Appendix II: Métis Impact Statements on Four Generations of Trauma as a Result of Indian Residential and Day Schools

by Jason Baerg and Doris Lanigan

Indigenous communities have always known.

Children offered first-hand accounts.

Survivors led us right to the graves.

The work of Truth before Reconciliation is crucial as it necessitates accountability and responsibility. These things need to be in place to build and maintain trust between Indigenous Nations and Canada. Better futures are only possible for all parties when foundational agreements are honoured, and the best terms for the relationship continue to be cultivated. Unfortunately, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) has failed to address the impacts of the residential and day school system on Métis people in a meaningful way.

This paper is an account of some of the experiences and impacts of the residential school system on my Métis family. This account illustrates how justice is absent for Métis survivors, which causes continued violence against Métis people across these lands. A brief history of Métis participation in the movement for Truth and Reconciliation, and some possibilities for action follows.

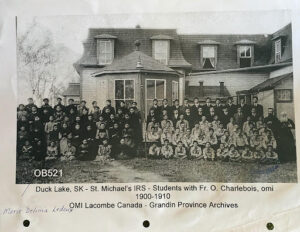

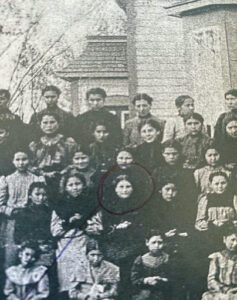

Fig.1. My Great Grandmother Marie Delima Ledoux attended St Michael’s IRS (Duck Lake, SK-St. Michaels’s IRS OB3628, 1900-1910, Provincial Archives of Alberta, Edmonton, AB)

I come from Treaty 6 Territory. My Métis Grandmother, Lorette Gagnon-Lanigan, was born in Moon Hills, Saskatchewan, just outside Muskeg Lake Cree Nation, where we still have blood relations who are band members. Grandma Lorette married my Grandpa Jack Lanigan, and they had nine children in Big River, where my mom was born and raised. My grandmother passed at 42 from causes that my mother believes are due to residual residential school trauma. I was raised by my mother Doris Lanigan and Grandfather Jack Lanigan and lived in Prince Albert from age seven to fifteen. Our local extended Métis family was close-knit as my mother’s sisters, Theresa and Helen, and their children lived within blocks of our home. My Uncle Brian also lived in the area for most of those years. My Aunt Shirley, who lived in Saskatoon, often participated in family engagements with her children.

These strong Métis people raised their children in this familial support network. I had my Métis Nation of Saskatchewan citizen card, which framed my complex identity as a young person. Growing up in the 70s and 80s in an urban environment provided context to my Indigeneity, which was also obscured by a colonial rupture of culture and was compounded by racism. It was shameful to be Indigenous in the region at the time. This results from the impacts of residential schools and other extensions of genocide, including the ever-present correctional systems that continue to institutionalize our people. Prince Albert, population 36,000 (2021), is a prison town with four correctional facilities.

Fig.2 Close up of my Great-Grandmother Marie Delima Ledoux in front of St. Michael’s Indian Residential School in Duck Lake. (Duck Lake, SK-St. Michaels’s IRS, 1900-1910, Provincial Archives of Alberta, Edmonton, AB)

On November 23, 2018, I enjoyed a dynamic lecture by Plains Cree curator, Dr. Gerald McMaster, as part of Dr. Suzanne Morrissette’s lecture series at OCAD University entitled “Expansive Approaches to Indigenous Art Histories”. The large classroom held approximately 75 people in attendance. Gerald spoke about Indian Residential Schools and noted that they did not impact Métis people at one point in the talk. I was sitting in the second row and did not hesitate to let him know that this was not true and that my Great Grandmother, Marie Delima Ledoux, went to St. Michael’s Indian Residential School in Duck Lake Saskatchewan. He immediately acknowledged this point to the room and humbly accepted the correction.

