1. What inspired you to first start working with Native artists and Native art?

I’m a born and bred New Yorker, born in Brooklyn. I have a degree in art history. My first solid job was at Sotheby’s, the auction house. The department I got a job in handled all auctions areas: African, Pre-Columbian, Antiquities, Islamic and American Indian Art. That was in 1974 and at that time there were very few sales that included American Indian Art. Two major auctions that took place one in 1971 and 1972 of the Green collection, which included an important collection of baskets.

The department had a great library. I liked the material, and because of Sotheby’s location, we had very interesting people that came in and would talk about the work on the shelves. I took a liking to the people that were interested in Native art, in particular I liked the art, I liked baskets and beadwork. I asked if I could focus on Native Art, as a part-time to my regular job. I asked lots of questions and I took books home and then I ultimately became the first expert at Sotheby’s. I worked there for 25 years and focused solely on historic Native Art.

How did you classify historical material?

We considered everything that was pre-1920s. Ironically, whatever I looked at that was post-1920s, we would not even regard it. Towards the end of my career, we would occasionally include works by Southwest artists like Maria and Topovi in auctions. The real interest for people buying at auctions were unsigned works, the history, almost too much in the romance of the history, the anonymity of the work. Perhaps, this really pushed me to find work that is documented, contemporary, and by artists who have a point of view.

So many collectors did not want to know the artists; they wanted to know about the romantic history of the work.

I created the department of Native art. The first sale solely devoted to Native art was in 1976. At that time, it was amazing where things were, and how people treated and regarded things. So much has changed. That was before all these laws were put into place, well before NAGPRA. For example, we would go into historical societies and people used baskets as garbage pails and lamp shades. People had limited knowledge of what great Native art was. If you look at what has happened in the last 30 years, in terms of publications and exhibitions, so much has come out in the last few decades; there has been a total turn around in what people know about Native art. I think for the good.

2. Were works commissioned for all three of the Changing Hands exhibitions?

When you say commissioned, I assume you mean a budget was given to an artist. In each exhibition, I chose the artist first. In many cases, I would go to the artists, in many cases the artists would choose to create something new for the exhibition. It wasn’t a commission because the museum didn’t have the funds to underwrite a specific piece. One of the big contrasts I see between this Museum of Arts and Design (being an American museum) and Canadian museums, the museum doesn’t have the funding to commission works. This has become more difficult today than in the last decade. The difference here is that museums here have a lot of private funding. Works that have been in our exhibitions have often been purchased by private collectors and wind up in museum collections or in private collections.

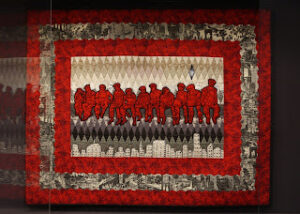

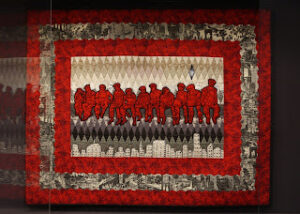

Carla Hemlock

b. 1961 Kahnawake Mohawk Territory, Quebec; lives in Kahnawake Mohawk Territory, Quebec

Tribute to the MohawkIronworkers, 2008

Cotton cloth, glass beads, sequins, cotton/nylon threads

Courtesy of the National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC

Cat. No. 26/7164

3. Could you give a brief description about Changing Hands: Art Without Reservation 3?

The third exhibition is the most about contemporary art. The first two exhibitions have greater reference to tradition; in particular, the Southwest had a strong emphasis on tradition. The second exhibition has strong references to tradition with some breaking points. The third and this was the biggest challenge, there are so many jumping off points for contemporary art (performance, video or mixed media). It really is more about contemporary art with some reference to tradition. I think that the table has turned, there is definitely the reference to cultural roots of these artists that are indigenous.

As an aside, I have a very strong interest in contemporary art. I invited many friends who are interested in contemporary art, and have no knowledge of Native art, and they all loved the exhibition. They picked works that resonated with them, really reflecting their interest in contemporary art. This showed that we are reaching a broader audience. I’m trying to have people forget these preconceived notions of what they think Native art should be.

4. How did your history of working at Sotheby’s and creating a specialized department for Native American art influence this exhibition if at all?

