WE CALL

by Cathy Busby

Beginnings: Public Apologies

In the early 2000’s I began following the emerging media spectacle of public apologies coming from the mouths of CEOs, politicians, sports stars and others. Some of these apologies were of major historical significance while many were salacious in nature and of little public consequence. My work aimed to distinguish what was important from what was not in this blur of fleeting media moments.

This has led me to create work that straddles a space supporting Indigenous self-determination and interrogating state-driven reconciliation by interrupting media paradigms and steering news stories towards narratives that highlight critical voices. I wanted to extend the presence and messages of the landmark apologies for the Stolen Generations and the Indian Residential School (IRS) system made by the Prime Ministers Kevin Rudd of Australia and Stephen Harper (above) of Canada respectively in 2008. We Are Sorry, Melbourne (2009) and We Are Sorry, Winnipeg (2010) commemorated and compared these two historically consequential apologies. I put them in the public eye at a scale that would compete with large-scale outdoor advertisements. My 100-ish word versions in large Helvetica lettering were laid out on backgrounds of slightly different shades of pink derived from photos of the facial skin colours of each man. The Melbourne version was made of outdoor commercial sign vinyl and the Winnipeg version of industrial sign fabric. Exhibiting them put me in close contact and in some cases, working relationships with those who had thought long and hard about the apologies to the Stolen Generations and IRS survivors in Australia and Canada. As part of the Melbourne work, I made a documentary with  Indigenous filmmaker Daniel King in which I interviewed five diverse Indigenous leaders WE ARE SORRY (Daniel King, director/camera/editor, 2010) [1]. We talked about the value of the two apologies as well as the process and space for reconciliation.

Indigenous filmmaker Daniel King in which I interviewed five diverse Indigenous leaders WE ARE SORRY (Daniel King, director/camera/editor, 2010) [1]. We talked about the value of the two apologies as well as the process and space for reconciliation.

I focused on the 2008 Canadian apology when the federal government cut the budgets of a number of key Indigenous organizations, directly contradicting the apology that stated it was joining the recovery journey of Indigenous peoples. I designed a billboard titled, BUDGET CUTS, Saskatoon, 2012 at Paved and AKA Artist Centres in Saskatoon, and followed that with a limited edition silkscreen print by the same title to live on permanently, marking those historical budget cuts[2].

Accountability: Towards the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada Calls to Action

The following year, I made a more critical version of WE ARE SORRY, Witnesses, Vancouver, 2014: Art and Canada’s Indian Residential Schools[3]. A large fragment from Melbourne filled a wall between two ground-floor elevators and take-away fragments were available for visitors to have as a reminder of the now seemingly hollow 2008 apology. At the time, it seemed important to re-purpose my work to point out the inertia of the federal government.

After Witnesses, artist and hereditary Chief from the ‘Na̱mg̱is First Nation, Beau Dick, a colleague and studio neighbour, asked if he could have the large piece of WE ARE SORRY from Melbourne for Awalaskenis II: Journey of Truth and Unity, a Caravan that would take place in July 2014. I was happy to comply. The journey culminated in a copper-breaking ceremony on Parliament Hill in Ottawa performed to draw attention to the federal government’s lack of follow-through on the promises of Truth and Reconciliation, embedded in the 2008 apology. We Are Sorry provided a ground-cover and framework for the pounding of the copper, and then a wrapping for a broken piece, solemnly left on the steps of the Parliament Building’s Centre Block.[4]

In 2016 an exhibition commemorating this Caravan titled Lalakenis/ All Directions: A Journey of Truth and Unity was held at the Belkin Art Gallery. The exhibition documented the journey and also became a forum for Indigenous solidarity; a celebratory space, with performances and gatherings, while summarizing and historicizing the previous year’s on-the-road activism. For this context, Chief Dick asked if I would make a large panel with the entire edited apology, as opposed to the large fragment I provided for Awalaskenis II. This panel became a framing device and ground cover for an array of cultural belongings and delineated a space of Indigenous sovereignty. Awalaskenis II pre-dated the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action but was itself a call to action, and where a primary function of Awalaskenis II was to interface with the news media, Lalakenis was able to reverberate this call in the more private and ceremonial space of the University’s public art gallery exhibition.

In 2016 an exhibition commemorating this Caravan titled Lalakenis/ All Directions: A Journey of Truth and Unity was held at the Belkin Art Gallery. The exhibition documented the journey and also became a forum for Indigenous solidarity; a celebratory space, with performances and gatherings, while summarizing and historicizing the previous year’s on-the-road activism. For this context, Chief Dick asked if I would make a large panel with the entire edited apology, as opposed to the large fragment I provided for Awalaskenis II. This panel became a framing device and ground cover for an array of cultural belongings and delineated a space of Indigenous sovereignty. Awalaskenis II pre-dated the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action but was itself a call to action, and where a primary function of Awalaskenis II was to interface with the news media, Lalakenis was able to reverberate this call in the more private and ceremonial space of the University’s public art gallery exhibition.

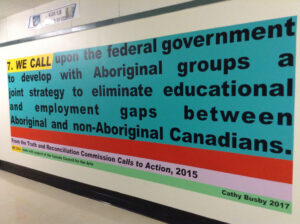

The forming of the TRC was one of the negotiated outcomes of the 2008 apology, and after six years documenting the testimony of over 6,750 witnesses, Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future, its final report, was published in 2015.[5] Included in the report were ninety-four Calls to Action, concrete steps to be implemented in all levels of infrastructure and institutions from schools and universities, to medicine, justice, and the media.[6] The Calls are a powerful guide for how to respond to this testimony through action and for bringing about concrete systemic change in the relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people and institutions.

Then and Now

Then and Now

As I was creating work in dialogue with this apology and following the work of the TRC, I was also re-evaluating a formative year of my life, 1974–75, as a white settler student at the Carcross Community Education Centre (CCEC), an ‘alternative’ high school housed in a former IRS. The daughter of progressive church leaders and political activists of English and Scottish stock, I made the move north when I was sixteen years old from the suburbs of Mississauga to the CCEC on the outskirts of the predominantly Tagish and Tlingit village of Carcross, Yukon.