The erasure of Métis history and the impact of residential schooling on Métis people is not surprising. Lee Marmon’s “Final Report on Métis Education and Boarding School Literature and Sources Review,” prepared for the Métis National Council (February 2010), states:

The study and understanding of the Métis school experience has been impeded by three fundamental factors: (1) the unwillingness of the federal and provincial governments thus far to formally recognize that the provinces and religious denominations have a duty to accept responsibility for the Métis educational experience equivalent to federal recognition and compensation; (2) the research focus on federal residential schools is largely dominated by the experience of First Nations students as a consequence of this perspective; (3) the scarcity of Métis-specific educational research at any level (Marmon 2010, 01).

Yet, the Métis were there, as I can testify in my own family’s experiences. The Roman Catholic Church (Oblates of Mary Immaculate, Sisters, Faithful Companions of Jesus, Sisters of the Presentation of Mary, and Oblate Indian-Eskimo Council) operated St. Michael’s Indian Residential School. My mother attended the Convent in Victoire, Saskatchewan, run by the Daughters of Providence. The Convent in Victoire is listed in Appendix II in the IRS Federal Settlement Agreement under “Currently Disapproved/Pending Approval Schools.” Sadly, every school I attended in Prince Albert (1977–1985) is also included in Appendix II. Some of my memories of these schools are clear testimonies of abuse and trauma. As of 2025, I have applied for reparation through the Federal Indian Day School Class Action and still await the government’s acknowledgement that there were Métis People in Prince Albert significantly impacted.

What is Appendix II in the IRS Federal Settlement Agreement?

The institutions listed [in Appendix II] have been requested to be added to the list of Indian residential schools recognized by the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement. These requested institutions have been researched by Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada and assessed against the test in Article 12 of the Settlement Agreement for determining whether the institutions should be considered an Indian residential school (Article 12 New Decisions 2012).

Métis people have been greatly affected by the residential school system. We have also stood beside our kin to advocate for Truth and Reconciliation since the beginning of the movement. Tricia E. Logan, a Métis scholar and the head of Research and Engagement at the University of British Columbia’s Residential School History and Dialogue Centre, has written about Métis involvement with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. She states the following:

During the 1980s and 1990s, an increasing number of Survivors came forward with stories about their experiences at residential school. Eventually, they started to bring lawsuits against the federal government and churches. Métis Survivors were part of those early movements. The Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement (IRSSA) was limited to federally funded schools, and many Métis were left out of the compensation process. As a result, some Métis also felt left out of the TRC’s gatherings and processes, which took place from 2008 to 2015.

Métis Survivors have shared that their feelings of being outsiders in both the TRC and compensation processes are similar to how they felt like outsiders in the residential schools. Despite often feeling lost or less visible in the processes, many Métis Survivors still came forward to provide statements to the TRC and participate in national and regional gatherings. They wanted to ensure that Métis voices were heard and that their experiences at residential school were considered in the TRC’s proceedings.

In 2009, Survivors of federal Indian day schools, many of whom were Métis, launched a class-action suit seeking compensation for their experiences at the schools. While day-school Survivors were able to return home each day, many of the problems with and impacts of assimilation, language removal and abuse were as present as they were in residential school. In 2019, the government announced that it would settle. In January 2020, over a decade after the suit was launched, day-school Survivors were finally able to start applying for compensation (Logan 2020).

Here, I will write about what can be substantiated by archival records. I will also write about a contested perspective within my family, which results from the colonial reality that there is a plethora of buried or missing data on the residential schools that also impacts Métis history telling.

In offering aspects of my familial account, I hope to pose important questions and to search for healthy roads forward on how to deal with these histories caused by colonial trauma. This story is told from my perspective, and I put tobacco out to honour Tapwewin (Truth) so that these stories are shared in a way that is intended to heal and lead to vibrant family and community interaction. I will tell the story of residential school impacts from my perspectives and the perspectives of my mother’s generation. In doing so, this paper honours the process of sharing our stories and supports further collective efforts to record histories, as the documented impacts of residential schools on Métis people are limited. I offer this account not as a scholar but as an Indigenous community member with the intention to open healthy dialogue about the repercussions within my family, and to create space for other Métis people to step forward in strength. I hope to offer a space of healing for those in the Métis community and beyond.

