the chaos of knowledge and return with true vision of our future, along with the concomitant power to effect those changes which bring that future into being. Difference is that raw and powerful connection from which our personal power is forged. (41)

These considerations become instrumental in the larger contemplations of Indigenous Performance Art, the languages available that promote awareness, and understanding of Indigenous artistic production. Some of us, Indigenous and Non-Indigenous, have never held a drum or a rattle or a mask or a button blanket before and the result of this means we come to these stories of Indigenous Performance Art with a limited imagination of the artist tools, and probably no awareness of how these tools are making creative choices within the production of the artwork. This acknowledgment isn’t about assigning a fault. This acknowledgement is focused on our collective experience of colonialism in Canada and how Canada benefits from telling a one-sided story that prioritizes itself. This limitation affects our ability to come in closer to what the Indigenous performance artist is achieving within their artwork.

A short note about the phrase come in closer: I’ve spent over 20 years developing art and pedagogy that focused on decolonizing methodologies. In my recent graduate class called “Indigenous and Decolonizing Methodologies” at OCADU, I turned my focus away from centering decolonizing methods specifically, and moved towards amplifying Indigenous power. This turning of pedagogical tools acknowledges the creative agency of our human bodies, and in practice opened a space for consideration(s) of meaning in the physical space(s) in between Indigenous knowledge/practice and Western European knowledge systems. Becoming a human being within these colonial systems continues to be a complicated mix of collective poor imagination, fear of our personal power within a capitalist system, and unlimited potential. The consideration of Indigenous artistic tools and what they are able to accomplish as alive with agency during an artistic act requires an awareness, or even an inkling, of unimagined possibilities. Western/European culture might use the word ‘chance’ here instead of ‘unimagined possibilities’. Their type of ‘chance’ is actually frozen and has a tendency to undermine the transformation power of a creative act/action. A shift away from these oppressive systems and a turn towards amplifying Indigenous power and being open to coming in closer to unimagined possibility. This is the start of ‘coming in closer’ and realizing how much Indigenous power is/has affected your current living/being. A large part of Indigenous experience is informed by Indigenous artistic tools. Audre Lorde’s clear words about the limitations of the master’s tools, and how the use of those particular tools won’t be able to shift the dynamics of power within Western/European system, does open up a space for us to imagine how Ancestor artists used tools to build future(s) for our collective bodies. Its also nice to imagine those artists and their dreaming/building of a tool that is an active contributor to making an artwork come alive for future generations.

Here I turn towards an offering shared with me by Mi’kmaq Elder artist and thinker, Peter Claire. We were visiting with Peter and Shirley at their home. I was sharing about them about my recent performance Singing Home (2015). This performance took place in Sydney Harbour, (Nova Scotia). At the beginning of the performance, I sang a song to honour the spirit of the salmon stolen away from these shores; afterwards I put on my time travelling gear, time travelled to the moment that early colonizer wooden ships arrived at that particular shoreline and proceeded to throw 150 stones at those wooden ships. Peter listened to my sharing, and reflected on what I shared by asking me, what would your Ancestors have made if there wasn’t any colonization?

I want to admit here: what a scary, and beautiful, question.

Developing new strategies for acknowledging the real lived lives of Indigenous artistic tools for the viewers of Indigenous Performance Art:

For me, this starts with the place where the two rivers meet.

I am connected to territory that is shaped by the meeting of the Stikine and Tahltan rivers.

The river is not a highway like so many anthropologists might suggest.

The river is not the land.

This starts by acknowledging the performance kinships between the physical performing bodies and the performance art tools emerges because performances art/works are relational/shared and fluid works.

We need to do this visioning before I can invite you to hold any of the artistic tools, conceptually, that helped to create these experience(s).

We need to do this so that the drums/rattles/masks/button blankets/eagle fan/fire will know that you can see them, I mean actually see them. These alive tools need to know how to trust you. You need to learn how to trust them, and talk with them.

Remember that Indigenous Performance Art is like a river in the Indigenous Art World, and the river moves through very old pathways.

Land becomes a fluid alongside the river’s movement.

