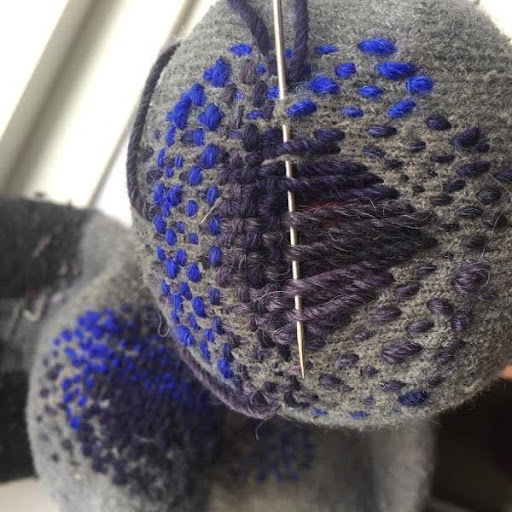

[Fig. 1: Unplanned opening in the fabric of a knitted sock.]

#DevirtuousMends

By Keavy Martin

Holes: they are in fact essential to clothing. Without holes for legs, arms, heads, and torsos, our garments would be unusable, inaccessible, closed systems with which we could not interact (Hákonardóttir 25). Our bodies, likewise, require holes to function and to remain in co-being with the world. Holes like the one pictured above [Fig. 1], however—worn into fabric through accident or repeated wear—mean something else to many of us. Wound-like, they signal a problem, and perhaps not only that the garment is now injured and thus restricted in its usefulness, less comfortable, or beginning its process of decay; rather, they also seem to bring shame upon us, these unruly, unplanned holes, as if evidence, a manifestation, of some internal flaw.

In 1944, the Simes Report, written for the Department of Indian Affairs to assess the state of Elkhorn Residential School in Manitoba, “added deplorable clothes and shoes to the list of everything else at the school that was wholly ‘unsatisfactory. [The children’s] clothes were disgraceful. The clothing was not only dirty but torn and ragged. Their stockings were full of holes’” (qtd. in Milloy 126, emphasis added). The report, intended to convey alarm about the state of affairs at Elkhorn school—in essence, to provoke into remedial action both the school administrators and the Department—nonetheless shames the students for their appearance, which is a source of concern at a moment when the clothing of children incarcerated in Indian residential schools is expected to perform both a moral and communicative function: to enact and also to signal their transformation. The children’s clothes, as John Milloy notes, “were to be the first outward sign of what was assumed would soon be the inner grace of civilization” (124). Simes’s concern about holes in the children’s clothing, then, was perhaps not so much about their comfort and wellbeing: it was about the perceived degradation of the children’s image—and therefore, of the image of those who had taken it upon themselves to ‘fix’ them.

The impulse to ‘fix’ others who are imagined to be defective is, of course, a core and ongoing settler colonial strategy. While the fundamental goal of colonial projects may be control over lands and resources (also presumed deficient in their apparent ‘idleness’[1]), the rhetorical construction of others who are flawed and in need of correction provides the central and deeply racist ‘justification’ for what would otherwise be morally inexcusable: the theft of another’s lands. Daniel Heath Justice, in Why Indigenous Literatures Matter, notes the ways in which “the colonial imaginary is predicated on a fiction of Indigenous deficiency and absence, an empty frontier awaiting white supremacy to give it shape and substance…” (152). This is the sort of fiction that allowed Duncan Campbell Scott, in 1920, to declare before the House of Commons, “I want to get rid of the Indian problem,” while proposing compulsory education in Indian residential and day schools as the method (qtd. in Wakeham and Henderson, Reconciling 312). Imagined absences and flaws: these are the rhetorical foils against which white subjectivity in Canada has produced its own sense of validity and justified its seizure of Indigenous lands. Colonial takeover is rendered, then, as service, as a benevolent gift, as a kindness, as the virtuous mending of holes.

I rehash these well-known rhetorical atrocities in order to raise the problem that prompts this inquiry: that in an age where white Canadian society is purportedly attempting to make amends for its colonial wrongs, it continues to rely on many of the same metaphors (mending, repair) and the same relational structures (supposed kindness, generosity, good intentions, service, sacrifice, goodwill, etc.). Here, I follow Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, who notes that

…what is really crystal clear to me is that these gifts of reconciliation, whether they’re treaties, Royal Commissions, or Inquiries, are an integral part of a much larger cycle of settler colonial violence and occupation, even though they are positioned by the state as a break in the cycle, as a way out of the cycle, as turning over a new leaf and embarking on a new relationship based on mutual respect and trust—or whatever the language of the day.

I take this potent critique as applicable not only to the reconciliatory strategies of the state but also to the everyday practices of reconciliation, the small gestures of goodwill, the sincere efforts to respond to the TRC and its Calls to Actions that now permeate institutions across the country.