Fig.3 (Indian Boys of the Duck Lake Boarding School working on the new addition, 1900s, United Church of Canada, Toronto, ON.) – Digital Collections 93.049 P2021 N

Histories are complicated and perceived differently from various perspectives. My mother has a different understanding of the past than one of her younger sisters, who, in her own right, is a respected scholar and historian in our family. My uncle, the eldest in my mother’s family, validates my mother’s testimony. I love them all and do not want to create any harm between family members. I report on substantiated facts, yet both stories are convincing, and I am sure they both hold truths. Out of deep respect for the subject and dealing with issues of identity that assimilationist policies have compounded, meaningful conversations have happened in my family as part of this research. It was vital for me to return to Saskatchewan to engage in this work in the physical presence of family members.

The questioning of a painful past leads to critical discussions of Métis futurities. What does it look like or mean to be Métis today? We must acknowledge that the Métis Nation was born organically from necessity but is a colonial construct as our Indigenous ancestors formally organized due to rising Canadian nationalism.

Louis Riel wrote: “The Métis have as paternal ancestors the former employees of the Hudson’s Bay and North-West Companies, and as maternal ancestors’ Indian women belonging to various tribes. The French word Métis is derived from the Latin participle mixtus, which means “mixed”; it expresses the idea it represents. Quite appropriate also, was the corresponding English term “Half-Breed” in the first generation of blood mixing, but now that European blood and Indian blood are mingled to varying degrees, it is no longer generally applicable” (Riel as quoted in Trémaudan 1982, 200).

We sit in the Indigenous circle; thus, what does it mean to honour our Indigenous practices, histories, and cultures? What lessons or teachings should we be privy to? What language(s) should we have access to? Indigenous cosmologies are embedded in our songs, stories, food, ceremonies and teachings. Connection to place and medicines are situated in the tongue of the land. How should we practice our spirituality? We are not tethered to any constructed colonial system, yet many complex considerations and ideologies influence us. Who has the right to define who we are and what we want to do? Métis people deserve the right to receive their teachings, medicines and the knowledge intended for us as the inheritance from our ancestors. We have the right to self-governance and sovereignty. This has been ruptured by colonialism and the residential school system. Despite all the complexity, we need to move towards healthy roads forward.

The formal need to organize as a Métis Nation was also a result of colonial violence, which is illustrated by our histories of armed resistance and revolt. We are now charged with building a solid Nation with integrity and respect for our Indigenous relations. Conversations with our First Nations brothers and sisters could assist in the healthy development of our Métis culture as our actions and decisions affect them and everything they have worked so hard to maintain. We are extensions of each other; the land, languages, and ceremonies are ours to protect and share with kin. Cultures are organic and evolve. Because our voices as Indigenous peoples have been silenced, we need to take back our power with action and stand in the circle with purpose in solidarity and complete respect for each other and ourselves.

Residential schools carried a behavioural mandate issued by the first Prime Minister of Canada, Sir John A. Macdonald, “to take the Indian out of the child.” As a result, great atrocities have occurred. The violence issued because of the intentions of these “corrective” measures spilt beyond the residential schools into other institutions that were similarly supporting the vision of a new Canada. Many of the Appendix II schools were established and run by the same clergy members who applied similar pedagogical approaches and disciplinary measures in the residential schools.

Fig. 4 Quartz for healing my aunt’s leg rests on top of an image of the dorm beds at St. Michael’s Residential School in Duck Lake, Saskatchewan (Duck Lake, SK, St. Michael’s, IKS, Dormitory OB3628 (cropped), 1926, Provincial Archives of Alberta, Edmonton, AB.)

It is never easy to talk about painful family histories. I had a conversation with my mother. We start with tea poured for our ancestors. A cup is poured for my mother and me. Two extra cups are poured for my Indigenous grandmother and great-grandmother, both of whom have passed on. This is done to feast them.

