Norval Morrisseau: Artist as Shaman

By Barry Ace

Perhaps more than any other Aboriginal artist in Canada, there is a voluminous collection of published and unpublished manuscripts and writings on the art of Norval Morrisseau. Yet today, we are no closer to arriving at an understanding of

this larger-than-life Ojibway painter who remains shrouded under a veil of mystery and speculation. While many have sought to uncover the romanticized “Ishi-like” primitive who draws from his Ojibway heritage and secretive Midéwiwin spiritual teachings, few have dared to venture into a critique of this complex man. Perhaps, even more poignantly, Morrisseau and those around him, were actively engaged in the mythic construction and public re/presentation of Morrisseau as a contemporary primitive.

A construct that has not only served as a mask to shelter undesirable influences of modernity, but also as a strategic marketing ploy that was incredibly successful in stimulating a lucrative art buying public, by offering them a rare opportunity to own a fragmentary glimpse of a mythical past. As the art buying public, dealers, and art institutions engaged in what can only be described as a Morrisseau “feeding frenzy”, the complexity involved in re-inventing, controlling and sheltering Morrisseau’s public and private spaces from the outside world became a hugely convoluted and contradictory task for all involved, including Morrisseau himself. The personal impact of this monstrosity of an illusion was so enormous, that few were immune from its negative impacts, and perhaps most tragically of all, was the toll it took on the physical and emotional state of Norval Morrisseau.

For many years following his arrival on the Canadian art scene, Morrisseau and those closest to him were mostly successful in shielding the constructed image of Norval Morrisseau from any outside critical scrutiny, but they were less successful in controlling and influencing internal cynicism and scrutiny from within his Ojibway cultural milieu and community. It is from this unique cultural vantage point that we can only now begin to meticulously unravel and dissect the very premise and raisonne d’etre behind the construction of this mythical Ojibway Medusa called Norval Morrisseau, where we find the primitive artist-as-shaman mysteriously shrouded in a romanticized stasis existing simultaneously as a public dream and a private myth.

Having had the extraordinary opportunity, early on in my career, to work for the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development (DIAND) in the Indian Art Centre as Chief Curator, I had the honour to meet, interview and spend time with numerous prominent Aboriginal artists from across Canada, including Norval Morrisseau. As well, I have had the unbridled privilege to work with what can only be described as the most significant collection of contemporary Canadian Aboriginal art in the world. It was during this period, in the summer of 1995, that I had my first opportunity to meet the legendary Norval Morrisseau. Norval was in Ottawa, with his close friend and business manager Gabor Vadas, to attend an exhibition and honouring ceremony bestowed upon him by the Assembly of First Nations. I clearly remember receiving a call from a downtown hotel where Norval asked me if it would be alright if he came and visited the Indian Art Centre. I told him that of course he could come over, and he concluded our conversation by asking me to meet him downstairs with “one of those yellow slips of paper (taxi chit), since he did not have a lot of money to spend on taxi rides.

I agreed to meet him in front of the DIAND headquarters at 10 Wellington Street in Hull, Quebec. Gabor was the first to emerge from the taxi, and I said to him how pleased I was that Norval had decided to come over to see his works in the collection. Gabor was a bit standoffish at first, and I wrote this off as simply a socially awkward situation. In the back seat of the taxi sat Norval Morrisseau looking a lot older than I had expected him to be, but still, he appeared as stately and astute as ever. Both Gabor and I helped Norval out of the taxi to an upright position. Although he seemed to in some pain brought on by severe stiffness in his legs, his staunch independence and gargantuan charisma had not suffered in the least. Norval immediately told me that he had just had an operation to replace both kneecaps, and that his doctor had told him to remain confined to his wheelchair. He went on to explain that after only a couple of months, he went to see an elder on the Squamish reserve near Vancouver, who told him to “throw away that wheelchair”.

Norval said he complied and the old man then gave him a “grizzly bear walking stick”. He went on to recount that his old man revealed to him that “this walking stick is medicine”. I was simultaneously astonished and taken aback, because, Norval, without any prompting from me, immediately launched into a diatribe on sacred healing practices. I have always found this notion of other Aboriginal people feeling the need to validate their “Indianness”, especially to another Aboriginal somewhat difficult to deal with. I quickly came to the conclusion that this was the Norval that I had read about and seen on film, at least the real public Norval Morrisseau. I remember thinking to myself how important performance and self-validation has become in contemporary Aboriginal communities, and I understood that this was largely based on the desire for authenticity.

Norval’s walking stick only further embellished the mystique of his public “Indian” persona, and I remember this particular walking stick was really phenomenal. The top of the stick had a realistically carved full-figured grizzly bear, and affixed directly below, was a real grizzly bear paw, complete with fur, pads and claws clutching a huge white translucent ten inch octagonal crystal. Surrounding the bottom half of the walking stick, were row upon row of triangular rattles, honed from the hooves of deer that clacked and swayed in unison to Morrisseau’s labored gate. To further compliment his

shamanistic persona, Norval wore an incredibly intense red and black northwest coast jacket with a huge graphic Haida thunderbird motif that covered the entire garment. His shoulder length hair was slightly unkempt, jutting out from his head at all angles forming a haloed tangle of black and grey strands. Looped around his neck, he donned a small grouping of medicinal roots resembling miniature two-legged torsos side-by- side, each sewn together with sinew. In his right hand, he clutched a beautifully incised birch-bark container suspended on a thick strip of tanned hide.