In this project, then, I take up a practice of literal mending as a way to better grasp the ongoing problems of white settler-colonial amends-making. I am interested here in the potential of embodied inquiry, in what the slow and painstaking labour of darning might make plain in ways that language alone cannot. In what way is repair—the impulse to fix, to improve—a kind of reflex, a muscle memory bound to the fibres of white settler bodies, carved into synapse by generations of habit? What might a process of actual darning, of literal repair, reveal at a point when mending metaphors have become so widespread? This essay is centrally concerned with the way in which white mending—both literal and figurative—is closely associated with the production of virtue, and thus, how it works almost inevitably to benefit the white mender. The risk of virtue, of course, is imagined innocence (Mawhinney qtd. in Tuck and Yang), or purity (Shotwell): a state of exceptionalism that allows us to imagine ourselves to be distinct from those who cause harm. For as Alexis Shotwell cautions in her 2016 Against Purity, “The slate has never been clean…. There is not a pre-racial state we could access, erasing histories of slavery, forced labor on railroads, colonialism, genocide, and their concomitant responsibilities and requirements” (4). And while it’s essential to respond to calls for redress (as the Métis scholar Chelsea Vowel says, “when we tell you what we need, GIVE IT TO US”), there is likewise a need for vigilance around the desire to help, to fix, to be of service, to be kind, to do the right thing, as it can also be ultimately self-serving, aimed at the production of virtue rather than at the pursuit of justice. In an attempt to unlearn or to resist this habitual clawing after white virtue, I seek to initiate here a practice of devirtuous mending: mending that refuses an accruing of moral capital, that is useless—mending that renders visible the conceit, the troubled origins, the impossibility of mending at a time when the process of damage and destruction has not yet ceased.

[Fig. 2: Woven sock darn in process.]

To mend, to amend, to make amends. These three concepts—in English, at least—have a common origin in the Old French amender and thus in the Latin ēmendāre [“amend, v”]. As the Oxford English Dictionary explains, the prefix ē— is short for ex—, or “out” (“out of,” “from”), here added to the root “mendum,” meaning a fault. Ēmendāre: to ‘out’ a fault, in the sense of removing it. This is a word of potential but also of some danger.

To “mend” is to fix, but only in particular ways. The word brings to mind a process of repairing textiles, as in the case of a ripped seam or worn elbow. Non-textile domestic objects like cups, the toaster, or the car are less often said to require ‘mending’—more often, these things are ‘repaired’ or ‘fixed,’ if this happens to them at all. (This may reflect a North American bias, with ‘mend’ being in less common usage here than in the UK—except that we know from Robert Frost that walls and fences can also be mended.) Mending tends to refer to a broken thing that needs to be made intact—not just something that is malfunctioning. The outward motion that the Latin origin word conveys (with its ē- prefix) is a bit odd, because mending in practice tends to be less about removing something faulty and rather about inserting something—a woven patch, some lacquer, some field stones—in order to fill a gap that has developed. Mending requires a hole.

Perhaps even more common today is the usage of ‘mending’ to refer to a healing process—and here is where metaphorical uses also abound. Bones can be mended (often through another textile metaphor: knitting), and wounds can be mended as well (typically through stitching). People recovering from colds and other illnesses or injuries are said to be ‘on the mend’—and so, too, are economies, which are often personified in news headlines, with figurative periods of ailment, recovery, and health[2]. Metaphors of mending and of repair are also widely employed in political contexts—most notably during redress processes, such as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC). “By establishing a new and respectful relationship between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Canadians,” promises one TRC final report, “we will restore what must be restored, repair what must be repaired, and return what must be returned” (Truth and Reconciliation Commission, What We Have Learned 1). Repair, the middle child of this trio of re-verbs, is consistently invoked through the TRC’s communications, often with reference to the repairing of harm, the repairing of conflict, and the repairing of damaged trust. These metaphors can function as potent calls to make that vague entity known as ‘reconciliation’ more material, more concrete; ‘repair,’ after all, requires action, not just words. These are mending processes that are about the making of amends: the righting of wrongs, the filling in of gaps, the offering of something by way of compensation for what has been broken.

Mending—whether it is socks or political relationships or the rehabilitation of one’s ways—is inevitably a moral process. To “amend” is to correct, to improve: we might think of a contract or constitution—a text presumed inanimate, which will not be shamed in having to be amended. Yet the history of this term in English includes a now-obsolete transitive use in which the object being amended is a person: Charles Richardson’s 1839 English dictionary defines this verb as follows: “To free from deficiency, fault, or blemish; to repair, to correct, to improve, to reform, to recover; to correct, to chasten, or chastise” (22). The 1535 Coverdale Bible employed this term in Matthew 3:2, when John the Baptist preached in the ‘wilderness’ of Judea: “Amende youre selues the kyngdome of heuen is at honde” (“amend, v.”) “Amend yourselves”: later versions render this simply, “repent!”[3] In this usage, a human becomes the flawed object, their ‘fault’ being less a sign of wear but rather a spiritual defect, a deviance, something inherent. The amender, then, acts piously, virtuously, ridding themselves of fault, unless the verb is in the transitive mode (where the subject acts upon another object), in which case the amender functions benevolently, taking pity on the flawed, ridding others of their faults—and proposing to save them in the process.