This work is done sensitively, and I am grateful to my family who have helped recover and inform these histories. After my mother offered her perspective, I travelled to Saskatchewan from Toronto to find evidence of the residential school experiences in my family through photographs and personal testimonies. I have recently also discussed this history with the eldest sibling in my mother’s generation, and he confirmed the accuracy of these accounts.

The following is a transcript of my mother’s intergenerational experiences of the residential school impacts. My Mother, Grandmother and Great Grandmother are survivors. This conversation happened in July 2020.

Hello, my name is Doris Lanigan, and I am a Métis Elder and elected Senator, serving my third term with the Métis Nation of Ontario. I am here to talk about some of the experiences of my ancestors. My grandmother, Marie Rose de Lima Ledoux-Gagnon, and my mother, Lorette Gagnon-Lanigan who were both residential school survivors.

I lived with my grandmother (Marie Rose de Lima Ledoux-Gagnon) and frequently inquired about her life. She did not want to talk about her childhood or school years because of the associated trauma. She did tell me about experiences that she was ashamed of and embarrassed by; she was unsure of her actual birthday. The children of the residential school didn’t have birthdays, which offered acknowledgement, or parties. My great-grandmother’s mother (Marie Moreau) died when grandma (Marie Rose de Lima Ledoux-Gagnon) was six, and therefore she did not know exactly how old she was. My grandmother (Marie Rose de Lima Ledoux-Gagnon) attended St. Michael’s Residential School from [age] six until she was fourteen (1902-1910). She thought she was 16 when she ran away from residential school to marry her first husband. (She fled because the IRS wanted to marry her off to a very old man.) Later in life, when she thought she was 65 and applied for her old age pension, she was denied because, at the time, she was federally recognized as 63. It was humiliating that the past could come back so many years later and make her feel bad about herself.

The residential school children of those times were not given the elementary things to grow healthy, strong and confident; love, affection, and acknowledgement were withheld. The abuses against them are well chronicled, as were the horrendous conditions these children had suffered. The children also had many chores to manage while concurrently going to school.

My mother, Lorette, also went to [residential] school and was sent home at [age] ten with an injury. Someone kicked her, and she got an abscess on her side. There are several conflicting stories around this injury as to how it happened and who inflicted this upon her. She nearly died and was hospitalized for months. This affected her health for the rest of her life. She died at the age of forty-two with a tumour on that side of her body.

When my mother Lorette was hurt at [residential] school, my grandmother (Marie Rose de Lima Gagnon, nee Ledoux) and grandfather (Edmond Gagnon) packed up. They moved from Saskatchewan to North of Kenora, Ontario, near Lake of the Woods in a cabin back in the bush. When I asked my grandmother why my aunties and uncles did not go to school, she sometimes said they had no shoes yet said it was better for her children not to have shoes or any education than going to a residential school. Despite challenges, my mother and my grandmother were smart, strong, kind, and loving. They were good people, and I am so proud of them. They were resilient, resourceful, and cheerful. They were always willing to help others in every way they could. I loved them and grew up wanting to be as brave and admirable as they were.

When I was in grade seven, I attended Victoire, a convent run by the Daughters of Providence (who celebrated 200 years as nuns in Saskatchewan in 2018), the same Order of nuns that ran St. Michael’s Indian Residential School. They did not hurt me or make me feel bad about myself, but they certainly took advantage of my willingness to work hard. I was a boarder student at the convent under the conditions that I would work for my room and board instead of tuition. I was raised with love and affection at home and was taught to take responsibility for the younger children and help whenever I could, so I did not question earning my keep.

During my stay at Victoire, a few incidents happened, and I intervened at the time of concern. One situation was when a ten-year-old child was put into the cubbyhole under the stairs as punishment for bad behaviour. The cubbyhole had a door with rusty spike nails hammered through it from the outside to the inside of this small, enclosed space. If the person inside the cubbyhole tried to push the door open, the spikes would pierce their hands. I came from a large family of nine and had responsibilities for the younger children; therefore, I had to advocate in this situation. I begged them not to put the child in the cubbyhole. They did not listen, so I went to the priest and begged him to come and stop them. He finally saw reason, and he went to the convent and prevented them from putting the child in the cubbyhole. I warned both the nuns and the priest that I would tell this child’s father, my father, and the RCMP if they did not stop. I went on to further express that I would alarm all the people in the hamlet as to what they were doing. The next day, they had a repairman board up the cubbyhole and put new drywall over the opening to look like it had never been there. Both the priest and the nuns knew of my family’s prior history under the care of their Order. I was not reprimanded for intervening.

