Representing “The Indigenous Experience”

Cousins and Kin Program at DOXA 2021

By Evelyn Pakinewatik

Cousins and Kin Program

Curated by the Cousin Collective

DOXA Documentary Film Festival

Vancouver, BC

May 6-16, 2021

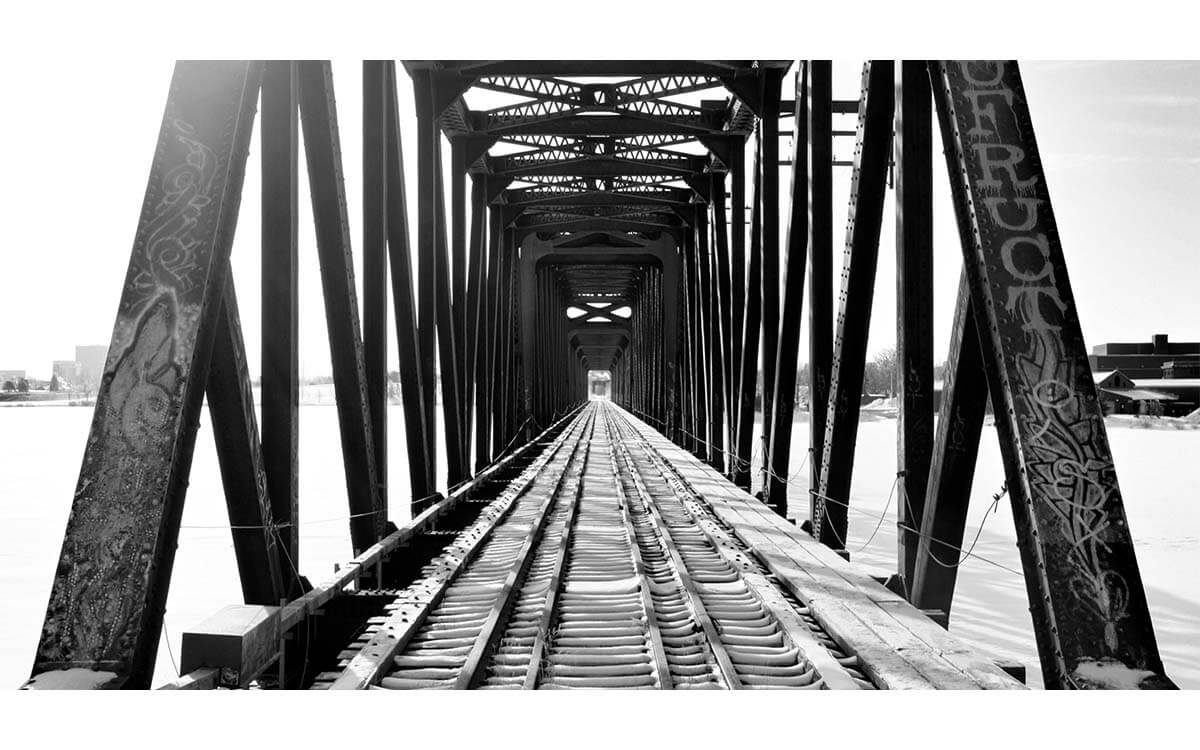

“Extinct” isn’t the right word, but I don’t know how else to describe the constant moral quandary of trying to function ethically in this world as it’s ending. If I grow my own food, and build my own house, and sew my own clothes, if I take shovel and nail and needle and axe, who mined the metal I would then hold in my hands? What spirit and memory lives within my camera before I ever hold it to my eye? This question is as strange as it is heavy, and it is this weight which reminds me that filmmaking is a privilege afforded to a few. Someone is paying for it. I don’t always know who.

I can’t help but think of the somber black-and-white portraits of the miners of Potosí in Miguel Hilari’s Bocamina. Potosí is a colonial Bolivian mining town in the shadow of a great mountain whose children will inevitably join their fathers to work in the dark of the earth.

In Colectivo Los Ingrávidos’ Impressions for a Sound and Light Machine, an unseen woman declares, trancelike, “Here they come, the dead, so lonely, so silent, so ours…”

I will likely never know her, but I can hear her, still. I can feel her. Cut and cut away the image, until all that’s left is light! “…with a bowl of horrors between their hands, their terrifying tenderness…”

Colectivo Los Ingrávidos portrays grief with a hard slash through celluloid. James Luna’s The History of the Luiseño People depicts grief as a Charlie Brown Christmas tree with a beer can topper and sunglasses worn indoors.