I could not have done any these exhibitions without the background that I have at Sotheby’s. To really understand the exhibitions that I’ve done, you really need to have a broad base of knowledge of historic Native art. The opportunities at Sotheby’s, I’ve seen more collections than most people. I didn’t work in a museum but I appraised many museum collections. Many museum collections have thousands of pieces. I had to handle and identify the pieces. I travelled all over the world looking at collections, I had to know all areas of Native art. I had to know Southwest, Northwest, Northeast, Alaska, Hawaii. I had to know all Tribal Arts including African and Oceanic art as well.

That background of working at Sotheby’s for 25 years, allowed me some basis to then look at the contemporary work and understand what it was based on. Looking at contemporary beadwork I can understand where it’s coming from. Whether people think that’s valid or not is their decision.

My feet are in two different places. One foot is in historic Native art, which I love. I never looked at it as anthropology, but always presented the work at Sotheby’s as art, not as specimens.

My other foot is really placed in the world of contemporary art of which Native art is part. I go to all the Chelsea and Soho galleries, and the galleries in Brooklyn and the Lower East Side. My background gives me the background to make a judgment. I also have an extensive library. Some of my colleagues have focused on one area and can write about one specific area, but what I can do is look at the field in a much broader way, and have an opinion based on what came before and what’s now, this is important in making a judgment.

What always drove me crazy was cataloging Plains beadwork. Looking at amazing pieces of beadwork, I would think, what was this woman doing, what was she trying to do with the patterns? You knew there was some personalization, but you never knew what it was. You had to at Sotheby’s make everything generic.

Now when you have artists who are creating specific patterns to identify who they are, it’s interesting.

When you think about beadwork or other works, they were all made for a purpose. When I think about the North West Coast, the great masks and bowls, all cultures make things for a purpose. The way these things were embellished were so beautiful, I wish they could speak. The artists themselves can’t speak but the works still exist. They are still speaking, just not telling us what we want to know. This gains my respect and admiration. When I see a great piece of Native art, historic or contemporary, I still get weak at the knees.

5. How do you think the art market (collectors, museums, connoisseurs) influences Native arts production?

It varies a lot from region to region. The Southwest is the most obvious. There are certain artists who gear their works towards the market, there artists are working towards commissions, then there are artists breaking the mold.

In the plains area, there are artists who are always challenging themselves, beadwork artists. They always find an audience. In the North West Coast, there are traditional artists, but there are a lot of galleries who support them.

With the Changing Hands 3, I was talking with Barry Ace about finding collectors. It was really hard to find collectors in the USA who collect contemporary Native work, they are not that visible. There is the Berlin Gallery at the Heard Museum, and Legacy Gallery in Santa Fe, but there aren’t many galleries who sell this work. I found communication with galleries for this exhibition the most challenging.

I think the artists in Changing Hands 3 are the most independent of the market system. These artists are the most educated, the most sophisticated of all 3 regions. I talk about this in my essay (see the pdf to read it). These artists aren’t solely relying on the market. One of the challenges for Native art in general is to be in the same playing field as all other American artists, why they are not is a big question. This certainly came up in the panel discussion. I don’t have an answer for this, I think its coming but not there yet.

6. This exhibition is the third in the series, what were some of the challenges you faced?

Depending on the category there were different challenges. Inuit art in general was a big learning curve for me because the artists were un-reachable. My goals were to work directly with the living artists, to show new work (or made within the last 5 years) and ultimately to have a conversation with the artist. With the Inuit art, in most cases, I didn’t have a chance to speak with the artists. The galleries or co-ops were stumbling blocks to get in touch with the artists. In the end, we were able to get the artist’s works that we wanted. Finding works were difficult because there were no formal records, co-ops don’t keep these records. There was no documentation, so it was challenging.

With the other exhibitions, it was challenging finding the work, but it wasn’t as hard as for the third show. For the first exhibitions there was no internet, the artists didn’t all have telephones. Changing Hands 2 was easier. The other challenge for me was re-defining the show.

7. What inspired you to use the title ”Changing Hands: Art Without Reservation 3″?

Richard Glazer-Danay

b. 1942, Coney Island, New York; lives in Corona, California

Crazy Horse War Bonnet, 2009

Hard hat, mixed media

Courtesy of the artist

Image credit: Ed Watkins

The origin of the title refers to the passing on of traditional techniques, materials and stories from one generation to the next, from family to family, from Native hands to non-Native hands, as they would in an Indian market or fair.