The second incident occurred when the nuns force-fed a six-year-old female because she could not eat dinner. She had been sick for several days before this force-feeding happened. I intervened again and begged them to stop force-feeding the child, yet they did not stop until the child threw up all over the table. She was already sick, and now her mouth was also bleeding. I asked Mother Superior to call her parents, but she refused, stating the girl could wait until Friday. It was Wednesday. I pleaded that she was already incredibly sick and inquired what would happen if she died before Friday. The convent called her parents, and gratefully her parents were visiting nearby and were at the door shortly after. Mother Superior asked me to take her upstairs and clean her up right away. I did the best I could and then carried her down to her parents. When her mother saw how sick she was and her bleeding mouth, she started crying and demanded to know what had happened. I told her everything. They did not bring the child back to the convent.

The third incident occurred that year when I was in grade seven after a nun became very ill. Instead of hiring a new teacher, they had me teach grades one through four from January to June, including twenty children. I also taught catechism to grades seven and eight. My condition of staying at the convent was to work for my room and board, as my family had no money to pay for my stay. This situation left me working at the convent and teaching on top of managing my schoolwork at night when everything else was complete. My day began at 5:00 a.m. getting myself ready and then assisting the smaller children in starting their day.

As a result of the force-feeding incident, the parents went to the school board, and the superintendent of schools visited the convent. He came to my classroom to ask for the teacher. I told him I was the teacher, and he asked why, which launched a deeper inquiry of activities at the school. He invited himself for dinner and insisted I not serve the nuns but get a plate, sit down, and have dinner with them all. We had a meeting discussing child labour. The superintendent inquired why they had not reported that the teacher was off sick while taking the nun’s salary from the school board and having a young student implement the classes instead. They also discussed what was appropriate punishment and what was not. He was a great advocate for me and all students and promised to make regular visits to check up on the school as there were complaints. He also made it very clear that I had worked hard enough and, as a result, noted that I could continue to stay at the convent for free if I wanted, without having to work for the nuns any further.

A fourth incident occurred early that spring on a Friday. There had been a meeting at the convent that included the nuns, the local parish priest, and the parish priest from my hometown, Big River. The priest from Big River offered to drive me home as he was going there anyway. [It was] about 10 p.m. when we left, and about fifteen kilometres from my home, he suddenly drove off the road into the bush and got firmly stuck. He turns to me and says, “Oh well, I guess we have to stay overnight here.” I declared, “Absolutely not!” I jumped out of the vehicle, looked at the position of the car, and proceeded to try to get us out. He had an axe in the car’s back seat, and I took it out to cut spruce boughs and put them under the wheels for traction. When I asked him to drive out, he made very lame efforts to do so. He never got out of the car to assist. Finally, I told him if he didn’t help, my father would not be pleased, so he better help. He still didn’t try to get the car out of the ditch. In exasperation, I told him I would yank him out of the car and drive the car out myself. I finally arrived home at 2 a.m. My passive, gentle mother, who never raised her voice to anyone, was so upset she screamed at him: “I know what you were going to do to my girl. I know you. You wanted to humiliate her. I know you.” He kept saying “sorry, sorry” and backed out of the door and left. I slept beside my mother for the rest of the night as she cried herself to sleep. Our family suffered multiple generations of abuse.

I hope in the future that these things will not happen to anyone again; however, we still hear of bad things happening to children, and we must be ever vigilant to watch out for young people to stop the abuse. We must acknowledge that these things happen to children, and when they tell us, we must believe them and report [the] incidents no matter the consequences—Every Child Matters.