Prior to its revamping as an alternative school in 1970 by a group of young educators and idealists, the site had housed the Chooutla, then Carcross, Indian Residential School from 1911–1969. In its new life as the CCEC, the Centre was an innovative and progressive educational experiment attracting young people mainly from Canada’s urban south, and nicknamed, ‘the hippie school’. While a number of the Indigenous students at the CCEC had also been students when it was an IRS, as non-Indigenous students and staff, we had little awareness of the IRS policies or their severe negative, sometimes deadly, impact on its students. For the approximately 80% non-Indigenous student body, the underlying damage of the CCEC’s former life was only felt as a faint undercurrent that was never directly addressed.

The IRS system, extending from the Indian Act’s intention to assimilate, or “kill the Indian in the child…” [7] was cruel and immeasurably harmful, identified by the TRC as “cultural genocide.” [8] It’s difficult to fathom that we non-Indigenous community members lived side-by-side with those who had suffered within that system, some in that very building. Though there was plenty of warmth and laughter between all of us, the silence on this subject led to a naive complicity with the colonial system on the part of non-Indigenous students and staff.

The TRC has created a hard-won resource from which we must listen and to learn; we settlers cannot claim ignorance anymore. As we remove our blinders, we must work to empower the next generations to learn the history of these lands, to keep them from complicity, and encourage them to be critically invested and involved in processes requiring substantial local and federal change. The immense work Indigenous individuals and communities have done to bring the truth of the IRS system to light and the potential of the TRC’s work to reshape our cultural and educational institutions is a starting point for me as an artist to listen, connect, think, learn, write and make art to contribute to the groundswell of Indigenous resurgence and revitalization. WE CALL is anchored in these reflections.

WE CALL, SFU: The Teck Gallery, Simon Fraser University Galleries (SFU), 2017 – 2018

I developed this work with curator Amy Kazymerchyk with the support of director Melanie O’Brian. Amy and I had meetings with a number of predominantly Indigenous faculty and staff at SFU who were well-aware of the Calls to Action and were improving resources and options for Indigenous students across the University’s disciplines.[9] We wanted to know if and how the Calls to Action were being activated in departmental structure, pedagogy and curriculum. We wanted to investigate how SFU Galleries could make space, start dialogue, and chart new pathways for cross-departmental communication and action that could help re-shape the infrastructure of the institution. These faculty and staff enlightened us on the complex long-term endeavours many were engaged in and the many initiatives that were underway in the university. We were humbled to learn how much was already happening as we considered how SFU Galleries could contribute to these initiatives. This investigation and these conversations were all part of the WE CALL project.

I make art that fills available space, often in dialogue with surrounding communities and existing architecture.[10] WE CALL is composed of abridged selections from the Calls addressed to post-secondary and cultural institutions. To maximize impact, each Call is printed in a distinct colour. Through the patterning and repetition of the yellow and black WE CALL refrain, the colours of cautionary road signs, the ten selected Calls emphasize the ways that the government is called upon by the TRC to cultivate Indigenous leadership, stewardship and participation within educational and cultural institutions and organizations.

I make art that fills available space, often in dialogue with surrounding communities and existing architecture.[10] WE CALL is composed of abridged selections from the Calls addressed to post-secondary and cultural institutions. To maximize impact, each Call is printed in a distinct colour. Through the patterning and repetition of the yellow and black WE CALL refrain, the colours of cautionary road signs, the ten selected Calls emphasize the ways that the government is called upon by the TRC to cultivate Indigenous leadership, stewardship and participation within educational and cultural institutions and organizations.

The Teck Gallery has no doors, attendant or gallery hours. It’s located at the end of a foyer with two large walls that face each other and frame a large window that overlooks Vancouver’s North Shore. It’s a location where people often sit down to study or eat lunch. I envisioned WE CALL working with this openness and liminality. The work was installed as two parallel floor-to-ceiling wall-text paintings facing one another across the space. The location was ideal for hosting WE CALL, this impermanent public commemorative artwork, that would be in place for a year and be an occasion for related conversations and gatherings.

In the Fall of 2017 during its display, we brought together an SFU Galleries’ advisory group of four Indigenous women[11]. I had fabric replicas of the wall paintings made for these meetings, which were held in SFU Gallery at the Burnaby campus, far from the Teck Gallery’s location. The panels were printed at three-quarter scale as a portable version that could be put up quickly and easily with velcro fasteners, installed to complement discussions about what SFU Galleries could do to align with the Calls.[12] We hosted two gatherings, during which we shared food and discussed questions including: What are the barriers keeping Indigenous people from participating in contemporary art at SFU? What are the most important qualities of hospitality at an event such as childcare, food, a welcoming attendant, seating comfort, accessibility, scheduling? What outreach strategies could we use to connect with audiences who are not already part of a contemporary art community? If it’s a question of in-reach, of personnel and artwork going to another location or community space, what are protocols to consider? What are concrete ways of supporting economic justice within contemporary art? What does having these conversations in an art gallery lend to the bigger conversation?[13]

In the Fall of 2017 during its display, we brought together an SFU Galleries’ advisory group of four Indigenous women[11]. I had fabric replicas of the wall paintings made for these meetings, which were held in SFU Gallery at the Burnaby campus, far from the Teck Gallery’s location. The panels were printed at three-quarter scale as a portable version that could be put up quickly and easily with velcro fasteners, installed to complement discussions about what SFU Galleries could do to align with the Calls.[12] We hosted two gatherings, during which we shared food and discussed questions including: What are the barriers keeping Indigenous people from participating in contemporary art at SFU? What are the most important qualities of hospitality at an event such as childcare, food, a welcoming attendant, seating comfort, accessibility, scheduling? What outreach strategies could we use to connect with audiences who are not already part of a contemporary art community? If it’s a question of in-reach, of personnel and artwork going to another location or community space, what are protocols to consider? What are concrete ways of supporting economic justice within contemporary art? What does having these conversations in an art gallery lend to the bigger conversation?[13]

Funding from the Canada Council provided an opportunity to expand upon work developed through WE CALL, SFU with the Gitxsan Wet’suwet’en Education Society (GWES) College in Hazelton, BC (2017). The installation at the Teck Gallery concluded in April 2018 with a summary event including a panel of Indigenous and non-Indigenous speakers from both GWES and SFU[14].