Norval proceeded to tell me that this was his “medicine pouch” that contained an assortment of traditional medicines and remedies that he always carried with him. As we entered the main foyer of the building, Norval was unequivocally aware of his surroundings as men and women in power suits rushed past on their way to meetings throughout the Les Terrasses de la Chaudiere complex. Commanding absolute attention, Norval pounded his grizzly bear walking stick on the granite floor of the main foyer and the sound of the rattles emanated throughout the stone interior. His eclectic and eccentric appearance immediately stopped passers by dead in their tracks. He stared back at them for a moment without uttering a

single word, and he turned to me and said softly, “There, I have their attention now. Let’s go and have some tea.” I felt like I had just taken part in some kind of strange theatrical ritual of the past. Something so compelling that I was immediately drawn into it and positioned not only as witness, but as an active participant in Norval’s public performance piece. It was truly an amusing intervention and interruption. Morrisseau had wittingly demonstrated to me the power and effectiveness of his public persona, a time and space where theatre becomes art.

After our tea, I spent most of the early afternoon with Norval and Gabor, pouring over DIAND’s vast collection of Morrisseau works and ephemera, while Norval intermittently interjected personal observations and reflections on various aspects related to the works and manuscripts strewn on the table in front of us. When I began opening the archival grey boxes of materials, I observed Norval slowly surveying the neatly wrapped papers, manuscripts and drawings. I could not help but begin to wonder what was going on in Norval’s mind, confronted with a good proportion of his personal handwritten letters and manuscripts sent to Selwyn Dewdney of the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto in the early 196os.

As more of the material was unveiled, I immediately began to sense tension emanating from Gabor, and he nervously turned to me, and in a very controlled and forthright manner, asked me what the Department was doing with so much of Norval’s personal belongings. For a moment, I was taken aback, but I went on to explain to both Gabor and Norval that the Department had purchased the collection from the Nancy Poole auction of Selwyn Dewdney’s estate in 1985. The Department purchased the material for $35,000, in an attempt to thwart the sale of the collection to a New York City art dealer interested in acquiring the collection. As well, the foresight of then Indian Art Centre manager Tom Hill had ensured that this national treasure remained intact and in Canada. Gabor swiftly turned to Norval and said, “Why did you give so much of your personal stuff to Selwyn?” “Did he take it from you?” “I think we should take all of this back.” Norval sat motionless for a moment, and he slowly shifted his head to look directly at Gabor and said, “Selwyn was my friend, that’s why I gave it to him. He was my friend.”

Norval went on to say that he had often wondered what had ever happened to this material, and he said that he was glad to find out that the Department had acquired the collection, and that it was in safe-keeping. These letters are the only handwritten documentation of its kind that remains from the long-standing relationship between artist Norval Morrisseau and Selwyn Dewdney, a Research Associate in the Department of New World Archaeology at the Royal Ontario Museum. The letters span the years 1961 to 1977 and provide an unprecedented précis account of Morrisseau’s prolific career and personal observations and guidance of several key players who helped Morrisseau along as he broke onto the Canadian art scene in the 196os.

During this visit with Norval in 1995, he answered many questions I had about the manuscripts and artwork contained in the collection, and I remember at one point, we came upon a small painting on two fragments of birch-bark, stitched together with spruce root. It immediately reminded me of several old Ojibway Midéwiwin scrolls I had seen at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto. I asked Norval about this particular piece, and he told me that it was in fact a remnant of a birch-bark scroll that originally belonged to his grandfather. Norval went on to say that his grandfather Moses (Potan) was a Midé elder. “This was my grandfather’s [pointing to the incised figures and lines scratched into the surface], and I painted this [pointing to the symbols and imagery painted in acrylic overtop of the incised markings] on top.” I was curious to know what medium he was using when he was painting on bark and roofing back paper. He told me he would often paint with oil, acrylic, or tempera, and sometimes when supplies were low, he would use any combination available. I was impressed with his ability to recall time, place, and events, so I asked him if he remembered painting on this particular work on birch-bark.

He looked at me and said, “A lot of people ask me if I remember doing a particular painting, and I tell them of course I remember doing that painting, and I remember exactly what I was thinking about at the time when I was doing it” (Morrisseau, personal conversation, August 30, 1995). Before leaving the Indian Art Centre, Norval took from his birch-bark box a small vial containing an amber-like fluid, and he removed the wax seal and drank the substance. He turned to me and handed me the empty vial and said, “Now, you put this in that box too.” I remember thinking, at the time, how clearly Norval understood his now legendary role, and how any extraneous ephemera he was wearing, handling, or carrying was somehow connected to the validation of his shaman persona, and like the Dewdney time-capsule, all must be preserved, documented, and protected for the sake of posterity. I also began to understand how important it was to Norval to maintain his public persona as artist and shaman and how difficult it was for him to distinguish after so many years, what was real and what was not.

After Norval and Gabor left, I began leafing through an old copy of Tawow magazine published in 1974. I came across a film review by Tom Hill of the National Film Board of Canada’s The Paradox of Norval Morrisseau. Hill noted that the film was “an intelligent and sensitive viewpoint developed on an artist so complex that any attempt at an analysis of his art and personality would ultimately only skim the surface (Tawow 1974, p.4)”. Still, I thought, after almost twenty-two years, Hill’s statement couldn’t have been any closer to the truth. And it was on this late summer afternoon in 1995 that I too, realized that I had only begun to scratch the surface of this legendary and paradoxical figure.

Yet in contrast to all of his complexities and contradictions, his distinctive and prolific paintings, his beautifully articulated legends and stories, and his legendary public performance, I felt that the some of the truth behind the construction of Norval Morrisseau must lie somewhere deep within the Morrisseau-Dewdney letters. And if I were ever going to come close to understanding this truth, I would have to take the letters in their entirety and begin to fill in the blanks. As I began to read and reflect on the correspondence, I soon began to realize just how profound, intense, and determined Morrisseau’s letters were. I also came to the undeniable conclusion that Morrisseau not only knew who he wanted to be, but also how he was going to get there. Yet, in spite of his relentless and complex negotiation strategies, there was one oversight that Morrisseau failed to take into consideration, the personal toll this arduous journey would have on him. A painful and tragic toll that would not only leave him physically and emotionally scarred and debilitated, but also continually plague him throughout the course of his entire career.