Stó:lō scholar Dylan Robinson in his book Hungry Listening (2020) offers:

To experiment with different forms of writing resonant theory that consider intersubjectivity between listen, music and space and reach beyond adjectival reliance, I engage in what I call apposite methodology. Apposite methodologies are processes for conveying experience alongside subjectivity and alterity; they are forms of what is somethings referred to as “writing with” a subject in contrast to “writing about.” They also envision possibilities for how writing might not just take the form of words inscribed on the page but also forms that share space alongside or move in relationship with another subjectivity. “Writing” in this sense might be considered either a textual or material form: song writing, sculptural writing, and film writing. At the heart of these experiments in resonant theory are anticolonial epistemes for sharing experience, that emerge out of the history of performative writing. (81)

Tahltan Elder Artist Dempsey Bob shares with us, in his recent book Dempsey Bob: In His Own Voice (2022):

One Sunday morning I was just sitting, having coffee, and he just came to me. I thought, who’s going to know in the future? There was this guy called “the smart one”. I thought I better carve him. (109)

Dylan and Dempsey’s words, and books, are good reminders about how we must work to build our collective futures. I would add that their words also offer some guidance about standing in the river to develop/expand our experience(s) of Indigenous knowledge/practice/production through the matrix of performance art. You must reimagine the start, and you must reimagine the result. Dempsey’s words also bring to the front of our collective minds, the importance of risk(s) that artists must take. It is an artist that takes on the role of making the first, and sometimes, only version.

A short acknowledgement of the human contributions to:

At the start of this essay, I wrote about how I missed acknowledging all of my collaborators, within a series of interconnected performances that took place in 2013. Over the 3 performances art/works, these humans contributed to 8 hours of being present to these physical acts. Some of these humans, the ones who contributed carving and rattle-making, spent countless hours in preparation, dreaming, and making before these 8 performance hours even started.

This is what happens when you perform the memory of the land (part 1 and part 2)

Featured offerings from: Brianna Bear, Gordy Bear, Doug Jarvis, David Melville, Robin Brass, France Trépainer, Rande Cooke, Barry Sam, Laura Hynds, Valerie Hawkins, Ayumi Goto, Keavy Martin, Dylan Robinson, David Garneau, Helen Gilbert, Sam Mckegney, Beverly Diamond, Elizbeth Kalfrisch, Byron Dueck, Ashok Mathur, Skawennati, and Kyoko Goto. Also, for this performance art work, I included rattles that were gifted to me from some of the incredibly powerful Indigenous kids that I worked with while I was working as a Roots worker for Surrounded by Cedar Child and Family Services.

Hair (in collaboration between with Ayumi Goto)

Featuring offerings from Cheryl L’Hirondelle, David Garneau, Ashok Mathur, Keavy Martin, Adrian Stimpson, Jaimie Isaac, Tania Willard, and Alison Mitchel.

*There were two performance sketches that happened before the Hair performance. These performance sketches added spiritual energy and grounding towards Hair. It’s important to acknowledge both of those performance sketches: Singing to Drums and Land Drumming. These performances included offerings from: Clement Yeh, Adrian Stimson, Leah Decter, Ayumi Goto, Mimi Gellmen, Ashok Mathur, Gabe L’Hirondelle Hill, Tania Willard, Greg Young-in, Cheryl L’Hirondelle, Keavy Martin, and David Garneau.

This is not a simple movement (part 1 and part 2)

Featured offerings from: Bo Yeung, Cecily Nicholson, Lisa Ravensburgen, Corrina Sparrow, Gerry Ambers, Juliane Okot Bitek, Ayumi Goto, Ashok Mathur, Karen Duffek, Dana Claxton, Grandma Dinah Creyke, Mary Lux, and these two young children who volunteered to help me with handing out envelopes during part 2, and the 75 witnessing bodies who carried, and placed, spawning salmon envelopes into the fire with us.

Acknowledgement of the artistic tools created for these performances, and who made contributions to:

This is what happens when you perform the memory of the land (part 1 and part 2):

Two button blankets with braided hair, one button blanket with no crest design culture gun carved by Barry Sam

7 rattles made by Laura Hynds, rattles made and gifted to me by Indigenous kids who I worked with who were in foster care,

two drums covered in red earth paint,

a mask covered in horse hair carved by Rande Cook,

a song shared by Robin Brass,

and 3 Object offerings that were included from Ayumi Goto to part 1 of this performance:

Jibun, Obe, Geta.

Hair (in collaboration with Ayumi Goto)

7 picking-up the piece’s drums made from elk/deer/moose,

28 stones found on the campus while walking from the artist residence to the studio at Thompson River University

and

object offerings from Ayumi:

a wooden box painted in black and gold, wrapped in Japanese paper and filled with her washed and cut off hair.

This is not a simple movement (part 1 and part 2)

The hair-cut-off mask carved by Rande Cook,

cedar boughs collected from cedar trees around the gallery,

a button blanket covered in human hair and mother of pearl buttons,

culture gun carved by Barry Sam,

eagle fan beaded by Judy Elk,

100 spawning salmon hand-printed envelopes,

and tobacco.