Art Without Reservation referred to the content that would be in the exhibition. With Changing Hands 3, I was thinking, we are not really showing traditional art, most of these artists were formally trained versus the first Changing Hands, artists were self-taught. After weeks of soul searching, talking with the director of the museum, when I really thought about it, Changing Hands refers to the artists themselves who are sharing knowledge with other artists and students.

So many of the artists are teachers who have gone back and re-learned material, traditions and stories, that they were not taught when they were young. For the third exhibition, the Changing Hands element is there but it was re-defined. In a way it was a revelation but I think the title still fits, so we left it. The first exhibition of Changing Hands opened in May 2002.

8. Did your vision for the exhibition Changing Hands alter as it developed?

Yes it did. I think more with Changing Hands 3, I thought it was important to include film and video, it is important for contemporary art today. I also thought it was important to include different media and mixed- media installations. I think what was included was most important for Changing Hands 3. I’m kind of a purist, and the mission of the museum of arts and design is about process, artists interacting with their materials. There were certain pieces I felt were important for this exhibition. So there were certain rules that I bent a little bit for each show, when I thought it was important to include specific work.

9. How has this exhibition been received?

Everyone that has seen it has liked it. There haven’t been any reviews. I’m a guest curator, so I’m not at the museum on a regular basis. I’m hoping that it is well received. I think people are afraid sometimes to review Native art. I don’t know why but I think they are. Maybe it is politics. The show is open until October and then it goes to Rochester, then travels to other venues including the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg. It travels through 2014.

10. Will there be a part 4 for Changing Hands?

Well, I would like there to be a branch project, I think it’s important that what I’ve started continues. I’m not sure how to do that. When people talk to me they are excited. Ultimately, I think the work is great. When I look around at the contemporary art scene, the artists I look at in terms of indigenous artists, I think their works need to be seen on a broader scene. I’d like to see a re-visit of the regions as a whole, There are so many artists who we looked at in Changing Hands 1 and Changing Hands 2 who have gone on. There are other generations who have gone another step. I’m not sure what I’ll be working on next.

G. Peter Jemison

b. 1945, Silver Creek, New York; lives in Victor, New York

Ganondaman, ca. 2010

Found paper bag, collage,

acrylic ink

Courtesy of the artist

Crow in the Shadow, 2011

Handmade paper bag, acrylic paint, collage

Courtesy of the artist

Shadows on the Porch, 2009

Found paper bag, China marker, acrylic paint, colored pencil

Courtesy of the artist

Image Credit: Ed Watkins

11. Is there anything else you would like to add?

I hope that people will come and see Changing Hands: Art Without Reservation 3 and get the word out. I think what we’ve done is very different. There have been a number of exhibitions that have happened in the last few months. Changing Hands series has sparked quite a lot. The exhibition No Reservations, I had a laugh at, and I think the approach we’ve taken is very different from it. We don’t show any historic work, we don’t refer to the artists except where they were born and currently live, we include an artist statement with each work, we approach this as a show about contemporary art. I think that is different with what shows have done in the past. Good or bad, I want people to look at this work and have an open mind about it.

Artist Tom Jones and Curator Ellen Taubman

Ellen Taubman is the guest curator for the exhibition Changing Hands: Art Without Reservation 3: Contemporary Native North American Art from the Northeast and Southeast, at the Museum of Arts and Design, New York City, on view until October 21, 2012. She has over 35 years of experience working in the field of Native arts, with expertise in art markets and curatorial projects. Changing Hands is a three-part project that spans one decade from 2002-2012.

Listen to Interview with Ellen Taubman, “Changing Hands: Art Without Reservation 3: Contemporary Native North American Art from the Northeast and Southeast” Podcast here:

If you would like to buy a copy of the catalog, please go to the museum’s website to inquire.

Catalog and images provided courtesy of Ellen Taubman and the Museum of Arts and Design.