For me, having access to these letters that remain relatively obscure and inaccessible, has provided me with a rare opportunity to trace the origin of Morrisseau’s public persona and to see who else played a critical role in aiding this construction. From the outset, Morrisseau was already utilizing strategies to position himself as a “carrier and holder of traditional knowledge” and he used his privileged position to garner the trust of Dewdney and other potential advocates. What else becomes quickly evident is Morrisseau’s ability to shift his persona from one of naivety and innocence, to mysticism and esotericism, to profundity and genius and to do whatever else may be advantageous to a particular situation. Yet through it all, one can also see clear examples where narcissism and manipulation were pivotal to ensuring that he could play individuals off against themselves to advance his cause, and later, where he uses these strategies to deliberately reject, sabotage, and undermine, these very relationships he worked so hard to garner. This is also well born out in agent Jack Pollock’s autobiography, Letters to Dear M. Pollock unequivocally states that Morrisseau was a master manipulator who often rejected the advice of Pollock and even went so far as to turn on Pollock, dragging him into a lengthy and ridiculous court case. Yet, in spite of all the outrageous antics and performances that transpired between Pollock and Morrisseau, Jack still admired Morrisseau and continued to support, promote, and contribute to Morrisseau’s success as noted in the 1979 publication Art of Norval Morrisseau.

In his autobiography, Pollock paints a very flattering picture of Morrisseau by stating that “one hesitates to use the word genius and, indeed, the qualities necessary for such a term are rare; however, the contribution to the Canadian cultural scene made by, his incredible ability with the formal problems of art (colour – design – space) and his commitment to the world of his people, gives one the sense of power and image that only genius provides (Pollock 1974, p.5.)”.

The letters begin in 1960 when Selwyn Dewdney was in the Nipigon/Thunder Bay region of north-western Ontario conducting research into rock art sites. During one of his visits, Dewdney began hearing about a young Ojibway artist who would soon become an important informant to him on the locality and meaning behind sacred rock art sites. Surprisingly, it was Selwyn Dewdney who first met Morrisseau, presaging Pollock’s first encounter by 2 years. Over the next 15 years, Dewdney would continue a close relationship with Morrisseau, and continue his research on the Ojibway petroglyphs, pictographs, and birch bark scrolls, published in Indian Rock Paintings of the Great Lakes (1962) (co-edited with Kenneth E. Kidd, Curator of Ethnology, ROM) and The Sacred Scrolls of the Southern Ojibway (1975).

Although Dewdney’s initial interest in Morrisseau was strictly motivated by his personal work on rock art sites, Selwyn quickly began to take an avid interest (as an artist himself) in the artistic and literary aspirations of informant Norval Morrisseau. Dewdney actively bought Norval’s work and introduced his work to friends and southern art dealers and to his colleagues at the Royal Ontario Museum. Dewdney further assisted Morrisseau by agreeing to help him with the editing and publishing of Morrisseau’s seminal literary work Legends of My People, The Great Ojibway (1965).

The first reference to Norval Morrisseau appears in a letter from the summer of 1960, sent to Dewdney from Constable Bob Sheppard, who at the time, was working with the Ontario Provincial Police on Mackenzie Island. Sheppard’s letter introduces Norval as a young, energetic, and aspiring artist from the community of Beardsmore. From the outset, it appears that Sheppard was also quite taken with Morrisseau’s cultural tenacity and distinctiveness of his artwork. Sheppard obviously had close familiarity with Morrisseau, and from his letter, one immediately gets the impression that he really wants to help Morrisseau by recommending him to Dewdney:

“Enclosed are some crayon drawings of a young Indian I have met from around Beardmore way. His crayon drawings are good and his watercolors are even better. I have some of his watercolors inside birch baskets and they are really beautiful. His name is Norval Morrisseau, and he has had grade school and has done plenty of reading since leaving school, and he himself studies and collects Indian lore as well as being by way of an artist. He has plenty of access to his material being an Indian himself.

He is looking for work, married, and no children, and it seems a shame he doesn’t get a chance to sell his work or find many interested people. It is not the sort of thing to sell to tourists as it would go unnoticed except for the novelty. Too bad the Museum couldn’t use a series of Indian paintings, or could they? What do you think this boy’s chances are ?? He can draw and paint, grew up with the people and knows the stories by heart. It seems a shame that his talents can’t be made useful and available (DIAND, ADAS 306065 June 7, 1960, BS)”.

The letter from Bob Sheppard must have certainly sparked Selwyn’s interest, especially when Bob stated that Norval “studies and collects Indian lore” and has “plenty of access to his material being an Indian himself”. Dewdney was always on the lookout for informants to assist him in his work on rock art sites. One month later, Selwyn was in Beardsmore interviewing Norval. The day after their first encounter, Selwyn appeared to be genuinely delighted with the young artist’s potential, as he recounted in a letter home to his wife Irene in London, Ontario:

“Sunday morning we took a L&F kicker over to Mackenzie Island, and spent most of the day with Bob: taking notes on his description of Indian dance routines, eating lunch, interviewing the amazing Norval Morriseau … It was a really weird experience the day before, meeting an Indian who (a) was filled with a deep pride of race, origin, and identity (b) was almost a stereotype of everything you expect to find in an artist: sensitivity, a sureness about what he wanted to paint, didn’t want to paint, liked and rejected, a craving for recognition, complete disinterest in money and material rewards. He is 28, married (to a woman he met in the San at Fort William, who is now pregnant), tall, unmistakably Indian in features. Maybe I’m a bit rosy-eyed about him; but there was a quiet dignity and gentleness with strength that tempt me to use the word nobility.” (DIAND, ADAS 306065, July 13, 1960, SD).