“In 1889, the principal of the High River school, E. Claude, reported that, in the previous year, the girls at the school had produced substantial goods: 27 aprons were made; bonnets, 6; coats, 28; drawers, 25; dresses, 34; garters, 23; night-dresses, 89; mattresses 6; mitts, 14; napkins, 37; overstockings, 12; petticoats, 17; pillows, 6; sheets, 14; shirts, 80; towels, 72; trousers, 48; socks, 64; stockings, 6 (these last two articles are hand knitting);—besides the ordinary mending of theirs and the boys’ clothes.” (Truth and Reconciliation Commission, The History 333-334)

Mending, darning: these were everyday activities at Indian Residential Schools—for girls, specifically. Until the advent of cheap, mass-produced machine-knit socks, darning would have been a common activity of most women, unless they were wealthy enough to avoid it. But in institutional settings, this work had a pedagogical and moral purpose beyond utility: K. Tsianina Lomawaima writes about the ubiquity of manual labour in U.S. Federal Indian schools, wherein girls were required to spend half of their school day “sewing hundreds of shirts, darning thousands of socks, polishing miles of corridor” not only to keep the schools and their uniforms operational but also to learn obedience to those in power, a key component of the ‘transformation’ that the schools aimed to bring about in Indigenous children (230).

Needlework, in particular, seems to have performed a very particular function in the schools, thanks to the influence of Victorian ideas about the transformative and disciplining value of sewing. Katrina Paxton has written about the ways in which domestic tasks like sewing were part of “a quiet indoctrination of hundreds of young women into Protestant domestic and gender ideals” such as “purity, piety, obedience, domesticity, selflessness, sacrifice, personal cleanliness, meekness, reverence of motherhood, and dedication to family” (176, 177). Rozsika Parker, in The Subversive Stitch, analyzes the posture of an 1888 depiction of an embroiderer by the British painter Marcus Stone: “Eyes lowered, head bent, the embroiderer’s pose signifies subjugation, submission and modesty, yet her silence also suggests self-containment.” She notes that this capacity of the work of embroidery to shape women into ideal, virtuous, feminine Victorian subjects was likewise employed in the disciplining (under the guise of benevolence) of the lower classes.[4] In requiring Indigenous children to mend, school officials fantasized that they were likewise supervising a process of moral or spiritual repair: a metanoia, a change of mind, a conversion. In essence, these institutions aimed to amend Indigenous children, presuming them deficient, requiring them to be flawed—so that they could act as foils for the production of white settler-colonial benevolence.

It must be noted, however, that children in residential schools did not just passively accept these attempts to govern their bodies and souls. The literary and historical record reveals multiple accounts of their resistance: Lomawaima recounts a story of the girls at Chilocco Indian Agricultural School in Oklahoma, who cut off and donned only the legs of their required bloomers, so that a glimpse would convince the matrons that they were being worn (before being cast off shortly thereafter) (227). In Margaret Pokiak-Fenton and Christy Jordan-Fenton’s Fatty Legs (2010), the protagonist Olemaun defiantly flings her wool stockings into the fire (70), while David Robertson and Julie Flett’s 2017 children’s book When We Were Alone has a grandmother recounting the numerous ways that she and the other children cultivated subversive practices of joy while at school—covering their dull clothes with brightly coloured fall leaves and braiding long grass into their cropped hair. Later, in the post-TRC era, numerous survivors and their descendants have either taken up needles and/or re-signified textiles to testify to their experience, creating sewn responses like the Living Healing Quilt Project (organized by Alice Williams of Curve Lake First Nation), the numerous blankets offered to the TRC’s Bentwood Box, the Ribbons of Reconciliation campaign, Phyllis Webstad’s Orange Shirt Day, or the blanket mending project by the high school students at James Alternative School in Winnipeg.[5] As Celeste Pedri-Spade writes of her own Anishinabe family history, the continuation of Indigenous making practices—like sewing and beadwork—offers a rich, embodied, and relational method of engaging with historical records like photographs, with other material things, and with family memory (136). These practices attest to the possibilities of deploying textile arts outside, beyond, and against the colonial and gendered ideologies that imbued this kind of labour in residential schools.

I began mending in 2018 following a conversation with Rosa Wah-Shee, a Tłı̨chǫ residential school survivor who attended Breynat Hall and Grandin College, both Catholic-run institutions in Fort Smith, NWT, and who later worked for decades with the GNWT Department of Health and Social Services.[6] Rosa is also my mother-in-law: my husband’s mom, and our child’s grandma. (My own blood relatives are white settlers; no one in my own family, therefore, was ever taken away to residential school.) One day, as I sat at the kitchen table knitting, Rosa began to talk about having had to darn socks as a young girl at Breynat Hall. She describes being supervised by nuns as she and the other girls repaired unidentified socks by placing them over a darning mushroom and then weaving the thread back and forth, back and forth. They had to darn neatly, she said, with no loose threads. Having never darned (having never been required to darn), I listened to her describe the process of weaving in a new fabric to fill a sock’s hole, struggling to imagine what she meant, how this process worked. It later occurred to me to try it, not only for the practical reason of repair (beset, in my case, with 21st century upper-middle-class anxiety about the material impacts of my existence: specifically, the exploitative conditions of the production of the items in my closet—and their potential afterlives of slow decay in landfill); also, this practice seems to offer one way of thinking—through doing—about the problems and possibilities of repair.