Gitanmaax/Hazelton

The confluence of the Skeena and the Bulkley Rivers has been the abundant life-giving source and centre of the Gitxsan Nation with archeological proof of habitation going back 10,000 years[15]. Contact was late to this part of British Columbia, coming with the fur trade in the 1850s and the launch of a Hudson’s Bay trading post in 1856 in what is now the Gitanmaax/Hazelton townsite. However, the IRS system was forced on the Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en Nations in the 1920s by an amendment to the Indian Act.

The Nations of this area have a history of resilience and resistance through political action from shortly after contact into the 21st century.[16] Blockades have been effective tactics used since at least 1872, when Gitsegukla Chiefs blockaded the Skeena River halting traffic to demand compensation after European prospectors burned down Gitxsan settlements. In 1988–89, a huge protest successfully ended the helicopter-spraying of the herbicide glyphosphate used in the forestry industry. Forestry incited protest again in the 1990s, with excessive logging north of Kispiox resulting in a peaceful protest that successfully decreased the rate of logging in the area. Another important gain of national significance came in 1997 from the Supreme Court of Canada in Delgamuukw Gisdaywa v. the Queen, an historic ruling that contained the first comprehensive account of Aboriginal title in Canada, and established adaawk, oral testimony, as a form of testimony on par with conventional written statements.  Commitment to resistance and sovereignty is continued most recently in the Wet’suwet’en land claims and blockades on the CN rail lines in early 2020, in response to the Coastal GasLink pipeline expansion crossing unceded territory.

Commitment to resistance and sovereignty is continued most recently in the Wet’suwet’en land claims and blockades on the CN rail lines in early 2020, in response to the Coastal GasLink pipeline expansion crossing unceded territory.

In the townsite surrounding the rivers, Gitsanimx is a living language taught to the young people at home, in schools and at the daycare centre. Among Indigenous and some non-Indigenous people, common phrases and words are in daily use as this revival takes hold and spreads. However, the legacy of colonization is palpable and ongoing.

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP) was signed by Canada in 2010 and the BC government legislated its implementation in November 2019, the first province in the country to do so. However, in July 2020, the Supreme Court of Canada threw out the Wet’suwet’en appeal that they had not been meaningfully consulted on the expansion of the Coastal GasLink pipeline.

At the time of this writing, the Wet’suwet’en fight for land rights and the resistance to corporate overstep and intrusion continues.

WE CALL: Gitxsan Wet’suwet’en Education Society (GWES) 2016 – 2017

My brother Andrew Busby, taught at the Gitxsan Wet’suwet’en Education Society (GWES) in Gitanmaax/Hazelton 2015 – 2020. He and his wife Bev Busby have lived and worked there for over thirty years. Andy’s known in the community for taking people dog mushing in the winter and is the guy everyone calls to clean their freezers of unwanted fish and game, which he feeds to his twenty-or-so dogs. I suggested doing a version of WE CALL in Gitanmaax/Hazelton to Andy and Bev.  We thought GWES would be an ideal location as a centrally located Indigenous-run educational institution with plenty of wall space and a progressive agenda. Founder and then Executive Director, Chief Marjorie McRae enthusiastically approved and with the agreement of the rest of the staff, I was invited to do the work.[17]

We thought GWES would be an ideal location as a centrally located Indigenous-run educational institution with plenty of wall space and a progressive agenda. Founder and then Executive Director, Chief Marjorie McRae enthusiastically approved and with the agreement of the rest of the staff, I was invited to do the work.[17]

GWES is housed in the former Hazelton Amalgamated School that opened in 1951[18]. It was one of the first integrated high schools in the province and is on land given in trust by Gitxsaan Chief Ben MacKenzie on condition that there would be a school operating on the property. It closed with the opening of the new Hazelton Secondary School in the early 1990s, with GWES taking over the building soon after. It’s attended almost exclusively by Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en students and is a place where people go to complete high school, for job training, or for further education.[19]

GWES is housed in the former Hazelton Amalgamated School that opened in 1951[18]. It was one of the first integrated high schools in the province and is on land given in trust by Gitxsaan Chief Ben MacKenzie on condition that there would be a school operating on the property. It closed with the opening of the new Hazelton Secondary School in the early 1990s, with GWES taking over the building soon after. It’s attended almost exclusively by Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en students and is a place where people go to complete high school, for job training, or for further education.[19]

After speaking with students and staff, we decided to locate WE CALL in the most heavily trafficked areas: just inside the main entrance and along the main corridor, above a long bank of lockers, and in the administrative hallway. On entering the school, two wall text paintings include Calls addressing historical promises of equity on one side, and economic opportunity and justice on the other. Further into the building, the Calls are about alternatives to imprisonment and reducing the number of children in care. The Calls we chose and edited for the space were in response to lived experiences of the Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en communities.

Tragically, after WE CALL was approved, Chief Marjorie McRae died suddenly in August 2016. Though I never met her, I know she strongly believed in the work of the TRC and the Calls to Action. I decided to make the colours be a tribute to her. I was told that she wore a lot of purple, so I used light and dark purple, and that she liked green, like the green of the forest and springtime; she was fond of verdigris, the colour copper turns when it oxidizes; the orange colour of the salmon; and red, a traditional Gitxsan colour. The administration hallway where her office had been became the placement for a Call to Action that spoke to Chief McRae’s commitment to education and was nicknamed, ‘The Marj Wall’, a tribute to her legacy.