From Selwyn’s initial account of Norval, it is clear that Morrisseau had already arrived at the decision to become a famous artist and he seemed to have all the charismatic and artistic attributes to make it happen. Furthermore, Norval could never have made such a strong impression on Selwyn had he not already possessed a deep understanding of his Ojibway culture, for clearly Dewdney was quite adept at singling out imposters. In the same letter, Selwyn recounted to his wife that he had “spent a rather fruitless afternoon with Bob interviewing two Indians, but missing the man reputed to be (I now doubt it) a Medayweninny (DIAND, ADAS 306065, July 13, 1960, SD)”. Selwyn must have perceived something extraordinary about Norval to speak so highly of someone of whom he had just met.

It was on this first visit that Selwyn also met Dr. Weinstein, a medical officer stationed in Cochenour, who was an avid patron and promoter of the young Morrisseau. In the same letter to his wife, Selwyn remarked that he was also intrigued by Dr. Weinstein, whom at the time was a highly educated, cultured and worldly man. Selwyn was also impressed by Weinstein’s own talent as an aspiring artist and equally impressed with Weinstein’s personal collection of “primitive” art from around the world and library of art books:

“In the morning we broke camp, picked up our laundry, and drove over to Cochinour to view more paintings of Norval that had been bought by a Dr. Weinstein. I wanted to meet the latter, who had become a sort of patron of Norval’s. A Montreal Jew, who lived outside of the Jewish community there, he studied medicine – and painting in Paris. There he met his wife, a sixth generation Sabra from Israel … What to do about Norval filled most of the hour and a half I had with Weinstein.

Weinstein, who has exhibited in Paris (whether in a well-known salon or on a street corner I don’t know), paints very competent and individual abstracts – slightly reminiscent of Herb Ariss’ work – and has an impressive collection of objets d’art from all over the world, is even more impressed by Norval than I am. But what to do? Weinstein hopes to get him a surface job at Cochinour Mine (he can’t work underground on account of his T.B. bout), so he can paint in his spare time, and support his family. We agree that it would be fatal to get him down to Toronto for a few months of lionization and exposure to all sorts of pressures. Norval wants an exhibition. Bob Sheppard imagined they would hire him as an assistant at the Museum, and led him to hope this. I promised to use him next summer if he learns to handle a kicker and drive a car – but anything else would be impossible. He has a grade 4 education. That’s our Norval.” (DIAND, ADAS 306065, July 13, 1960, SD).

It is from this initial description of Weinstein and his “impressive collection of “objets d’art” that questions arise as to the amount of influence Weinstein and his collection had on the young Morrisseau. Although no interviews have ever been conducted with Dr. Weinstein regarding his impact on Norval’s stylistic development, an early biography prepared by Selwyn in late 1961 or early 1962, recounts his initial conversation Weinstein and his impressions of the influence of Weinstein’s art collection and library on the young artist. Included in this biography are some thoughts on the source and motivation for Norval’s creativity:

“The Cochenour medical officer, Dr. Weinstein, who had had training as an artist in Paris, and spent his holidays with his Paris-born wife travelling widely and collecting primitive art, took a keen interest in Norval, buying his paintings, and encouraging him to use his native lore as subject matter. I spent half a day with Weinstein discussing Norval’s art; and we agreed that it would do him nothing but harm to go east for formal training. Though he had access to, and was fascinated by, Weinstein’s library of art repros, Norval seems to reflect few influences; one of the most amazing things about him being the way he invents an Ojibway way of visualizing things, without the existence of any pictorial tradition to which he has had any access. He has a real passion for his people’s past, and a sense of mission in passing it on in pictoral form. He depends largely on dreams for his ideas; and in this is firmly rooted in the dream-centred religion of his people.” (DIAND, ADAS 306065, 1961-62,SD) .

Although the biography clearly stated that Norval was “fascinated” with Weinstein’s impressive collection, it appears from the biography that Norval incorporated very few elements and had clearly formulated, rather than emulated, his distinctive style of painting that would later become regarded as the Woodland School of painting.

In an article by Dewdney in Canadian Art in January 1963, Selwyn further notes that:

“At the goldmine in Cochenour where he (Morrisseau) was then working he had struck up a friendship with the mine doctor, himself an amateur artist of some ability, Joseph Weinstein. Weinstein and his Paris-born wife were world travellers, with a collection of primitive art, and an ample art library. When I visited them the next day I leafed through the volumes of reproductions that Norval had seen. With few exceptions, the doctor and his wife told me, contemporary and classical western painting had appealed little to him. Navajo and West Coast art, on the other hand, had made a strong impact, although without any visible influence on his painting. The last traces of any doubt that might have lingered vanished when they brought out their own collection of Morrisseau’s paintings on birch-bark. These owed nothing to any other art form. This was an artist who relied solely on his inner vision.” (Dewdney, Norval Morrisseau, Canadian Art, p. 33-34. 1963).