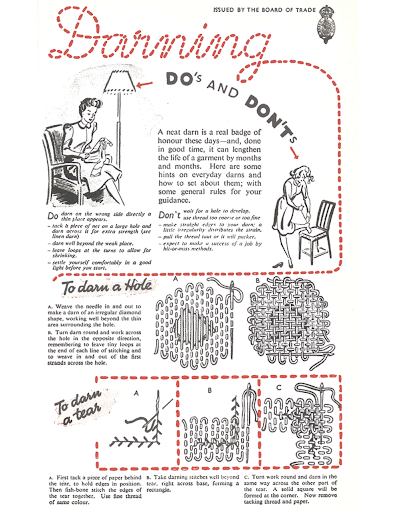

In order to learn to darn, I first work on my own holey garments. The internet has numerous videos, images and diagrams, the most useful of which are actually reproductions of a series of pamphlets produced for the British Board of Trade in the 1940s as a response to wartime clothes rationing, which was introduced on June 1st, 1941. This initiative, which popularized the slogan “Make Do and Mend” (now again in use as a social media hashtag in the mending community), contains detailed instructions about the mechanics of darning—while simultaneously imbuing these instructions with notable moral overtones.

[Fig. 3: “Darning Do’s and Dont’s” pamphlet, issued by the UK Board of Trade in 1942]

One example in the series—a poster entitled “Darning Do’s and Don’ts” begins with a promise: “A neat darn is a real badge of honour these days.” This invocation of an ideal moral state or accomplishment—and its potential recognition by others—is reflected in the illustrations that accompany the poster. At the top left, a white woman is seated, pulling a needle and thread from the heel of an overturned stocking that is tensioned perfectly over a darning mushroom. She leans forward slightly into the light—both a practical reminder about the good visibility needed for darning but also evoking a kind of benediction, a blessed state. Eyes downcast, back straight, hair pinned, mouth pressed closed, collar buttoned tight at her throat, she is a picture of pious devotion and restrained, dutiful, wifely femininity. Off on the other side, notably smaller and lower down, the antithetical figure is mangling a similar task: standing dangerously on one high-heeled leg, this woman attempts to darn a stocking that is still on her foot, which is propped awkwardly onto a chair behind her. Hair loose, brow knitted, skirt swaying, she wrestles impatiently with this chore, looking like she is about to pitch over onto the carpet. The message is clear to me, even as a 21st-century middle-class white woman never expected to sew: this person is a slattern, her stitches as loose and untidy as her morals.

With the help of these clear guidelines from my great-grandmothers’ generation, I begin to darn. I am not alone in this. Indeed, mending in the 21st century is on the upswing, with scholars and practitioners like Kate Fletcher, Tom van Deijnen [Tom of Holland], and Jonnet Middleton all drawing attention to the possibilities of repair as a means of addressing the substantial ethical problems—human rights abuses in the labour chain, appalling environmental impacts, massive waste—in the global textiles industry. I join in this international mending movement by posting photos of my work to the public Instagram page (@globe.thistle) that I created specifically for this purpose. I use hashtags like #visiblemending, #repairnotreplace, #lovedclotheslast and #makedoandmend, fingerwagging phrases that here serve to connect me to a community of other frugal, sustainably minded—and, let’s face it, virtuous—menders. I tell myself that in mending with such diligence and in such a public-facing way, I am—to borrow the words of Middleton and the futuremenders collective—working to ‘usher in the Age of Mending,’ where people raised in a time of mass consumption and waste will renew their relationships to things, honouring the materials and labour that went into their production and extending their use for years if not decades (Futuremenders).

Out in the world, I wear my mended garments and talk cheerily with coworkers and strangers about the techniques used (really very quick to learn, I assure them). I confess the pleasure that is produced—the new relationship with the garment, which is now a favourite unlike anything else, an heirloom to be treasured. My mending therefore becomes a status symbol—the “badge of honour” promised by the 1940s Board of Trade—my position in history and in society ensuring that my patches confer only admiration, my commitment to sustainability, and never danger. I can safely look shabby, even, with a deliberately frayed knee patch, without fear for my job safety, my custody of my child. My visible mending marks my privilege in addition to my virtue.

With caution, then—and with a set of reasonable repair skills—I turn to the more complex task of mending for others. I want to know what it means to mend across relationships; I want this literal mending to teach me about the possibilities and the risks of amends-making. A few people acquiesce to my strange request to darn their socks. I take up this task with all the respect, all the care, that I can muster. I wait until I am alone and things are quiet. I do not watch TV while mending. Nothing is posted to Instagram. I ensure that I have enough light. Thinking about what I have heard from beadworkers about the capacity of material things to absorb human energy, I am careful with my thoughts and feelings. I try to listen closely to the garment and how it would like to be mended, which colours it prefers. I agonize, wanting the mend to be beautiful, comfortable, but also practical (as in: able to go in the washing machine). I produce absolutely the best darns that I can. Something still feels odd about it.