Painting often took place while programming and classes were in session, and we were cheered on by students and staff with comments such as, “It’s like you’re tattooing the wall!” and “These walls need some love.”

Momentum to celebrate the work gathered as it neared completion. Staff decided to organize a late morning gathering followed by a luncheon to launch WE CALL at GWES in December 2017. The event was attended by the GWES Board of Directors and notable Gitxsan and non-Indigenous community members. A number of us spoke, including local Elder Shirley Muldoe who stressed the importance of the language, speaking in Gitsanimx. The Board presented me with a bentwood box with a hummingbird delicately painted on it by local artist Kendel Mowatt. In the gifting, I was told that the hummingbird is a messenger, and I was thanked for my message of WE CALL. This heartfelt appreciation was something I’d never before experienced in my art career. The work was intended as a six-month installation, however acting Director Kirsten Barnes and other staff members asked that it remain permanently, and I happily agreed.[20]

WE CALL: Upper Canada College (UCC), Toronto, 2018

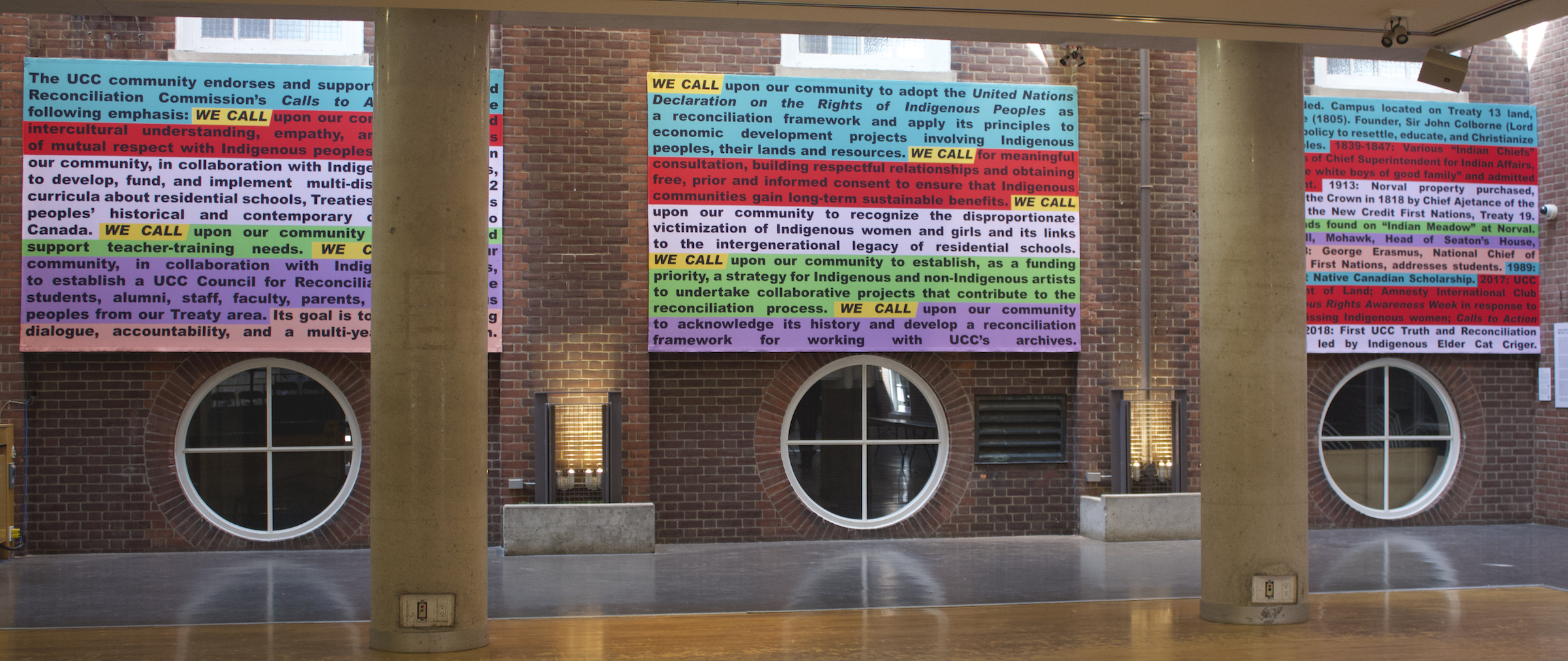

I was invited to UCC after members of their Amnesty International Club saw online images of WE ARE SORRY at the Belkin Art Gallery (2012). Vesna Krstich, a visual arts and theory of knowledge teacher, as well as the Club’s faculty supervisor, contacted me to see if I would be interested in working with them on an art project in this vein. This is a prestigious independent school in a major city where many students actively benefit from the status quo, whereas the systemic barriers affecting those at GWES, a school on the margins both economically and geographically, mean students succeed in spite of the system. I was heartened that UCC had this Club and that its members wanted to contribute to justice for Indigenous peoples. In a phone call with Vesna I introduced my recent WE CALL work and said that I thought there’d been enough apologizing and that it was time for action. This propelled the Club to pursue a Calls project.[21]

I spoke with the students through a series of lunchtime video calls. We discussed the Calls to Action document and they determined that issues pertaining to schooling and education were the most relevant for them. The Club addressed the Calls with the UCC community by hosting a Circle for Reconciliation meeting in January 2018. The meeting consisted of current students, faculty, members of senior leadership, alumni, and was led by Elder Cat Criger, who has guided UCC with their reconciliation efforts on various occasions. Toward the end of the process of selecting Calls, the group decided to address them from the UCC community. Their version begins each Call, “We call upon our community…” This was a way of taking ownership, making a commitment to hold their institution accountable, a sentiment further reflected by the selected Calls. The group also decided that with the help of the school’s archivist, Jill Spellman, that the third, of the three WE CALL panels, would be a timeline highlighting UCC’s relationships with Indigenous peoples since its beginnings in 1829.