It is at this point; I turn towards Joy Harjo and her words in Catching the Light (2022). She writes, “the root languages of the Western Hemisphere are Indigenous languages. These languages carry in them the plants of the area, star maps and meaning, directions concerning danger and safety, the how and meaning of becoming” (9). These words are a reminder to take care of you and me.

I want to return to the river here (for a moment). This fluid nature of the river enables the unimagined possibility for us (collectively), and will help us to make a space for how these more than human contributors (artistic tools made to contribute to Indigenous performance/art) speak/perform meaning within the production of experience that happens when these artistic tools are activated within Indigenous Performance Art. The river has different rules for determining meaning, and these rules do not centre the human. There is river time. The river’s edge creates new worlds. The river remembers back to the beginning of human time, and beyond human time. You are not standing in the river. The river subsumes you, and your human-ness, and the river adds this energy into its knowledge production cycle. I may not have an answer to Peter Claire’s question about the continuum of artistic production by Tahltan Ancestor artists, but I do have the example of how the river creates without giving away too much intellectually, and physically, to resource extraction. These objects speak more than human language, they speak and perform meaning. Our human ability limits all the ways that these alive tools are offering ways to be more expansive. As a strategy for including the more-than-human words, here, I turn to performance art as a research methodology. I take a red cloth. I tie this cloth around my eyes. I take a second red cloth and tie around my mouth. I activate my muscle memory of holding the mask and the button blanket. I ask the mask and the button blanket to contribute to this essay, acknowledging how limited human words are.

I want to admit here: I’m not going to try and interpret these words for you. I AM going to stand in the river of meaning offered by these creative offerings from these more-than-human artistic, and very alive tools.

Mask:

Warm face touching my skin

One dance

One sadness I hear this little light of mine

Warm tears touching my skin

I hear them

I hear them because there aren’t multiple worlds for me

There is only one world

I see them reaching their hands towards me

I will go to them and dance when they need to dance

These don’t have to be secret ceremonies now

Button Blanket:

Ha jump ha jump ha jump ha jump ha jump ha jump ha jump ha jump ha jump ha jump ha jump

ha jump ha jump ha jump ha jump ha jump ha jump ha jump ha jump ha jump ha jump ha jump

Ha jump ha jump ha jump ha jump ha jump ha jump ha jump ha jump ha jump ha jump ha jump

I want you to jump

I want you to jump

I want you to jump

I want to jump with you

I want to jump with you

I want jump with you

I don’t want you to cry

I want you to jump up

I want you to jump away

I want you to feel the pain fall away

I want to admit here: In writing this, I’ve also come to realize that fire is also an unnamed and unacknowledged collaborator. The Moon was an unnamed and unacknowledged collaborator. The territories that grounded these performances – Tiohtià:ke, Musequem, Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc, have also remained unacknowledged as collaborators until now.

To end, I dream the ghost hands of our relations, the ones who didn’t return or were murdered at the Indian Residential Schools, holding these objects in their hands. I dream that they are dancing and singing. This helps.

I put tobacco on the land on behalf of all of us standing in the river acknowledging the aliveness of these artistic tools and their contributions to the creation of this Indigenous Performance Art.

Bibliography

Bob, Dempsey. Dempsey Bob: in his own voice. Exhibition publication. Whistler: Audain Art Museum, 2022.

Gay, Roxanne Ed. The selected works of Audre Lorde. New York City: WW Norton Company, 2020

Harjo, Joy. Catching the light, the 2021 Windham – Campbell lecture. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2022.

Robinson, Dylan. Hungry Listening: Resonant Theory for Indigenous Sound Studies. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press,. 2020.