Mending is not unidirectional. It has a way of disrupting the expected flow from subject to object, where I act upon the thing, rescuing it, fixing it, giving it new life, saving it from oblivion. The garment is a strong participant in this process, its construction and materials determining what kind of mending is possible. At times, it resists my efforts, the yarn or fabric refusing to cooperate. At times, it renders my work ridiculous, such as when I realize that my painstaking and beautiful visible mend on a dress will be positioned—far too visibly—directly over a part of the wearer’s body that they perhaps to not want to draw attention to. Although I think often about the resources that are required to mend—the electricity, the calories, the water that must flow through the mender and their materials—I realize too that mending is a process of consumption, a harvesting: a taking of something. The garment, the yarn, the needle: they collaborate to work upon me, directing me, soothing me. Mending fixes me, arresting me in the material world, in the task-at-hand; I am being fed by this process, maybe healed; there is a troubling pleasure in this repair work, a semblance of control over a small and easily resolved problem, the joy of gifting these small repairs back to people.

I appreciate those who tolerated me during this process of learning. I am likewise grateful to those who did not tolerate me, who refused my requests to allow me to mend for them. Their refusal—their having to refuse this strange request—teaches me two key things: a) the seeking of consent, even when a ‘no’ is respected, can still be a kind of violence, and there is still labour—unjust labour—involved in refusal, and b) that good intentions, the desire to serve, the impulse to provide care, the willingness to give gifts, even the desire to made amends—these are deeply embedded in and not the exception to settler colonialism, which often perpetuates itself not only through cruelty but also through kindness[7] (These things will already be obvious to many; this darning practice is how I came to understand them more fully.)

My contention here is that the power of mending—the problem of mending—is the virtue, the state of grace, that it bestows upon the mender. As Eva Mackey argues in the context of the 2008 apology to survivors of Indian Residential Schools (a key moment in the national amends-making process): “How is it that those who apologize… appear to emerge after the apology ritual washed clean and innocent, feeling redeemed, future-looking, and unified?” (Mackey 49). Apology, she suggests, risks serving the apologizer more than the recipient, particularly at a moment when the crimes of the state against Indigenous nations continue. These acts of mending can become a performative exceptionalism—a signaling of virtue, of exemption from complicity. Mending likewise carries this risk, for what ought to render the amends-maker penitent, contrite, and humble could potentially cast them as pure, or benevolent, selflessly bestowing improvement upon deficient things. As Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang famously say of white settler reliance on decolonization as a metaphor, it “makes possible a set of evasions, or ‘settler moves to innocence,’ that problematically attempt to reconcile settler guilt and complicity, and rescue settler futurity” (1). Can amends be made (can mends be made) without this kind of piracy, this accruing of virtue, this wresting of moral capital from the things themselves?

[Fig. 4: A sock darn left unfinished, with loose ends trailing impractically.]

As I work, I begin to wonder what happens when the threads emerging from a darn, rather than being neatly and invisibly woven back through, tucked away where they will not snag or catch, are left loose, trailing.

There is a problem of temporality in repair metaphors. In order for mending to occur, a hole (or area of wear) must have been made—but more importantly, it must have ceased being made. We are warned not ever to wear or to wash socks once they begin to show signs that a hole is forming: this, rather, is the moment for mending.[8] The object must cease in its circulation; it must be extracted from the cycle of use. There must be a moment of stasis in which the mend can occur. If wear is ongoing, if the hole is still forming, darning is difficult, if not impossible. One cannot darn socks while wearing them; or rather, one can try, but somebody is likely to get hurt, either from strain or from stabbing. Mending requires a pause, a ceasefire.

Metaphors of repair, then—when used to describe political relationships—perform a dangerous kind of work: they imply automatically that the harm has ceased—and that mending therefore is possible. Pauline Wakeham and Jennifer Henderson identified this problem early on in the moments following the 2008 federal apology to Indian residential school survivors, with its “strategic isolation and containment of residential schools as a discrete historical problem of educational malpractice rather than one devastating prong of an overarching and multifaceted system of colonial oppression that persists in the present” (“Colonial Reckoning” 2). Settler-colonial violence, in other words, is consistently imagined to be in the past, safely contained in the “sad chapter” that was the Indian residential school system.[9] This is yet another strategy of distancing, whereby contemporary liberal Canadians imagine themselves to be separate from settler-colonial violence. The reality—as myriad scholars and activists point out almost continually—is that settler colonialism is “a structure not an event” (Wolfe 388), and that the structure is still standing: Canada continues to work legally, militarily, and rhetorically to secure its control over Indigenous territories, to justify its access to resources lying within and beneath Indigenous lands, to ignore its treaty obligations, to exonerate white settlers who harm or end Indigenous lives.[10]

Despite this reality of ongoing colonialism, many of us left-leaning white people imagining ourselves to be allied with Indigenous causes continue, often unaware, to employ strategies of distancing, of rhetorical self-purification, in believing ourselves to be separate from colonial racism and violence via our intellectual opposition to it. In the wake of the TRC’s Calls to Actions, government offices, schools, and institutions (like the one at which I am employed) are now abounding with reconciliatory gestures; many of these are meaningful, having been guided and made possible by Indigenous experts (and through tremendous labour by Indigenous staff). Others are less successful, having floundered in the consultation phase, or having been deployed primarily as photo evidence of or a good news story about a benevolent institution that is swiftly becoming a ‘leader in reconciliation,’ or some such thing. My central worry is that what is continuing amidst all of this—even alongside many good initiatives—is the prioritizing of white virtue and redemption: strategies of disengagement that fail to acknowledge ongoing embeddedness, complicity, and responsibility.[12] To borrow the words of Papaschase Cree scholar Dwayne Donald, white virtue is a core component of the “ongoing process of denying relationship”[13] to larger structures of harm—and it is, therefore, inevitably a perpetuation of colonialism.