We considered indoor and outdoor locations, and I decided that of all the options, the most prominent and interesting space was the former exterior wall of an older building incorporated through a renovation into a new interior atrium-like gathering space joining two buildings. It’s known informally as the Student Centre and serves as the creative hub of the school. The panels were printed on poly-duck fabric, attached to stretchers and nested into the window wells. The palette was the same as at GWES, thus twinning the projects in colour and carrying forward the tribute to Chief Marjorie McRae.

UCC’s Truth and Reconciliation Week in April 2018 was organized as parallel programming to WE CALL. I spent those five days meeting with students and staff, and arranging and troubleshooting the installation. The week was launched with a talk by Gerald McMaster, curator, artist, author, and professor of Indigenous Visual Culture and Critical Curatorial Studies at the Ontario College of Art and Design University, and a Plains Cree member of the Siksika Nation; and at the end of the week, closed by Barry Hill, a former mechanical engineer, commercial farmer, amateur historian, a Mohawk member of the Six Nations of the Grand River, and alumnus of UCC.[22] On the last day, WE CALL was launched with a land acknowledgement and smudging ceremony led by Elder Cat Criger. I gave a talk connecting this work with the GWES and SFU versions. In the following months, the school created what is now recognized as a hallmark of the project – the UCC Council for Reconciliation with the WE CALL panels serving as the mandate.

UCC Visits GWES and Gitanmaax/Hazelton, 2022

Four years on, in January 2022, Vesna Krstich asked and I agreed to facilitate a two-day student-visit to Gitanmaax/Hazelton. She initially proposed the idea to her colleague, Tom Babits[23] who was already planning a school trip to BC tailored around Indigenous education[24]. Vesna and I had spoken in 2018 about making a connection between the two schools when the time was right and given that Tom was planning this trip, that the time was now. The UCC group wanted to see the WE CALL work at GWES and hoped to meet Gitxsan students. My brother connected us with Hazelton Secondary School (HSS), where he now taught, and with Patty Rubinato, a Gitxsan teacher and GWES vice-principal. Patty advised and organized. Our planning group was joined by Vlad Chindea and Shaan Hooey, alumni who’d been instrumental as students in realizing WE CALL at UCC. Jyoti Sehgal, UCC’s Horizons Director, joined our planning circle. She lead educational activities including video calls between students from both schools before the trip. Barb Janzee, HSS Principal was supportive, and grade eleven Gitxsan student Shanna McCarthy had ideas for bringing her fellow students on board. UCC student, Daniel McDonald joined and reminded us how sport can be a great way of connecting youth. Over our weekly online calls between Gitanmaax/Hazelton, Vancouver and Toronto, we imagined various art and cultural encounters and the itinerary puzzle gradually came together.

The two groups met in person on National Indigenous People’s Day, June 21, 2022. The UCC group of twenty-five arrived to a complimentary lunch that began with a Gitsanimx welcome and blessing from one of the cooks. The cafeteria was overflowing with students and a buzz of enthusiasm, setting a tone of immediate camaraderie. The students spontaneously headed to the gym right after lunch to play basketball and volleyball, something they would plan among themselves to do again the next day.

Along with meeting other young people, our itinerary included seeing art and meeting Gitxsan artists. From HSS, we drove to the nearby ‘Ksan Historical Village and Museum, owned and operated by the Gitanmaax Band, where traditional pole carver Dan Yunkws would share his craft at his studio, formerly the Gitanmaax (Kitanmax) School of Northwest Coast Art. Students not only watched and listened, but were able to try their hand at making a few cuts on this house pole with Dan’s guidance, the smell of cedar in the air. While at ‘Ksan, we joined in the Indigenous Day unveiling of two pole carvings Dan had recently completed at either side of the new Ceremonial Arbor, an outdoor performance stage on the grounds. We joined in with the several hundred locals assembled for this late afternoon celebration and enjoyed the Gitxsan Thunder Drummers, the ‘Ksan dancers, and the free t-shirts and burgers.

The second day started with UCC and HSS students at GWES walking the central corridor, stopping to read and consider each of the Calls along the way. A different student read each one and then talked about its relevance. After the reading of “We call upon the federal, provincial, territorial, and Aboriginal governments to commit to reducing the number of Aboriginal children in care,” Patty Rubinato explained how she is the guardian of her nephew’s three young children, who would otherwise be without parents or guardians, and the importance of keeping children out of government care and with family and community. Her personal story brought life to the Calls.

From WE CALL at GWES, we bussed to Date Creek Road where land defender Kolin Sutherland-Wilson and his family have been protecting their traditional territory from unauthorized logging over the past 18 months. Kolin greeted and led us up a gravel road to a fire tended by two elders, and other campers, including Della, who spent the winter there in a canvas tent with a plank floor and wood stove. A short walk away, another family member, artist and art educator Arlene Ness, spoke to the group. We were welcomed like old friends, with good humour, fresh barbequed salmon, and conga-line-like dancing. Then Kolin led a walk along the edge of the forest and spoke of land protection in relation to the breaking of the Royal Proclamation of 1763, Treaty of Niagara of 1764 and UNDRIP’s requirement of ‘free, prior and informed consent.’ We’d discussed these documents earlier that morning as part of WE CALL at GWES. To hear Kolin speak of them here on the land helped connect the Calls to Action to these land-protectors defiance in protecting the old growth forest from logging.

From WE CALL at GWES, we bussed to Date Creek Road where land defender Kolin Sutherland-Wilson and his family have been protecting their traditional territory from unauthorized logging over the past 18 months. Kolin greeted and led us up a gravel road to a fire tended by two elders, and other campers, including Della, who spent the winter there in a canvas tent with a plank floor and wood stove. A short walk away, another family member, artist and art educator Arlene Ness, spoke to the group. We were welcomed like old friends, with good humour, fresh barbequed salmon, and conga-line-like dancing. Then Kolin led a walk along the edge of the forest and spoke of land protection in relation to the breaking of the Royal Proclamation of 1763, Treaty of Niagara of 1764 and UNDRIP’s requirement of ‘free, prior and informed consent.’ We’d discussed these documents earlier that morning as part of WE CALL at GWES. To hear Kolin speak of them here on the land helped connect the Calls to Action to these land-protectors defiance in protecting the old growth forest from logging.