Only twice in the thirteen years of correspondence did Norval ask Dewdney to send him information on other Indian cultures. In fact, the first request occurred in the fall of 1960 in a letter to Selwyn where he asked, “can you send me some Indian designs or pictures, the ones that could be put on art.” (DIAND, ADAS 306065, November 7, 1960, NM). On first glance, it is quite easy to simply read Norval’s request for new ideas to copy. But Norval was already painting on birchbark, and he had already developed his unique Woodland signature of painting, so his request was most likely for ideas and motifs that he could adapt as an addition to his work. It is also important to note that Norval was not illiterate, nor was he so isolated and “primitive” that he did not have access to library books. Norval attended Residential School in Fort William (Thunder Bay) and at the age of 15, he left school. Bob Sheppard also noted in his letter to Selwyn that Norval “has done plenty of reading since leaving school, and he himself studies and collects Indian lore.” (DIAND, ADAS 306065 June 7, 1960, BS). In a subsequent letter written to Dewdney in 1962, Norval clarified his intentions in a similar request made for books in lieu of payment for art work he had sent to Toronto art dealer Bob Hughes:

“Sent Bob Hughes 18 blk and Reddish drawings, if he has a hard time selling them at ten dollars each tell him to lower them to $6.50 or $7.00 each. With the money ask him to get me some books about Fish of North American, Animals of North Americ, Birds of the world or N. American Books on Indians of North America. Different titles – of beliefs- lore- B.C. Sulpturing – totem poles art- Indian art etc. I have a private collections of books. So far I have about 7 books. I never pickup no ideas from these but I appreciate book of this type and I like to read at times.” (DIAND, ADAS 306065, January 12, 1962, NM).

What is also revealed later on in this same letter is that Morrisseau had already been exposed to European art movements, more specifically, the 20th-century movement of cubism. At one point in the letter, Norval makes direct reference to the artistic merit of his most recent works and humours Selwyn by making a direct reference to Picasso, which may have originated from either his discussions with Weinstein or from his familiarity with Weinstein’s library. Norval states, “I am giving you some of my work. If you don’t like none put them into the stove to make heat like Picasso does, ha ha, aldo these are not of the best please excuse but I will give you some good ones next time I promise you my friend (DIAND, ADAS 306065, January 12, 1962, NM)”. It appears that Norval was not that impressed with the work of Picasso, for he did not attempt any forays into cubism.

It is probably an undeniable truth, that Morrisseau was unequivocally “awakened” by a number of sources of influences (a moot point for any artist), yet all sources clearly credit Norval as the founder of a new and unique style of Woodland painting. Morrisseau’s distinct style of painting would become a staple and source of inspiration for many of his contemporaries, including Carl Ray, Daphne Odjig, Roy Thomas, Blake Debassige, and Richard Bedwash. Even today, many Aboriginal artists continue to follow in his footsteps, fusing their own unique stylistic preferences and innovations.

Today, the Woodland school of legend painting continues to be shrouded by a veil of romanticism that has its origins in the mystique of Morrisseau. From the letters, we begin to see how this veil of secrecy developed, and much of this lies with Dewdney’s coaching and preparation of the “coming out” of Norval Morrisseau to the academic and artistic elite of the Toronto scene. In what I describe as nothing more than a construction and marketing strategy to sell the public on the authentic Indian myth, Dewdney was highly influential in moulding Morrisseau’s persona in these early years. The very fact that Morrisseau complied, reveals perhaps a little bit of naivety, but even more so, his eagerness to accommodate and garner the trust and respect of Dewdney. Morrisseau recognized a gift horse when he saw one.

It is interesting to note that in the letters, Morrisseau’s strategic ability to conform to Dewdney’s challenges and investigation rose to a high level of intellectual discourse that certainly impressed Dewdney. And although Norval was unequivocally the “knower of knowledge”, he strived really hard not to offend Dewdney, and he used different strategies to prove to Dewdney that he was an authentic “Indian” informant.

In Morrisseau’s first letter to Dewdney in the fall of 1960, Norval confidently declares his depth and understanding when compelled to speak about his personal quest for the preservation and archival storage of his cultural knowledge. Early on, Norval recognized the mutual benefits and future possibilities this chance encounter would provide, and he was more than eager to offer his assistance to Selwyn no matter what the cost. I truly believe that Morrisseau inwardly compared himself to Oglala Sioux elder/shaman Black Elk, and that his relationship with Selwyn was one similar to the one between Joseph Epes Brown and Black Elk, albeit with the eventual publication of Morrisseau’s collection of Ojibway legends and beliefs. It is interesting to note that in a letter dated January 12, 1962 requesting books, Norval clearly notes his familiarity with Black Elk by telling Dewdney that he had a personal copy of The Sacred Pipe – Black Elk’s Account of the Seven Rites of the Oglala Sioux, recorded and edited by Joseph Epes Brown, in his personal library.

For those who are not familiar with Black Elk, he was a spiritual elder who carried with him oral teachings of the sacred rites of the Oglala Sioux. In his old age and close to death, he lamented that he was the last surviving, of three apprentices of Elk Head (Hehaka Pa), Keeper of the Sacred Pipe, to pass on this sacred knowledge. Elk Head had warned Black Elk that the teachings must be handed down for “their people will live for as long as the rites are known and the pipe is used. But as soon as the sacred pipe is forgotten, the people will be without a centre and they will perish (Black Elk 1971, p. xvii)”. Black Elk chose academic Joseph Epes Brown to record the sacred teachings to ensure that the teachings would be preserved for the time when his people would seek cultural renewal. Did Norval share a deep affinity to Black Elk? Did he see this burgeoning relationship with Selwyn as a likeness to Epes Brown?