I have come to understand that the problem of white virtue-extraction is one that I cannot only think or read my way out of. As Resmaa Menakem writes in My Grandmother’s Hands, “white-body supremacy doesn’t live in our thinking brains. It lives and breathes in our bodies” (5). Habits of colonial accumulation are deeply embedded in my cultural and literal fibres: in my muscle memory, in the textiles that surround me. These become not also visible but also unavoidably tangible via an exercise that I am calling devirtuous mending: mending that attempts to resist the accumulation of virtue, that works to de-virtue, to remove or sidestep this sort of clawing after power, this clinging to (white) position. #DevirtuousMends inches toward mending practice that speaks to the unfinished and unfinishable nature of mending, of repair, and that interrupts the link between perfect darns and perfect selves. In attempting to mend devirtuously, I aim to decouple virtue from the practice of needlework—and instead to participate in the reciprocity of mending—the reality that the mending works upon the mender, and that the mender owes the mending for this gift, without the end result being the wearing of a badge of honour. I want to mend beyond individual accomplishment and toward collectivity. Rather than the neatness of an impenetrable darn, I strive for entanglement—what Donna Haraway calls “staying with the trouble.”

Here is one final visible mend for you: a writerly patch that I might have removed from this essay at one time. Begun in the wake of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s work, this reflection goes out now after having sat for a long while, not unlike the mending pile, emerging into a very different moment, on the other side of the COVID-19 pandemic, when public discourse is less reconciliatory and more overtly fascist, in which we are perhaps even more organized around crisis, around urgent action… I note that in the elapsed time, I have not in fact launched a public practice of #DevirtuousMending, unless that is what one can call resigning from academia mid-career. I mend, though not enough, and quietly, privately–for the sake of practicality, not show. My child’s sock; a friend’s hat; a moth-sheltering sweater.

Although now somewhat distant from the intellectual and social contexts wherein ongoing artistic research might seem possible, I sometimes imagine walking in mended socks whose loose ends remain unwoven. The unfinished threads reach, stretch, tangle, pull out, puckering the fabric, maybe catching on a jagged bit of flooring or adhering to the grass. While inconvenient (and not a little bit strange), the looseness of these threads renders the garment ‘open’ and unfinished, accessible to the world in a different way, rather than creating a neat barrier between the wearer and the surface underfoot. Instead, I picture the threads sinking rootlike into the soil, thus ‘fixing’ the wearer, perhaps decaying, even feeding the grass whose nutrients grew the wool on the backs of sheep—or lingering, in the case of yarns spun from synthesized petroleum products, a long time, too long, remaining instead a permanent homage to entanglement. Here the mend fails to preserve, to prolong, to elevate, its hole of origin instead becoming a rupture, a spilling, a break, a site of undoing, a point of possible encounter—

[1] As the Swiss jurist Emmerich de Vattel wrote in 1758, “The whole earth is destined to feed its inhabitants; but this it would be incapable of doing if it were uncultivated…. There are others, who, to avoid labour, choose to live only by hunting, and their flocks…. Those who still pursue this idle mode of life, usurp more extensive territories than, with a reasonable share of labour, they would have occasion for, and have, therefore, no reason to complain, if other nations, more industrious and too closely confined, come to take possession of a part of those lands” (35-36). Roger Epp describes Vattel’s influence upon John Locke, who likewise promoted the idea that uncultivated or ‘idle’ lands were available for legitimate seizure (Epp 127-129).

[2] “Just in time for Canada Day, economy is clearly on the mend,” read a June 28, 2019 headline in The Star (Argitis and Bloomburg).

[3] The New International Version reads “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven has come near” (“Matthew 3:2 NIV”).

[4] “Once embroidery had become an accepted tool for inculcating and manifesting femininity in the privileged classes, with missionary zeal it was taken to the working class. Teaching embroidery to the poor became an aspect of Victorian philanthropy” (Parker 173).

[5] On the Living Healing Quilt Project, see Kristy Robertson’s “Threads of Hope”; for the Bentwood box blankets, see “Bentwood Collection”; for Ribbons of Reconciliation, see “Personal Ribbon Campaign”; for Orange Shirt Day, see orangeshirtday.org; on the blanket mending project, see Jesse Mintz, “Mending Blankets, Changing Lives.”

[6] I am grateful to Rosa Wah-Shee for this conversation—and for her permission to include her experience here.

[7] Here I am indebted to the work of scholars like Leanne Betasamosake Simpson and Audra Simpson, who (among others) have made plain the important labour of refusing state efforts at ‘reconciliation.’

[8] See Mrs. Sew-and-Sew’s instructions (as issued by the wartime British Board of Trade): “Do not wait for holes to develop. It is better to darn as soon as garments begin to wear thin” (Make Do and Mend 17).