Fig. 5 (Prince Albert (SK) OB3628, Dates of Operation July 1, 1894 – June 30, 1997, Provincial Archives of Alberta, Edmond, AB. https://collections.irshdc.ubc.ca/index.php/Detail/entities/1174 )

My Personal Journey

I have my own experiences. There is still deep fear in our family and I respect that people need to feel safe. I remember going to a retreat for emerging Indigenous arts administrators in Edmonton, Alberta, at the Poundmaker’s Lodge Treatment Centre. Louise Profeit-LeBlanc led the conversation as the Aboriginal Secretariat at the Canada Council for the Arts. She is a strong, respected matriarch in the community. She facilitated the gathering with much thought and genuine care. She shared ceremony and culture generously. We made a new bundle where we all added to the sacred holdings intended to better all our communities. In a circle in ceremony, she asked us all to utter the names of our Indigenous ancestors aloud.

Fear.

I called out my grandmother’s name, the woman who left before I was born, and left my mother to care for four young children when she was 19. I called out her name.

Fear.

After my grandmother passed, my mother also took care of her father, who also helped raise me. I immediately heard his voice. In my head, in my heart, in my spirit, I heard him say, “You leave your grandmother out of this!” I felt like he was trying to protect her. But why all this fear? Even from the other side? Residential schools were designed to steal power, to assimilate, to oppress.

I take power back; I will not be afraid. Tapwewin.

Some people say, “you don’t look Indigenous,” and then speak to my white ancestors who stand behind me. Some people say, “I see you, acknowledge you,” and then talk to my Indigenous ancestors who stand behind me.

I attended multiple Appendix II schools in Prince Albert. First Nations children were housed at the barracks of the Prince Albert Indian Residential School. It no longer held classes, so the students were educated in the same schools I attended.

Prince Albert Indian Residential School was a Canadian residential school operated by the Anglican Church for First Nations children in Prince Albert. The Prince Albert school was established in 1947 to take in students from the Anglican school at Lac La Ronge. The school was established in what was originally meant to be a temporary location in a former army base on the edge of Prince Albert. Instead, the Prince Albert school grew to be the second-largest residential school in Canada. After 1961 the school was used as a residence to house students attending local day schools. In 1969, the federal government took over the administration of the school. First Nations played a growing role in the administration of the residence, which closed in 1997. (NCTR, “Archives”, 2022.)

These Indigenous children came to school embodying intergenerational trauma as abuse was rampant at the Prince Albert Indian Residential School. As a result, violence was common in the classroom and on the playground. There were numerous violent bullies at Saint Paul’s, which I attended from grades one to four. I landed in the hospital twice with significant injuries. Intergenerational traumas echoed through most of my schoolyard peers. The extreme “accidents” at recess would leave me bleeding in the hallways, while the unresponsive teachers played cards right in front of me, even though we were across the street from a hospital. My left eyebrow was split open after my feet were kicked out from under me at the top of an icy hill. Another time the same schoolmate jumped off the monkey bars onto the teeter-totter, chipping my front teeth, breaking my nose, and splitting my lips. Both times, I waited for my mother to come from work to take me to that hospital across the street from the school.

In Grade 5 at Saint Michael’s, the teacher knocked me out of my desk with a stack of books sending me flying into the aisle. On another occasion, that same teacher dragged me up three flights of stairs by the back of my hair and leather-strapped me for laughing in the library. After the strapping, he excused me to pull myself together in the bathroom and mentioned that I could come back to class after I had composed myself. I stayed in that basement bathroom for the next two school days. I would go into school, hang up my coat in the classroom, go to the bathroom, and hide in a stall until he finally came down, apologized, and begged me to come back to class. He knew he overstepped his authority and abused me.