“I often remember the visit we all had last summer and I remember what you told me that we will see one another again. I trust this will be soon. As I look forward to that time … I wish to ask you I am sure you know a lot of people and I have written a book on Ojibwa beliefs of all nature … If you have time again to come into the Lake Nipigon area next summer I would take you to some places that you might have not been at the time of your trip into the area. There is a place at Lake Superior where the Ojibwa used to put offerings in a sacred cave to a demi-god and I believe a lot of this stuff could be recovered for the museum. Also if you wish to see where the Ojibwa used to get a blue and white coloured liquid that oozed out of the rocks and that was used for medicine I could arrange for you to see. This place as well as a place the Ojibwa used to place their dead on trees, and other stone medicines also a place where the Ojibwa of Lake Nipigon used to get Copper for their pails etc. this has to be very secret as copper is considered sacred among the Ojibwa – and to other rock painting you have not seen about 3 in all. I will have a holiday next summer. Perhaps then we could arrange this.” (DIAND, ADAS 306065 November 7, 1960, NM).

One month later, Norval writes again:

“Sorry I did not enclose a letter with the writings if you think that there is a chance to publish these I send you I would be very glad to get some royalty’s or money from them not that I want the money that bad. As I would be foolish to think that way but my idea is I wish to use this money to a good purpose. I wish only one thing to be an artist and to be respected as one – and my paintings …. I think I could get some information on rock paintings. Its secret to the Ojibwa but being an Indian and respected as one I will be told just by the asking also what I wish to get is a tape recorder if my beliefs are accepted with a tape recorder I could get alot accomplished and I could get some Indian chant’s and Medawiin and Wabino-wiin songs as well as many other I know alot of Indians who would be glad to sing on a tape recorder also some legends are very long on a tape recorder every thing that take’s place in the legend is recorded. Selwyn I ask you as one artist to another. Not for my-self but for my people. Try to help me out. To put in a good word for me time and again to the right party. I will promise you as a freind I will do my very best to repay you in a way someday I will help you get alot of information about the Ojibwa – what you would wish to know more – about conjuring or rock paintings etc. I will do my best to get some information also there is alot of ancient Indian stone medicine compounds in form of liquid that oozes out of the rocks, colors of light blue and white to use as medicine for pains and other sickness. I will get this medicine this summer. Have it and other matters analyzed.” (DIAND, ADAS 306065, December 10, 1960. NM).

Whether or not Morrisseau truly felt an affinity to a Fenimore Cooper “Last of the Mohicans” fantasy, he clearly set out to affirm his positioning as someone worthy of documentation. Dewdney on the other hand, quickly established his own dependency on Morrisseau, and from the outset, appeared to be quite taken by Morrisseau’s seductive and irresistible charm. Dewdney was so enamoured with Morrisseau that he went so far as to advocate for the inclusion of Morrisseau’s work in the collection of the Royal Ontario Museum, and convinced his colleague Kenneth Kidd, Curator of Ethnology to acquire more information and commission additional works from Morrisseau. Selwyn quickly fired off a letter back to Norval asking him to send two samples of his work; one on birch bark and one on plywood. Morrisseau completely and unequivocally complied. It is interesting at this point to note whether or not Dewdney was beginning to feel that Norval might be playing him a little. For Dewdney went into great detail regarding the request to ensure Morrisseau clearly understood the seriousness and implications. He also suggested that Norval include an unedited (which he underlined in the letter), verbatim account of each legend associated with the works, and told Norval that he would use these works as a leverage to convince a Toronto publisher to consider Norval’s collection of beliefs and legends.

It is at this point in the correspondence that Selwyn begins to allude to a growing concern for Morrisseau’s public presentation, authenticity and reception, particularly by the academic and professional museum communities. Dewdney seems to assume a very paternal role and begins to coach Norval on a variety of aspects concerning his art practice, types of materials and professionalism of the finished product. One quickly gets the impression that Dewdney may have had some concerns that Morrisseau might be perceived and revealed as an impostor. Dewdney would have been certainly aware of this potential and the damage it could inflict on his professional reputation and life’s work. This must have been further compounded by Morrisseau’s unpredictable and uncontrollable behavior during his bouts with alcohol.

“Kenneth Kidd, Curator of Ethnology (in charge of the section of the Museum that deals with North American races and their cultures) and his two assistants, Walter Kenyon and Ed Rogers, both of whom have had considerable contact with the Ojibway Indians, all saw the colour photographs of your paintings that I took last summer; and they were impressed. Mr. Kidd would like two samples of your paintings for the Museum’s collection. I would suggest that you send him one on birch bark (perhaps, since you have to wait till spring for more bark, Dr. Weinstein might contribute one of his), and one on plywood. You might also send him a decorated bark dish like the one you made for Dr. Weinstein, if obtainable …. Could you also write an account of the legend connected with each picture; and get someone to type it for you, without changing your wording.

Next, get some tracing paper from the mining engineer’s office and trace the outline only (not the details, unless they have a special meaning) of all the figures or objects in each painting. Write a note, explaining all you know about each figure or object and its connection with it, number the note, and number the figure or object it explains, on the tracing.

This is a lot of work. But I am sure the Museum will be glad to pay you for your time and trouble. Once these samples of your work are in Toronto I can go down there to see that a reliable book publisher sees them. I will look after this personally, and find out from him what the possibilities are of getting a book published in book form. This will be quite easy as I have connections with most of the Toronto publishers … Meantime, keep working on your painting, trying out all the ways you can think of to improve your technique so as to get results that satisfy you most. Painting thinly in oil colours on the raw wood might give you some of the effects you want; and scraping the bark, or staining some of the areas might help too. If you use oil paints thin them with turpentine rather than oil, so you get a dull, rather than a shiny finish. You might also try getting rock textures with oil colours as a background for your designs. An artist owes it to himself to experiment with many effects in order to reach the highest possible quality. And, for you particularly, who wants the world to respect your people, their beliefs and legends, it would be of value to learn all you can about the many techniques of painting, so as to earn the respect of your fellow artists in the white world … Please use my first name, from now on – as one artist to another.” (DIAND, ADAS 306065, November 15, 1960, SD).