As Jyoti Sehgal, Director, Horizons at UCC wrote afterwards:

A meaningful moment is most certainly the time of being at the old-growth forest, welcomed in with singing and drumming, followed by a sharing of the meaning of the land, and the impact of corporate behaviours which have decreased salmon spawning in the river. Hearing Kolin Sutherland-Wilson orient our knowing/unknowing with learning/unlearning has stayed with me; I will not forget sharing a meal, walking together, and hearing valuable, perhaps life-impacting, perspectives. I feel such deep gratitude to have been invited in so beautifully and trusted or considered a valid audience for the sharing of their family’s history of the land, the taking of the land, as well as the limitations of recourse. (Sehgal, 2022)

With full bellies, the smell of lingering wood smoke, and much to ponder, we got back on the bus and headed to Kispiox. There Gitxsan guide, Larry Vance gave an overview of the historic house poles, that function to tell stories of the Gitxsan people who have lived here for millennia. We then drove to the state-of-the-art Upper Skeena Valley Recreation Centre, where students saw Gitskan artist Michelle Stoney’s massive recently-completed mural spanning the interior of the building describe the townsite. Alex Stoney, her brother, assistant, and business manager, spoke to us about the process of installing the work. Both Stoney’s contemporary formline mural and the more traditional carving of Dan Yunkwz, the carved house panels in ‘Ksan to the weathered poles in Kispiox provided an immersion into the rich and longstanding art and cultural forms of the area.

The two days went by quickly, and to close the visit back at GWES, Patty with her teenaged son, Matt, prepared a feast, including moose meat; a dish of herring roe on kelp; and locally harvested berries. There was a chance for anyone to speak and share insights and thanks.

From alumnus Shaan Hooey:

…Though it was only two days, I leave with a feeling in my heart that this is but the start of a wonderful chapter in which UCC and Hazelton students can grow alongside one another in their journeys through school and beyond. There is no ‘other’ anymore: as Patty [Rubinato] so eloquently shared, my story is a part of yours, as yours is a part of mine. (Hooey, 2022)

From Monika Mai Kastelic, teacher, UCC:

I do not have adequate words to describe the connections, transformations, healing, education, unlearning, learning and heartfelt discussions and laughter that occurred over the trip. It was the most important trip that I have ever gone on as an adult. (Kastelic, 2022)

From Shanna McCarthy, HSS student:

The tour of GWES was very special as UCC learned a lot and the students got to experience a feast there later. Both UCC and HSS students wanted to learn more about each other. This short visit has opened many doors and is a beginning to a great friendship between two very different and diverse schools. We did not realize how rare it is to have such a close knit and supporting community as ours. (McCarthy, 2022)

My facilitation role with this project has come to an end. My hope is that these newly forged relations continue.

WE CALL: CONNECTIONS, COMMEMORATION AND CONTINUITY

The TRC worked tirelessly to witness accounts of former students in the IRS system, write a comprehensive 528-page report, and put forward the Calls to Action. They proposed an ambitious systemic overhaul of the relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples and institutions in Canada. My work, WE CALL came from the desire to amplify, mobilize and commemorate the work of the TRC, and to translate the dense document of the Calls to Action into life and public spaces using contemporary and conceptual art strategies.

Meaningful change requires ongoing engagement, and it is often within our educational and cultural institutions that this work is done and where powerful acts of change can build traction.

WE CALL is one answer to the question of how artists, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, can act as stewards of the history of these lands and help prevent a lapse backward into naive complicity with colonial practices. Through doing this work I was reminded that art is able to distill and communicate such messages and foster space to gather for learning, slipping across disciplines and borders in a way that contributes to new networks of relationship and action.

Each version of WE CALL is an abbreviation referencing the entire 94 Calls to Action through SFU’s, GWES’s, or UCC’s specific lens. Within such different milieus, I imagine different forms of ownership, and response to both the artwork and the Calls themselves. How does seeing this large, colourful text work affect the students’ and other viewers’ relationship to the Calls and to reconciliation? Art is uniquely able to transpose, in this case from document to wall-text to discussion, commemoration and action. WE CALL interprets commemoration as both a pause to celebrate and to honour the work of the TRC, which it does with its choice of locations, bold colours, scale, and specificity of Calls. It also seeks to create action towards on-going nation-to-nation relationships.

Cathy Busby, April 29, 2024

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Busby, Cathy. Sorry, 2nd edition, Halifax: Saint Mary’s University Art Gallery with Sydney, Australia, College of Fine Arts, University of New South Wales, 2007.

Busby, Cathy. We Are Sorry. pamphlet, Vancouver: Belkin Art Gallery, UBC, 2013.

Gitxsan.com. “History of Resistance”, page accessed Dec 2020, http://www.gitxsan.com/culture/culture-history/gitxsan-history-of-resistance

Griffin, Kevin. “Lalakenis Recounts the Journey that Shamed the Federal Government,” Vancouver Sun, January 14, 2016, https://vancouversun.com/news/staff-blogs/lalakenis-recounts-indigenous-journey-that-shamed-the-federal-government

Harding, John. “We Are Very Sorry,” in Site Unseen, Georgia Sedgwick, ed, Laneway Commissions, Melbourne, 2009.

Harper, Stephen. “Statement of apology to former students of Indian Residential Schools” Government of Canada, June 11, 2008. https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100015644/1571589171655

Hart, Sydney and Little, Clay, eds. Journeys in Weaving Histories, Vancouver: First Nations Student Services at Capilano University and Presentation House Gallery, 2015.

Hooey, Shaan. Email, 2022.

Kastelic, Monika Mai. Email, 2022.

McCarthy, Shanna. Email, 2022.

Sehgal, Jyoti. Email, 2022.