In the West Flat neighbourhood in Prince Albert where I grew up, just blocks away from the federal penitentiary, there were three sexual predators I had to run from constantly. Talk echoed through my peer network; it was clear that many children were having sex with adults and that this activity was very easy to become engaged in. I avoided this and found myself sticking very close to my family. Disparity resonated in my mental, physical, and spiritual being. Hope, the desire to escape, and the need for validation are not things children should ever crave, but ultimately, they became my survival mechanisms. When I self-reflect, it is no surprise I became an artist as this was a way to creatively rectify everything I had experienced as well as build visions of healthy futures for myself and the world I know and love. Escapisms to brighter futurities became the aspirational impetus.

In Grade 8, while attending Queen Mary’s School, the bullying became so intense it triggered my mother to send me to Ontario to be raised by my father. The violence was extreme and sexual shaming was constant. These behaviours occurred because intergenerational trauma echoes through the community. Mom knew she had to spare me further trauma to save my life.

I am certain that what my great-grandmother faced while attending St. Michael’s Residential School was torture, understanding that when she attended, 50% of the students were dying while in “care.” In Shattering the Silence: The Hidden History of Residential Schools in Saskatchewan, Sharon Niessen reports on this history:

In 1910, Indian agent J. MacArthur reported “that the death rate at the Duck Lake school (St. Michael’s IRS) was returning to its ‘high mark.’ Two students had died and two others were dying.” He estimated that 50% of the children sent to the school had died. MacArthur understood that children were getting sick at the school, rather than at home as some believed, pointing out that children “spent only one month a year at home. During that month, they spent their time on the open prairie and slept in tents.’ The rest of the year, they were in the school. ‘No one responsible can get beyond the sad fact that those children catch the disease while at school” (2017, 92).

The ramifications of the trauma recur through generations as various abuses occurred. Reflecting on my family’s residential school histories helps me rationalize dysfunctions in my peers and my community, while concurrently filling me with love, inspiration, and motivation. When I look at my Métis family today, I am so proud of them all as they move forward to make purposeful and meaningful contributions in the wake of adversity. There is still a call to action, and that is for healing and cultural reclamation. Truth before reconciliation.

The reliving of these painful stories is done in support of other Métis people who survive in the wake of the Indian Residential Schools. How can we act? We can work on ourselves, find support in our communities, and move towards building cultural safety, inclusion, and better futures. Apply for reparations if you have the strength and capacity. We have the right to speak our truths and engage in reconciliation, which might be necessary for healing and growth.

**

In May 2021, the rest of the public was informed about the unmarked graves of residential school children in a media release from Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc (Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc Kukpi7 (Chief) Rosanne Casimir 2021). This news triggered heightened levels of trauma in the Canadian consciousness as all were confronted by the horrors of genocide inflicted against Indigenous peoples by the colonial state and religious institutions. The Indigenous community knew the unmarked burials of residential school children existed. July 1st was shrouded in orange in protest of nationalism and Canada Day itself. The masses stood in solidarity with the families and communities affected by the Indian Residential Schools. Hopefully, there will be more and continued public space for acceptance and support for healing and reparation to our communities. Truth before reconciliation.

If you or a family member are Indigenous and need support, please reach out to the Indian Residential School Survivors and Family at 1-866-925-4419. The Indian Residential Schools Crisis Line is available 24-hours a day for anyone experiencing pain or distress due to their residential school experience.

Photo Credits

Duck Lake, SK – St. Michael’s IRS – Students with Fr. O Chalebois, omi, 1900-1910. Provincial Archives of Alberta, Edmonton, AB.

Duck Lake, SK, St. Michael’s, IKS, Dormitory. 1926. Provincial Archives of Alberta, Edmonton, AB.

Indian Boys of the Duck Lake Boarding School working on the new addition. 1900s. United Church of Canada, Toronto, ON.

Prince Albert Indian Residential School. IRSHDC. Accessed November 9, 2022. https://collections.irshdc.ubc.ca/index.php/Detail/entities/1174.

Prince Albert (SK) OB3628, Dates of Operation July 1, 1894 – June 30, 1997, Provincial Archives of Alberta, Edmond, AB. https://collections.irshdc.ubc.ca/index.php/Detail/entities/1174

Bibliography

Kaye, Frances W. Hold High Your Heads (History of the Métis Nation in Western Canada) by A.-H. De Tremaudan, and the Ballad of Alice Moonchild — and Others by Aleata E. Blythe, and the Overlanders by Florence McNeil, and the Seventh Day by Lewis Horne. Western American Literature 18, no. 3 (1983): 271–72. https://doi.org/10.1353/wal.1983.0043.