Selwyn’s overly controlling concern over Norval’s ethnographic contributions and artistic forays is clearly revealed in the letter of March 6, 1961. In the letter, Selwyn goes into great detail offering a plethora of advice on technique and medium. By this point in their relationship, I believe it was becoming exceedingly difficult for Dewdney to allow Morrisseau to enter the art world without his guidance and protection. It is at this point that Dewdney clearly makes an attempt to direct Morrisseau’s public persona. Dewdney crosses the fine line between researcher and artist/informant by suggesting that Morrisseau try painting on moose-hide using colors that are similar to those used by “prehistoric Indians”. This is a pivotal letter in unravelling the Morrisseau myth, and as one begins to read between the lines, we begin to see that there is more here than meets the eye. Was Dewdney knowingly attempting to market Morrisseau’s image to an art buying and academic community, or was he just overly concerned as a friend to help Morrisseau prepare for the public scrutiny of the south. It is also important to interject at this point that Morrisseau was not a complacent player in this relationship, and both were actively engaged in creating some kind of public persona. One must remember that Morrisseau was an avid collector of “Indian lore” and a collector of books about various Aboriginal cultures of North America. It would have been very clear to Norval exactly what Dewdney was proposing to him, and Norval did not want to negatively impact or terminate what he must have felt was a mutually profitable relationship. Dewdney offers Morrisseau the following advice:”In a separate parcel I am sending you several tubes of oil paint, two oil brushes, and two pieces of moose-hide tanned by a local leather company.

The oil colours I have chosen because they are all “earth colours” that is, they occur naturally. All but the terre vert (earth green) are similar to the pigments used by the prehisitoric Indians. I added the terre vert because I thought you might want to use at least one cool colour. Any of these oil colours thinned out with turpentine will apply to hide, will never change colour, and will not flake off.

The oil brushes are in two sizes. With a little practice you can get any kind of detail you wish. For instance, if you use the corner of the small brush you’ll find you can show even the fisher’s claws in the morning in the painting I have copied from one of your drawings. But these brushes must be cleaned thoroughly after each use. Rinse them out in turpentine, wipe them dry, then work soap or detergent into the bristles till it lathers. Rinse with water, soap again, and again, until the brush is clean. Treated like this the brushes will last for ten years or more … On your painting of Misshipeshoo, for instance, you used too much shellac in one area, so that it is noticeably thicker. In time this would be distinctly yellower than the rest. In the thunderbird painting only the medicine balls are varnished. The tempera colour elsewhere in the painting is unprotected and would flake or run under damp conditions. Also shellac or varnish over tempera gives a “cheap” appearance that is unworthy of the quality of thought and feeling that go into your paintings.

Another point, that will seem very unimportant to you, is that whoever crated your paintings for shipping, put nails through the middle of two of the paintings. Perhaps I should put it this way. Your work is to show to non-Indians the richness and variety of Ojibway beliefs and legends through your paintings. Those paintings should be “dressed” as carefully as a great Meedayweninny would have dressed himself in the old days before going to a Meeday ceremony. To put it in other words you are not only an artist, but a representative of your people. To gain respect among the non-Indians your paintings must show more than the thought and feeling, forms and colours that make them works of art. They must also show craftsmanship, a concern for the way the painting is prepared for display or sale – the finish of the surface. This will help to explain to you why I am going so slowly in encouraging you. Before we make a serious attempt to sell or exhibit your work we must be sure that you have found a way of rendering it that will (a) satisfy you as an artist (b) satisfy the non-Indian viewer.” (DIAND, ADAS 306065, March 9, 1961, SD).

Selwyn’s use of cultural metaphors and his concern over presentation is clear in his comparison to a Midewiwin elder preparing for a ceremony. His choice of words, although somewhat paternal, does reveal a heartfelt respect for Morrisseau. But it is also couched in Eurocentric concerns to shelter Norval from potentially damaging and disparaging criticism by the predominantly non-Indian world.

Norval quickly bought into Selwyn’s advice and began to produce a massive body of work based on Dewdney’s advice, straying very little from what Dewdney had told him to produce. Norval even went so far as to begin sending Dewdney his work for critique. The letter of April 20, 1961 is perhaps the best example of the level of discourse that transpired between Norval and Selwyn on issues relating to construction and representation of Ojibway mythology.

It is clearly a well-documented lesson by Selwyn on the importance of presenting oneself as the pure and authentic primitive. The debate arose out of Selwyn’s concern over the accuracy of one of Norval’s visual depictions of Neebanape and Maymaygwaysiwuk, two Anishnabe water beings of Lake Nipigon. Selwyn took issue on two points. First, he queried Norval on the inclusion of breasts on a mythical figure Neebanape, citing that no drawing in his recollection revealed Neebanape with breasts. Secondly, he challenged Norval on the concept of female demi-gods in Ojibway myth and legend. Again, this interchange appears to be an early test case of Dewdney’s to ensure that Norval is not only a reliable and authentic informant but one who is willing to accept scrutiny when confronted by a challenging and critically astute intellectual audience.

“One thing I suggest you be very sure of: that “white” man’s concepts do not in any way creep into your paintings. For example, I have seen a number of 19th-century Indian drawings of Neebanape, and none shows female breasts. Even if this is an Indian idea, it is so much like the European idea of a mermaid that buyers will wonder how Indian it really is.

Or what about the idea of a “Mrs.” Maymaygwess? Have any of the older Indians you have spoken to over the years ever mentioned a female Maymaygwess? Perhaps I am mistaken but all that I have read or heard so far suggests that the demi-gods were either male or sexless.