[9] Then-Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s 2008 apology to Indian Residential School students in the House of Commons began with the lines,“I stand before you today to offer an apology to former students of Indian residential schools. The treatment of children in these schools is a sad chapter in our history” (qtd. in Parrott).

[10] For the story of the late Colten Boushie and the exoneration of his killer, see Tasha Hubbard’s 2019 film nîpawistamâsowin: We Will Stand Up.

[11] As I write this in early 2020, Wet’suwet’en land defenders working to stop Coastal GasLink from building a natural gas pipeline through their territories are being raided, monitored, and harassed by RCMP authorized to use lethal force (Dhillon and Parish). Meanwhile, young Indigenous climate activists are likewise trying to halt the approval of a new open-pit tarsands mine (Teck Resources Ltd.’s Frontier project) in northeastern Alberta (Wyton).

[12] My “strategies of disengagement” echoes Sam McKegney’s critique of non-Indigenous scholars’ tactics of shedding responsibility for doing the hard work of reading Indigenous literatures in his 2007 book Magic Weapons (pp. 39-41).

[13] Donald defines colonialism as “the ongoing process of denying relationship,” in multiple senses.

Works Cited

“amend, v.” OED Online, Oxford University Press, September 2019, www.oed.com/view/Entry/6300. Accessed 25 November 2019.

Argitis, Theophilos and Erik Hertzberg Bloomberg. “Just in time for Canada Day, economy is clearly on the mend.” The Star, 28 June 2019, https://www.thestar.com/business/2019/06/28/just-in-time-for-canada-day-economy-is-clearly-on-the-mend.html. Accessed 24 Jan. 2020.

“Bentwood Collection.” National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, University of Manitoba, https://nctr.ca/assets/reports/bentwood2.pdf. Accessed 29 Jan. 2020.

Dhillon, Jaskiran and Will Parish. “Exclusive: Canada police prepared to shoot Indigenous activists, documents show.” The Guardian, 20 Dec. 2019, https://gu.com/p/dvb32/sbl. Accessed 30 Jan. 2020.

Donald, Dwayne. “Homo Economicus and Forgetful Curriculum.” Winter 2020 Sustainability Lectures, Sustainability Council, 23 Jan. 2020, University of Alberta. Lecture.

Epp, Roger. We Are All Treaty People: Prairie Essays. U of Alberta P, 2008.

Fletcher, Kate. Craft of Use: Post-Growth Fashion. Routledge, 2016.

Frost, Robert. “Mending Wall.” Representative Poetry Online, University of Toronto Libraries, 1998, https://rpo.library.utoronto.ca/poems/mending-wall. Accessed 24 Jan. 2020.

Futuremenders: Ushering in the Age of Mending. https://futuremenders.wordpress.com/about/

Accessed 28 Jan. 2020.

Hákonardóttir, Halla. The Role of the Hole: To explore the notion of a garment and its relation to a body through life size action collages and material interlocking. 2015. University of Borås, MA Thesis, http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:840927/FULLTEXT01.pdf. Accessed 23 Jan. 2020.

Haraway, Donna. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke, 2016.

Jordan-Fenton, Christy and Margaret Pokiak-Fenton. Fatty Legs. Annick, 2010.

Justice, Daniel Heath. Why Indigenous Literatures Matter. Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2018.

Lomawaima, K. Tsianina. “Domesticity in the Federal Indian Schools: The Power of Authority over Mind and Body.” American Ethnologist, vol. 20, no. 2, 1993, pp. 227-240. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/645643. Accessed 10 Dec. 2019.

Mackey, Eva. “The Apologizers’ Apology.” Wakeham and Henderson, pp. 47-62.

Make Do and Mend: Keeping Family and Home Afloat on War Rations. Michael O’Mara Books, 2007.

“Matthew 3:2 NIV.” Biblica: The International Bible Society, https://www.biblica.com/bible/?osis=niv:matt.3.2. Accessed 24 Jan. 2020.

McKegney, Sam. Magic Weapons: Aboriginal Writers Remaking Community After Residential Schools. Foreword by Basil Johnston. U of Manitoba P, 2007.

Middleton, Jonnet. “Long live the thing! Temporal ubiquity in a smart vintage wardrobe.” Ubiquity: The Journal of Pervasive Media, vol. 1, no. 1, 2017, pp. 7–22, https://doi.org/10.1386/ubiq.1.1.7_1. Accessed 28 Jan 2020.

—. “Mending.” Routledge Handbook of Sustainability and Fashion. Edited by Kate Fletcher and Mathilda Tham, Routledge, 2014, https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203519943.ch26. Accessed 04 Jul. 2018.

Milloy, John S. A National Crime: The Canadian Government and the Residential School System, 1879 to 1986. U of Manitoba P, 1999.

Mintz, Jesse. “Mending Blankets, Changing Lives.” WE Charity, 2020, https://www.we.org/en-CA/we-stories/local-impact/canadian-students-come-together-to-learn-about-reconciliation-and-social-justice. Accessed 24 Jan. 2020.

nîpawistamâsowin: We Will Stand Up. Directed by Tasha Hubbard. National Film Board, 2019.

Orange Shirt Day. orangeshirtday.org. Accessed 28 Jan. 2020.