Switzer, Maurice, ed, “Big Numbers Hide Huge Failures…,” featuring image of Budget Cuts, Paved Arts/AKA Artist-run Gallery, Saskatoon, in Anishinabek News, Union of Ontario Indians, North Bay, Canada, Oct 2012.

Troian, Martha.“Copper Broken on Parliament Hill in First nations Shaming Ceremony”, CBC, July 27, 2014

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. 2012. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Winnipeg: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.

http://nctr.ca/assets/reports/Final%20Reports/Executive_Summary_English_Web.pdf

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. 2015. Truth and Reconciliation: Calls to Action. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/british-columbians-our-governments/indigenous-people/aboriginal-peoples-documents/calls_to_action_english2.pdf

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. 2015 Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. http://nctr.ca/assets/reports/Final%20Reports/Executive_Summary_English_Web.pdf

United Nations (General Assembly). 2007. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People.

(Article 32 [II]) https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2018/11/UNDRIP_E_web.pdf

Watson, Scott, and Brown, Lorna, curators. Lalakenis/All Directions: A Journey of Truth and Unity. Vancouver: Belkin Art Gallery, 2016.

CAPTIONS

Fig 1. Cathy Busby, SORRY (Stephen Harper), Sorry series inkjet prints, 2009. Photo: Cathy Busby

Fig 2. Cathy Busby, Budget Cuts, 2012, billboard, AKA Gallery+Paved Arts, Saskatoon. Photo: Bart Gazzola

Fig 3. Cathy Busby, We Are Sorry in Awalaskenis II: Journey of Truth and Unity, vinyl fragment, 2014. Photo: Franziska Heinze

Fig 4. Students and staff on steps of Carcross Community Education Centre (CCEC), 1975. Photo: unknown

Fig 5. Cathy Busby, WE CALL, 2017, installation view, Teck Gallery, Harbourfront Centre, Simon Fraser University 2017. Photo: Blaine Campbell

Fig 6. Cathy Busby, WE CALL, 2017, installation view, Teck Gallery, Harbourfront Centre, Simon Fraser University 2017. Photo: Blaine Campbell

Fig 7. WE CALL, fabric version, preparing for Advisory Group meeting, Simon Fraser University Gallery, Burnaby, BC, 2017. Photo: Cathy Busby

Fig 8. installing fabric version of WE CALL, Simon Fraser University Gallery, Burnaby, BC, 2017. Photo: Karina Irvine

Fig 9. Opening gathering for WE CALL: GWES, Gitanmaax/Hazelton, BC, Dec 2017. Photo: Nikita Campbell

Fig 10. Cathy Busby, WE CALL: GWES, 2017, installation view, main entrance and foyer, Hazelton, BC, Photo: Nikita Campbell

Fig 11. Cathy Busby, WE CALL: GWES, 2017, installation view, administrative hallway, Gitanmaax/Hazelton, BC, Photo: Nikita Campbell

Fig 12. Cathy Busby, WE CALL: GWES, 2017, installation view, main hallway, Gitanmaax/Hazelton, BC, Photo: Nikita Campbell

“We Call on the federal, provincial, territorial, and Aboriginal governments to commit to reducing the number of Aboriginal children in care.”

Fig 13. Cathy Busby, WE CALL: GWES, 2017, installation view, main hallway, Gitanmaax/Hazelton, BC, Photo: Nikita Campbell

“We Call upon governments to provide sufficient funding to implement community alternatives to imprisonment for Aboriginal offenders and respond to underlying causes.”

Fig 14. Cathy Busby, WE CALL: Upper Canada College, 2018, installation view, enclosed courtyard, Upper Canada College (UCC), Toronto. Photo: Caley Taylor

Fig 15. Kolin Sutherland-Wilson speaking to students from UCC and HSS at Xsu Wil Masxwit Photo: Cathy Busby

[1] Sorry documentary interviews with Herb Patton, Vicky Walker, Nathan Lovett-Murray, Mick Edwards, John Harding. To view: https://danielcking.weebly.com/films.html. 26 mins.

[2] I also followed up with a multi-page page-work titled Cut and Muzzled listing further cuts made by the federal government at the time (Capilano Review, 3.23, 2014).

[3] Witnesses: Art and Canada’s Indian Residential Schools, Belkin Art Gallery, satellite space of at the Koerner Library at the University of British Columbia (UBC), Vancouver, BC, 2013

[4] This large fragment of WE ARE SORRY had travelled from the Melbourne, Australia, where it hung on the wall of a power substation for five years; was returned to Vancouver, Canada for an exhibition about Canada’s IRS system, and was now in Ottawa at the seat of federal power, at the Parliament Buildings where the apology had first been delivered in 2008.

Kevin Griffin, “Lalakenis Recounts the Journey that Shamed the Federal Government, Vancouver Sun, January 14, 2016, https://vancouversun.com/news/staff-blogs/lalakenis-recounts-indigenous-journey-that-shamed-the-federal-government

[5] Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. 2012. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada interim report. Winnipeg: Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.

http://nctr.ca/assets/reports/Final%20Reports/Executive_Summary_English_Web.pdf

[6] Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, United Nations, National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, and Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. 2015. Calls to Action. http://trc.ca/assets/pdf/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf

[7] Stephen Harper, “Statement of apology to former students of Indian Residential Schools” Government of Canada, June 11, 2008 https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100015644/1571589171655

[8] Truth and Reconcilliation Commission of Canada. Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Winnipeg, MB: Truth and Reconcilliation Commission of Canada, 2015. http://nctr.ca/assets/reports/Final%20Reports/Executive_Summary_English_Web.pdf

[9] Kazymerchyk invited me to exhibit at the Teck Gallery, one of three SFU galleries, this one located in the university’s Harbour Centre campus. Our first meeting was in Fall 2016 with William Lindsay, Director of the Office of Aboriginal Peoples, followed by Jeffrey Reading, Health Sciences; Brenda Morrison, Restorative Justice, Criminology; Veselin Jungic, Mathematics, February 2017; Annie Ross, Indigenous Studies; June Scudeler, Indigenous Graduate Support Services Coordinator; Marcia Guno, Director Indigenous Student Centre, March 2017.