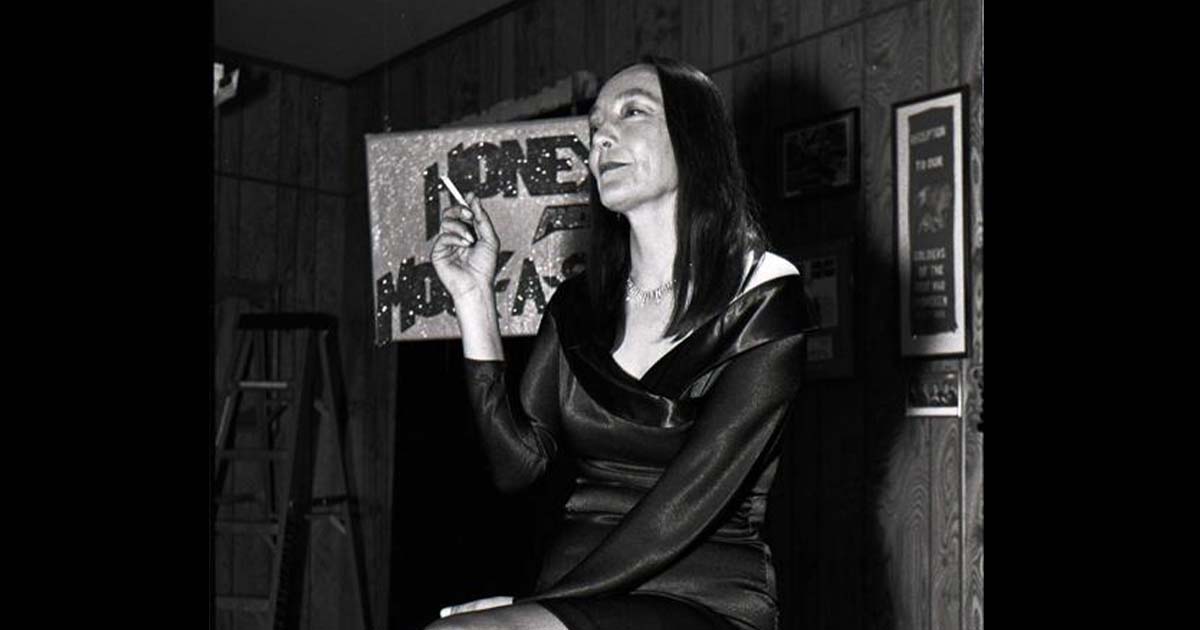

In Shelley Niro’s Honey Moccasin, Zachary John shifts uncomfortably in his seat, saying, “It’s okay stuff, I guess. But a little on the weird side – it’s just too heavy! It’s supposed to be a night out for enjoyment, fun. Time to forget about your problems, not have somebody remind you over and over again about this depressing stuff. Drink, dance, be merry!” The man beside him silently turns away. Without too much thought, Zachary takes the opportunity to swipe his neighbor’s beaded sheath left sitting on the table, tucking it away into the sleeve of his jacket.

It’s an all-too-familiar complaint; – Lighten up! – Get over it! You meet people who are In It, who Fight It, who Ignore It when they can, and Deny It when they can’t. The Indigenous Experience, so often experienced as various degrees of disconnect and dissociation. It is hard to say, even in celebration, what we can do that is not in some way a response to colonization.

The titular Honey Moccasin spins and transforms Lynda Carter-style into Detective Honey Moccasin with deerstalker hat and unrelenting poise. She’s in a band! She owns a bar! She has a daughter in film school! She’s here to solve the mystery and bring the culprit to (non-carceral) justice. Most importantly, Honey Moccasin makes us smile. Indians get to have fun too, even when you talk about the “depressing stuff.”

A few years ago, I listened to Sky Hopinka talk in Maine where he asked the question, “Am I Native person with a camera, or a camera person who happens to be Native?” It was also in Maine when I first held a whole lobster in my hands. I was one of those children who stopped at grocery store lobster tanks if I saw them, just to visit. Lobsters know what many don’t – Hell is real, and only we have the power to condemn them. Caroline Monnet’s Creatura Dada represents a feast of lobster, oyster, and champagne in grotesque and gorgeous celebration. Look at our beauty and our splendor, those feasting and watching us seem to say. They are all Indigenous women, and this feast, this celebration, is their Indigenous Experience. My Maine lobster, like those in Creatura Dada, was shiny and red and I wept as I ate it. I have never seen or held a creature more beautiful.

There’s more to say, but if I said it all, I’d never stop talking. Cousins and Kin does not satisfy, and does not attempt to satisfy, the expectation of a non-Indigenous audience. I can’t tell you how much of a relief that is.

Acknowledgement: This article (Representing “The Indigenous Experience”) was originally written as part of the partnership between ICCA and Rungh Magazine. As part of our long-term collaboration, ICCA offers writing opportunities for our community members while highlighting BIPOC exhibitions and programming in Rungh. Rungh Vol. 9, No. 2

Evelyn Pakinewatik (Nbisiing Anishnaabe/Irish, Nipissing First Nation) is a filmmaker and multidisciplinary artist. Evelyn’s work explores the intersection of dreams and memory and the societal distortions of interiority, relationality, and animacy.

An artist raised by artists, Evelyn began working alongside their parents from a very young age to preserve and disseminate traditional textile and nature arts in Indigenous communities across Ontario and Québec. Interconnectivity and reciprocity continue to motivate Evelyn’s creative process as they seek to practice anti-colonial survivance through an inclusive lens.

Evelyn is a 2018 Reelworld E20 Fellow, 2019 4th World Media Lab Fellow, a 2020 HotDocs Doc Accelerator Fellow, and a 2021 EFM Doc Salon Fellow. Evelyn’s films have been screened at various festivals including the imagineNATIVE Film and Media Arts Festival, LA Skins Fest, St. John’s International Women’s Film Festival, Māoriland Film Festival, Festival Présence Autochtone, and the Toronto Queer Film Festival. Their work has also been exhibited at the Ojibwe Cultural Foundation, Toronto City Hall, and the Bentway at Fort York. Evelyn has been invited to speak at higher learning institutions including the Ontario College of Art and Design University and Cornell University. They have received generous support from the Ontario Arts Council, the Canada Council for the Arts, and the Indigenous Screen Office.

Evelyn’s recent projects include “Nooj Goji/Anywhere” (2024), a short film which explores immunocompromised identity within an Anishinaabe context, and “Abiinoojiikaasmin”(2025), a short film centring the voices and futures of Indigenous children. Upcoming projects include a documentary series with the National Film Board of Canada.