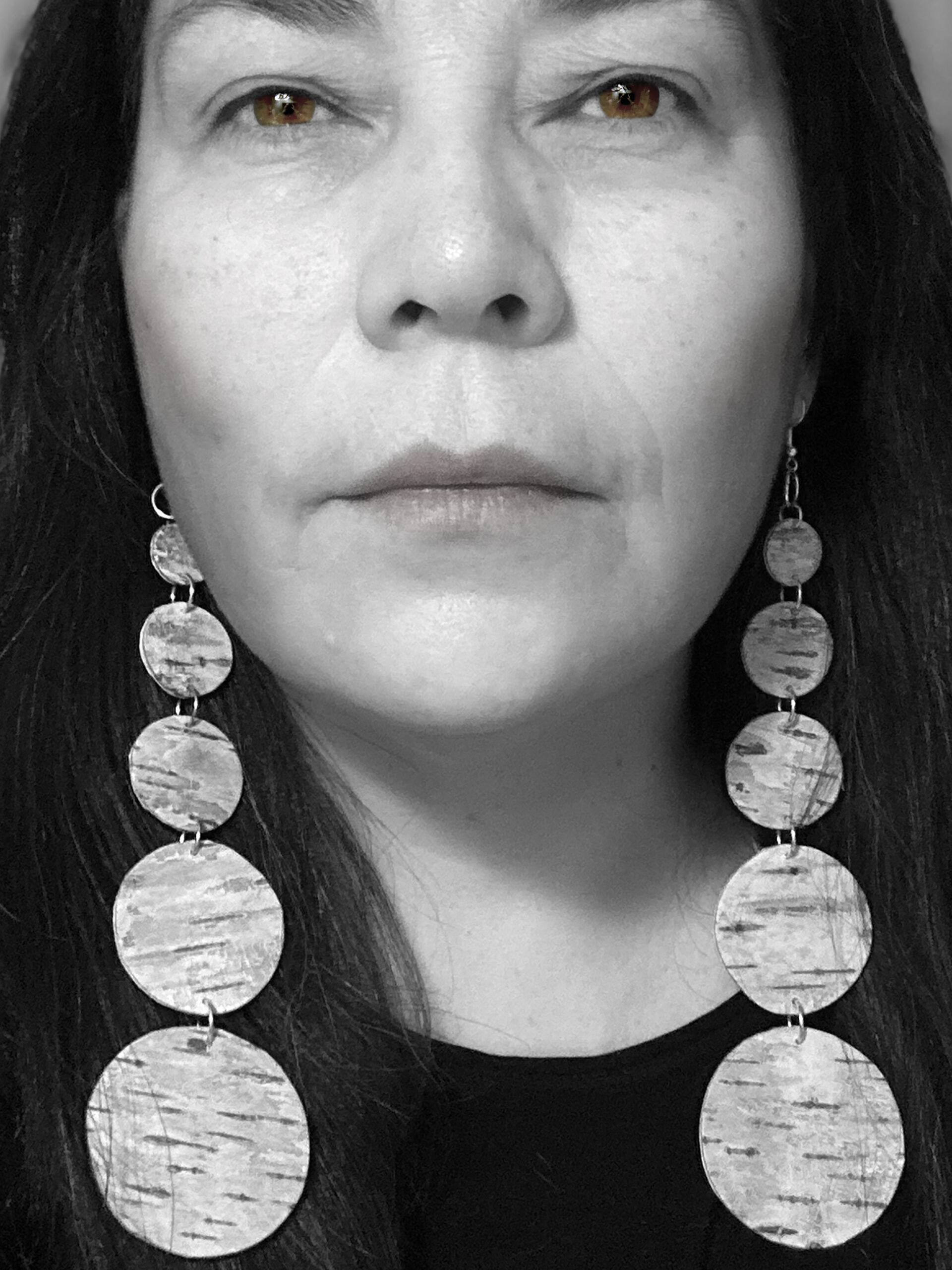

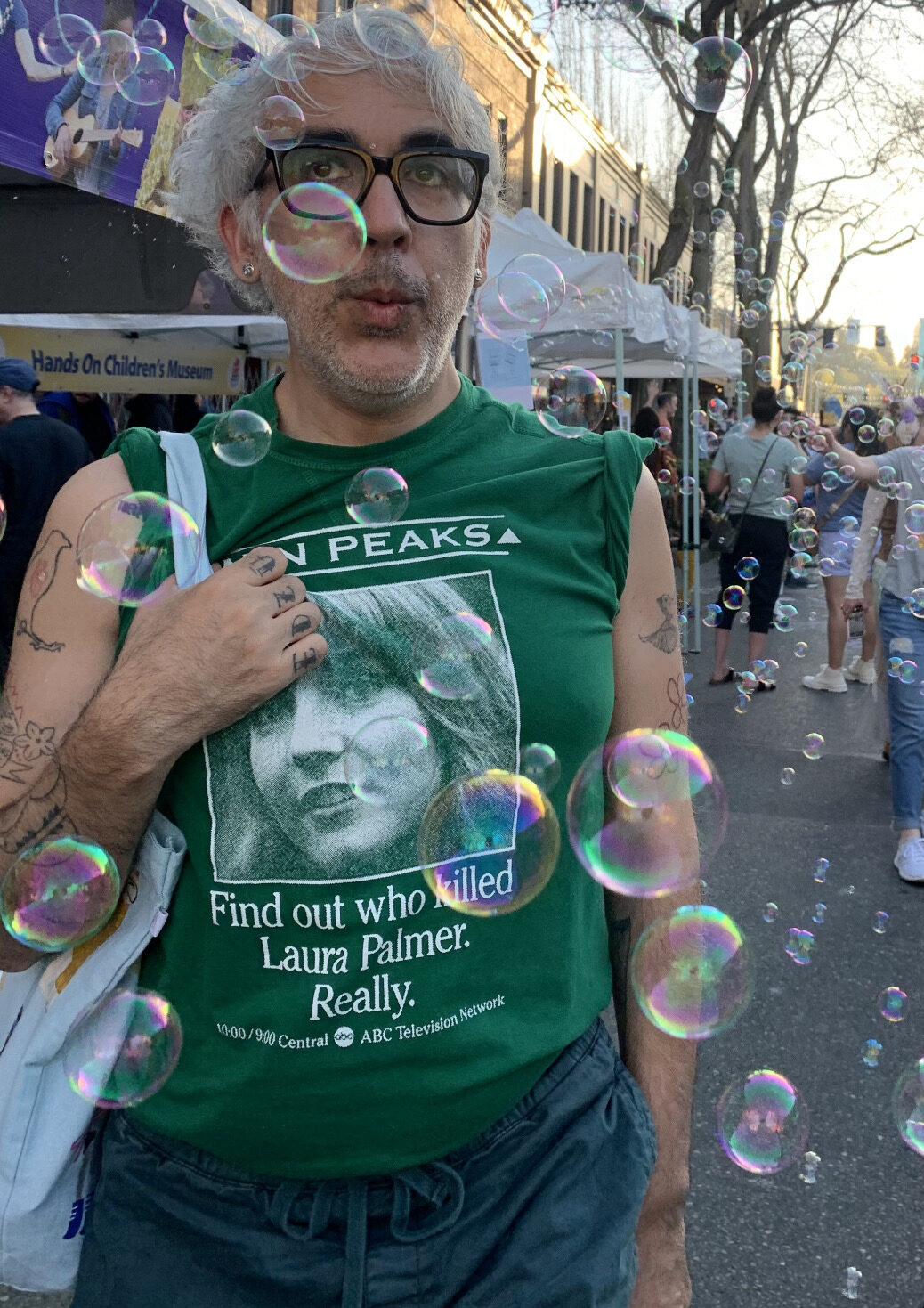

Peter Morin is a grandson of Tahltan Ancestor Artists. Morin’s artistic offerings can be organized around four themes: articulating Land/Knowing, articulating Indigenous Grief/Loss, articulating Community Knowing, and understanding the Creative Agency/Power of the Indigenous body. The work takes place in galleries, in community, in collaboration, and on the land. All of the work is informed by dreams, Ancestors, Family members, and Performance Art as a Research Methodology. Initially trained in lithography, Morin’s artistic practice moves from Printmaking to Poetry to Beadwork to Installation to Drum Making to Performance Art. Peter is the son of Janelle Creyke (Crow Clan, Tahltan Nation) and Pierre Morin (French-Canadian). Throughout his exhibition and making history, Morin has focused upon his matrilineal inheritances in homage to the matriarchal structuring of the Tahltan Nation, and prioritizes Cross-Ancestral collaborations. Morin was longlisted for the Brink Award (2013) and the Sobey Art Award in 2014/2023, respectively. In 2016, Morin received the Hnatyshyn Foundation Award for Outstanding Achievement by a Canadian Mid-Career Artist. Peter Morin currently holds a tenured appointment in the Faculty of Arts at the Ontario College of Art and Design University in Toronto.

Peter Morin is a grandson of Tahltan Ancestor Artists. Morin’s artistic offerings can be organized around four themes: articulating Land/Knowing, articulating Indigenous Grief/Loss, articulating Community Knowing, and understanding the Creative Agency/Power of the Indigenous body. The work takes place in galleries, in community, in collaboration, and on the land. All of the work is informed by dreams, Ancestors, Family members, and Performance Art as a Research Methodology. Initially trained in lithography, Morin’s artistic practice moves from Printmaking to Poetry to Beadwork to Installation to Drum Making to Performance Art. Peter is the son of Janelle Creyke (Crow Clan, Tahltan Nation) and Pierre Morin (French-Canadian). Throughout his exhibition and making history, Morin has focused upon his matrilineal inheritances in homage to the matriarchal structuring of the Tahltan Nation, and prioritizes Cross-Ancestral collaborations. Morin was longlisted for the Brink Award (2013) and the Sobey Art Award in 2014/2023, respectively. In 2016, Morin received the Hnatyshyn Foundation Award for Outstanding Achievement by a Canadian Mid-Career Artist. Peter Morin currently holds a tenured appointment in the Faculty of Arts at the Ontario College of Art and Design University in Toronto.