Logan, Tricia. 2020. “Métis Experiences at Residential School”. The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/metis-experiences-at-residential-school.

Marmon, Lee. Literature and Sources Review by, Lee Marmon – Metisportals.ca. Accessed November 9, 2022. http://metisportals.ca/metishealing/wp-content/uploads/2010/02/FINAL-REPORT-ON-MTIS-EDUCATION-AND-BOARDING-SCHOOL-LITERATURE-AND-SOURCES-REVIEW-edited-june-15.pdf.

Niessen, Shuana. Shattering The Silence: The Hidden History of Indian Residential Schools in Saskatchewan. 2017. ebook. Regina: Faculty of Education, University of Regina. Available Online: https://www2.uregina.ca/education/saskindianresidentialschools/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/ShatteringthesilenceDuckLake8-16-2017.pdf.

Residential School Settlement Independent Assessment Process Final Reports. School Decisions. Accessed November 9, 2022. https://www.residentialschoolsettlement.ca/schooldecisions.pdf.

Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc, “Remains of Children of Kamloops Residential School Discovered,” May 27, 2021, media release, https://tkemlups.ca/remains-of-children-of-kamloops-residential-school-discovered/, accessed October 2, 2021.

De Trémaudan, Auguste Henri de. 1982. Hold High Your Heads: History of the Métis Nation in Western Canada. Translated by Elizabeth Maguet. Winnipeg: Pemmican Publications.

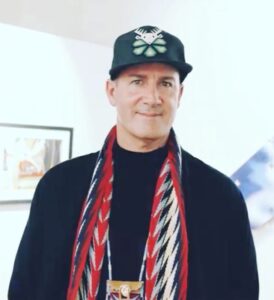

Jason Baerg is a registered member of the Métis Nations of Ontario and serves their community as an Indigenous activist, curator, educator, and interdisciplinary artist. Baerg graduated from Concordia University with a Bachelor of Fine Arts, a Master of Fine Arts from Rutgers University, and is enrolled in the Ph.D. program at Monash University. Baerg teaches as the Assistant Professor in Indigenous Practices in Contemporary Painting and Media Art at OCAD University. Exemplifying their commitment to community, they co-founded Shushkitew Collective and The Métis Artist Collective. Baerg has served as volunteer Chair for such organizations as the Indigenous Curatorial Collective and the National Indigenous Media Arts Coalition. As a visual artist, they push digital interventions in drawing, painting, and new media installation. Select international solo exhibitions include Canada House in London, UK, the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology in Australia, and the Digital Dome at the Institute of the American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA. They have sat on numerous art juries and won awards through such facilitators as the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario Arts Council, and The Toronto Arts Council. For more information about their practice, please visit JasonBaerg.ca

Jason Baerg is a registered member of the Métis Nations of Ontario and serves their community as an Indigenous activist, curator, educator, and interdisciplinary artist. Baerg graduated from Concordia University with a Bachelor of Fine Arts, a Master of Fine Arts from Rutgers University, and is enrolled in the Ph.D. program at Monash University. Baerg teaches as the Assistant Professor in Indigenous Practices in Contemporary Painting and Media Art at OCAD University. Exemplifying their commitment to community, they co-founded Shushkitew Collective and The Métis Artist Collective. Baerg has served as volunteer Chair for such organizations as the Indigenous Curatorial Collective and the National Indigenous Media Arts Coalition. As a visual artist, they push digital interventions in drawing, painting, and new media installation. Select international solo exhibitions include Canada House in London, UK, the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology in Australia, and the Digital Dome at the Institute of the American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA. They have sat on numerous art juries and won awards through such facilitators as the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario Arts Council, and The Toronto Arts Council. For more information about their practice, please visit JasonBaerg.ca