[10] Variations on the wall-text painting are a recurrent form in my artistic practice along with compiling and editing ready-made lists and collections (Totalled, 2004; Branded, 2008; Inspiring, 2010; Sorry, 2002-2014; Steve’s Vinyl, 2011 / 2013; About Face, 2012). We Call builds on these strategies to make critical commentary through wall-text painting, providing printed matter to substantiate the work, and gathering audiences to respond to the issues at stake.

[11] Roxanne Charles, MFA graduate student, SFU; June Scudeler, Indigenous Graduate Student Support Coordinator and Sessional Instructor, SFU; Gabrielle L’Hirondelle Hill, Métis artist and writer; Annie Ross, faculty, SFU.

[12] These panels were later requested by the Art Museum at the University of Toronto for the exhibition I Continue to Shape (2018), guest curated by cheyanne turions, and the Art Gallery of Grand Prairie for their exhibition Sonic Youth (2019), curated by Derrick Chang.

[13] For more detail https://www.sfu.ca/galleries/teck-gallery/past1/CathyBusby-WE-CALL.html

[14] This panel brought these two iterations of the project into dialogue: Closing Reflections and Reception, April 19, 2018. WE CALL and its place within SFU Galleries’ structural operations and public programming with Cathy Busby, Amy Kazymerchyk, Advisory Committee members June Scudeler; Gabrielle L’Hirondelle Hill; and GWES staff Kirsten Barnes, Acting Director; Andrew Busby, Instructor; and Bonnie McCreery, Instructor at SFU Harbour Centre Segal Centre. Video: https://www.sfu.ca/galleries/teck-gallery/past1/CathyBusby-WE-CALL.html. Reflections were followed by a reception at the Teck Gallery.

[15] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gitxsan

[16] “History of Resistance”, Gitxsan, page accessed Dec 2020, http://www.gitxsan.com/culture/culture-history/gitxsan-history-of-resistance

[17] I also gratefully acknowledge support of the Canada Council for this work and the version at SFU.

[18] https://bcbooklook.com/neil-sterritt-an-under-heralded-gitxsan-hero/

“…In the upper grades children of all races from the surrounding villages attended the Hazelton Amalgamated School. The school was opened in 1951 by the Gitanmaax Band Council, the Hazelton Municipal Council, BC provincial officials and local residents and was reputed to be the only school of its kind in Canada.”

[19] “GWES has remained committed to working towards improving the educational and training outcomes of the populations they serve by delivering educational programming, implementing training initiatives, promoting self-reliance, and creating meaningful employment. As well, GWES is committed to the continued development and implementation of culturally relevant programs in areas such as Education, Social Services, Health, and Child Welfare.” https://gwes.ca/about-us/

[20] Thanks to Dave Lattie, Kathy Clay, and Andy Naylor and Andrew Busby and his spouse, Bev Busby for their hands-on help, along with my late spouse, Garry Neill Kennedy (d. 2021). Thanks to Patrick O’Neill for layout assistance and Brian Messina at Proper Design in Vancouver for cutting the sign vinyl. GWES staff, Patty Rubinato, Sharon Ness, Ashley Reagan, Bonnie McCreery, and Geminee Wilson took charge of the launch.

[21] As recalled by Vesna Krstich in an email, November 21, 2022.

Soon after the WE CALL project, student Robbie Evans, a member of Amnesty International Club, formed and led the Truth and Reconciliation Club.

[22] Further parallel programming that week also took place at UCC’s Norval Outdoor School, and included artist and OCAD University professor, Shannon Gerard and artist Brianna Tosswill creating and publishing a newspaper written and drawn by students, and distributed throughout the UCC community at the conclusion of the week. They worked with the Calls, school archives, and with Elder Gary Sioux to write new Land Acknowledgments for the Norval campus (which is Treaty 19, while Deer Park campus, Toronto, is Treaty 13). Senior students held other workshops and the Amnesty International Club displayed maps, photos, and notes that documented learning about local Indigenous history, traditions and contemporary political and social issues.

[23] Director of Community Service, Clubs, and the Creativity, Activity and Service (CAS) program

[24] This week-long trip would continue in Vancouver and Keremeos.

was born into a family of life-long social justice activists of Scottish, English and protestant descent and grew up in what was known to her as ‘Mississauga, Ontario’. She moved to Carcross, Yukon on her own as a teenager to be part of an alternative school and community, The Carcross Community Education Centre, housed in a former Indian Residential School (Chootla School), where 90 mainly non-Indigenous and Indigenous students, staff and teachers, learned and lived together.

was born into a family of life-long social justice activists of Scottish, English and protestant descent and grew up in what was known to her as ‘Mississauga, Ontario’. She moved to Carcross, Yukon on her own as a teenager to be part of an alternative school and community, The Carcross Community Education Centre, housed in a former Indian Residential School (Chootla School), where 90 mainly non-Indigenous and Indigenous students, staff and teachers, learned and lived together.

At the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design (BFA 1984), she made art and voiced her

concerns about women’s rights, including affordable housing, job equity, and the proliferation of militarism. After completing her MA in Media Studies and PhD in Communication (1999), she turned her critical eye back to long-term art-making and began gathering what became an extensive collection of public apologies. It was the 2008 apologies to Indigenous peoples by Canadian and Australian prime ministers that fuelled her 16-year body of work about reconciliation that increasingly engaged diverse communities.

She was a Fulbright Scholar at New York University (1995-96) researching pain and self-help culture (co-ed, When Pain Strikes, U of Minnesota Press, 1999), and later a contemporary art researcher at the National Gallery of Canada (1997-98) investigating representations of pain in the work of the artist trio, General Idea. She has been making installations, printed matter, performance, and exhibiting widely including in New York, Berlin, Beijing and Melbourne for the past four decades. She makes her home in Vancouver.

A Creative Conciliations Chapter