Ellen Taubman is an independent curator and art consultant. Taubman is currently engaged in a project with the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Arizona, and was previously a Guest Curator at the Museum of Arts and Design in New York City, where she organized a series of exhibitions focused on contemporary Native American art. Previously, she served as Vice President, Department Head & Expert-in-Charge of American Indian, African and Oceanic Art at Sotheby’s in New York. Taubman is a Board member at Creative Time, a National Advisory Committee member for the University of Michigan Museum of Art, an Exhibitions Committee member for the American Federation of Arts, and a member of Friends of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. She is also a National Advisory member at the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art and a founding Board member of the National Museum of the American Indian at the Smithsonian Institution. Taubman holds a Bachelor of Arts in art history from the City College of the City University of New York. She resides in Manhattan with her husband Bill Taubman and has two children.

Ellen Taubman is an independent curator and art consultant. Taubman is currently engaged in a project with the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Arizona, and was previously a Guest Curator at the Museum of Arts and Design in New York City, where she organized a series of exhibitions focused on contemporary Native American art. Previously, she served as Vice President, Department Head & Expert-in-Charge of American Indian, African and Oceanic Art at Sotheby’s in New York. Taubman is a Board member at Creative Time, a National Advisory Committee member for the University of Michigan Museum of Art, an Exhibitions Committee member for the American Federation of Arts, and a member of Friends of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. She is also a National Advisory member at the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art and a founding Board member of the National Museum of the American Indian at the Smithsonian Institution. Taubman holds a Bachelor of Arts in art history from the City College of the City University of New York. She resides in Manhattan with her husband Bill Taubman and has two children.

Gloria Bell

Gloria Bell’s research and teaching examines visual culture focusing on Indigenous arts of the Americas, primarily from the nineteenth century through to contemporary manifestations. Currently, her research focuses on exhibition histories of First Nations, Métis and Inuit arts in the early twentieth century in Italy, Global Indigenous studies, decolonizing and anti-colonial methodologies, materiality studies, global histories of body art, and the importance of art as living history.

Ellen Taubman is an independent curator and art consultant. Taubman is currently engaged in a project with the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Arizona, and was previously a Guest Curator at the Museum of Arts and Design in New York City, where she organized a series of exhibitions focused on contemporary Native American art. Previously, she served as Vice President, Department Head & Expert-in-Charge of American Indian, African and Oceanic Art at Sotheby’s in New York. Taubman is a Board member at Creative Time, a National Advisory Committee member for the University of Michigan Museum of Art, an Exhibitions Committee member for the American Federation of Arts, and a member of Friends of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. She is also a National Advisory member at the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art and a founding Board member of the National Museum of the American Indian at the Smithsonian Institution. Taubman holds a Bachelor of Arts in art history from the City College of the City University of New York. She resides in Manhattan with her husband Bill Taubman and has two children.

Ellen Taubman is an independent curator and art consultant. Taubman is currently engaged in a project with the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Arizona, and was previously a Guest Curator at the Museum of Arts and Design in New York City, where she organized a series of exhibitions focused on contemporary Native American art. Previously, she served as Vice President, Department Head & Expert-in-Charge of American Indian, African and Oceanic Art at Sotheby’s in New York. Taubman is a Board member at Creative Time, a National Advisory Committee member for the University of Michigan Museum of Art, an Exhibitions Committee member for the American Federation of Arts, and a member of Friends of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. She is also a National Advisory member at the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art and a founding Board member of the National Museum of the American Indian at the Smithsonian Institution. Taubman holds a Bachelor of Arts in art history from the City College of the City University of New York. She resides in Manhattan with her husband Bill Taubman and has two children. Gloria Bell’s research and teaching examines visual culture focusing on Indigenous arts of the Americas, primarily from the nineteenth century through to contemporary manifestations. Currently, her research focuses on exhibition histories of First Nations, Métis and Inuit arts in the early twentieth century in Italy, Global Indigenous studies, decolonizing and anti-colonial methodologies, materiality studies, global histories of body art, and the importance of art as living history.

Gloria Bell’s research and teaching examines visual culture focusing on Indigenous arts of the Americas, primarily from the nineteenth century through to contemporary manifestations. Currently, her research focuses on exhibition histories of First Nations, Métis and Inuit arts in the early twentieth century in Italy, Global Indigenous studies, decolonizing and anti-colonial methodologies, materiality studies, global histories of body art, and the importance of art as living history.