Parker, Rozsika. The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine. Tauris, 2010.

Parrott, Zach. “Government Apology to Former Students of Indian Residential Schools.” The Canadian Encyclopedia, Historica Canada, 14 July 2014, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/government-apology-to-former-students-of-indian-residential-schools. Accessed 30 Jan. 2020.

Paxton, Katrina. “Learning Gender: Female Students at the Sherman Institute, 1907-1945.” Boarding School Blues: Revisiting American Indian Educational Experiences, edited by Clifford E. Trafzer, Jean A. Keller, and Lorene Sisquoc, e-book, U of Nebraska P, 2006, pp. 174-86.

Pedri-Spade, Celeste. “The Day My Photographs Danced: Materializing Photographs of My Anishinabe Ancestors.” Visual Ethnography, vol. 6, no. 1, 2017, pp. 133-172.

“Personal Ribbon Campaign.” Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, http://www.trc.ca/reconciliation/trc-initiatives/personal-ribbon-campaign.html. Accessed 24 Jan 2020.

Richardson, Charles. A New Dictionary of the English Language. Pickering; Jackson, 1839. Internet Archive, 15 July 2008, https://archive.org/details/anewdictionarye00richgoog/page/n8/mode/2up. Accessed 24 Jan. 2020.

Robertson, David. When We Were Alone. Illustrated by Julie Flett, Highwater P, 2016.

Robertson, Kristy. “Threads of Hope: The Living Healing Quilt Project.” English Studies in Canada (Aboriginal Redress and Repatriation), vol, 35, no. 1, 2010, pp. 85-108.

Shotwell, Alexis. Against Purity: Living Ethically in Compromised Times. U of Minnesota P, 2016.

Simpson, Audra. “Reconciliation and Its Discontents: Settler Governance in an Age of Sorrow.” University of Saskatchewan, 15 Mar. 2016. YouTube, uploaded by University of Saskatchewan, 22 Mar. 2016.

Simpson, Leanne Betasamosake. “Restoring Nationhood: Addressing Land Dispossession in the Canadian Reconciliation Discourse.” Simon Fraser University, 13 Nov. 2013. YouTube, uploaded by Simon Fraser University, 13 Jan. 2014.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Canada’s Residential Schools: The History, Part 1: Origins to 1939. The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, vol. 1, part 1, McGill-Queen’s UP, 2016.

—. What We Have Learned: Principles of Truth & Reconciliation. Truth & Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication, 2015.

Tuck, Eve and K. Wayne Yang. “Decolonization Is Not A Metaphor.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, vol. 1, no. 1, 2012, pp. 1-40, https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/des/article/view/18630. Accessed 23 Jan. 2020.

Van Deijnen, Tom [Tom of Holland]. TOMOFHOLLAND: The Visible Mending Programme: making and re-making. https://tomofholland.com/. Accessed 28 Jan. 2020.

Vattel, Emer de. The law of nations, or, principles of the law of nature, applied to the conduct and affairs of nations and sovereigns. G.G. and J. Robinson, 1897. Eighteenth Century Collections Online, Gage, University of Alberta Libraries. Accessed 28 Jan. 2020.

Vowel, Chelsea. “Back To The Land: 2Land2Furious.” âpihtawikosisân: law, language, culture, 29 July 2019, https://apihtawikosisan.com/2019/07/back-to-the-land-2land2furious/. Accessed 23 Jan. 2020.

Wakeham, Pauline and Jennifer Henderson, editors. Reconciling Canada: Critical Perspectives on the Culture of Redress. U of Toronto P, 2013.

—. “Colonial Reckoning, National Reconciliation? Aboriginal People and the Culture of Redress in Canada.” ESC: English Studies in Canada, vol. 35, no. 1, 2009, pp. 1-26. Project Muse, 26 June 2010, https://muse-jhu-edu.login.ezproxy.library.ualberta.ca/article/384482. Accessed 30 Jan. 2020.

Wolfe, Patrick. “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native,” Journal of Genocide Research, vol. 8, no. 4, 2006, pp. 387–409.

Wyton, Moira. “Indigenous-led climate protesters occupy Canada Place against proposed mine. Edmonton Journal, 22 Jan. 2020, https://edmontonjournal.com/news/politics/indigenous-led-climate-protesters-occupy-canada-place-against-proposed-mine. Accessed 30 Jan. 2020.

A white-bodied ex-academic turned fibre millworker, Keavy Martin lives with her family in Edmonton, Alberta, courtesy of the ongoing legal agreement known as Treaty No. 6, and within Region 4 of the Métis Nation of Alberta. She attempts relationship through textile and fibreshed work, particularly mending, which she practices when not parenting, playing music, or wrestling a pin-drafter at Qiviut Inc. Fibre Mill.

A white-bodied ex-academic turned fibre millworker, Keavy Martin lives with her family in Edmonton, Alberta, courtesy of the ongoing legal agreement known as Treaty No. 6, and within Region 4 of the Métis Nation of Alberta. She attempts relationship through textile and fibreshed work, particularly mending, which she practices when not parenting, playing music, or wrestling a pin-drafter at Qiviut Inc. Fibre Mill.