Norval, you know how interested I am in your mission – to pass on the ancient legends and beliefs of the Ojibway people to the “white” people of Canada. When my ancestors came over to North America from Europe they brought the legends and beliefs they had borrowed from many other races.

For instance, when the Romans invaded England, the Britons (like the Indians of North America after Columbus), were pushed back into the bush country and treated as third-class citizens by the newcomers. Gradually, as they lost their faith in themselves, Roman ideas crept into their own beliefs, and the ancient Druid religion of the Britons slowly faded. Yet even today 2,000 years later, mistletoe – a sacred plant to the British Druids appears in our Christmas decorations.

This is where your importance comes in. The more you can express in your writing and painting the strongest and oldest Indian beliefs, the more likely it is that they will be picked up by the non-Indians and become a part of our Canadian heritage. But if, in your honest attempt to build a bridge between your people and other Canadians, you – say your mermaid painting with the breasts says – “Look, our beliefs are just like yours” you will only convince the non-Indian that the Ojibway people have little that is new, or strong, or different, to offer the rest of the world.” (DIAND, ADAS 306065, April 20, 1961, SD).

Norval responds:

I agree with you about Neebanape about the breast I did not like the idea myself at all but I put it there to see what you might think of it but I knew right along what you might say but I did not mention now about Neebanape. I know that the Indian long ago would not paint the breast because it would not look good to the painter at the time to put a breast on the figure .. I know Neebanape the Mermaid as the Europeans called it is a woman the Ojibwa knew this water dweller to be a women of the lake Nipigon area – also why I painted the Demigod or water God besides the mermaid was for one reason that both live in the water but they got no relationship or contact of any kind whatsoever. If she could be referred as a Demi-god or Demi-goddess or a water goddess I would not say at this time- but according to some beliefs of my people she is known to be powerful in her own way. I could be wrong and if I am wrong then the rest of my tribe are wrong …. you tell me also that the Demigods are all male and sexless if they are how can a male Demi god have children or small offspring – take the case of Missipisso the water god at a certain lake where this demigod lived for years, the Ojibwa never travel upon this lake in fear of this being but offered some offerings to it such as – tobacco dogs etc.

One day about some hundred years ago a woman lost her baby while portaging the lakes in this area. Knowing she lost her child, she called upon her father who knew the mighty thunderbirds for help. All that night and next day the very sky itself was dark and showers of lightning poured into this lake. Two days later everything was calm. The lakes were like this (Norval draws three unconnected lakes in a row), and when they looked upon these lakes, there was none except one long lake like this (Norval draws one large, long lake). On the surface, the old man, the father, saw two things floating around dead. When he came upon them, there were the two water god cubs. Now, if the being was male and sexless, how could he have these cubs or small cat-like things? So there must be a female – now about Mrs. Maymaygwessii. I agree with you that this being was never seen by the Ojibwa except the male; she did not have any importance. But the male did. I will refer to you again about offspring.

I was told by a few of the older people I have talked to that there was a female Maymaygwissi. I have heard at times where offspring are mentioned that they looked cute and that their children are hairy. These I was told are the children of these most respected water dwellers. Here again, I do not know if I could call them demi-god, except there is the one demi-god I knew that is (Norval draws a cat-like animal); that is him – he is more powerful of the water beings – in water the snake for the land and thunderbird for the sky. And if there is no Mrs. Maymaygwess, then where do the children fit in this picture – so there must be some female demi-god, but they are not as important as the male – but the mermaid sure found her way to respect. She is known to change herself into a baby who is lost by the lake crying; then if there are kids playing nearby that hear its cry, she would take them away. I was told this when I was small that she would take me away, so I sure kept my distance from water.” (DIAND, ADAS 306065, April 25, 1961, NM).

Selwyn clearly articulates his growing concern that Morrisseau publicly present himself as the authentic, pure, and primitive Ojibway Indian in his statement that Norval must ensure that no “white” concepts creep into his work. Dewdney sends a very clear message to Morrisseau that he must never incorporate any elements of modernity or cross-cultural influences in his work. And it is at this point that Morrisseau understands that if he is going to be successful in the “white world”, he must play the part. It is also ironic that both Morrisseau and Dewdney are well aware that Morrisseau’s grandmother was a devout Roman Catholic, and this influence unequivocally rubbed off on Morrisseau. It would be several years later, while incarcerated, before Norval would dare to present this part of his persona to an art-buying public. But early on, Norval was still eager to demonstrate his support and compliance to Dewdney by offering his services to actively engage in the preservation and cultural authenticity of Midéwiwin songs and teachings on a tape recorder:

I could get some Indian chants and Medawiin and Wabino-wiin songs as well as many others. I know a lot of Indians who would be glad to sing on a tape recorder. Also, some legends are very long. On a tape recorder, everything that takes place in the legend is recorded. Selwyn, I ask you as one artist to another. Not for myself but for my people (DIAND, ADAS 306065, December 10, 1960, NM). It would not be until well after Legends of My People, The Great Ojibway (1965) and much public success and acceptance would Morrisseau free himself from external control and begin to include unauthentic themes in his work. In the early 1960s, Morrisseau was still testing his abilities, strongly influenced by the power of both Dewdney and gallery owner Jack Pollock. As his career begins to flourish after his sell-out exhibition at the Pollock Gallery, Morrisseau is well aware that the potential of his dream of becoming a famous artist and revered Ojibway shaman is on the verge of materializing. Still cognizant of his dependence on Dewdney, Morrisseau strategically downplays any material gain from his professional endeavors and reaffirms to Dewdney that fame will never detract him from his idealistic pursuit.

“Today I received the amount of two hundred dollars, a loan from the Dept of Indian Affairs. I will start doing paintings this week, on good quality paper from Prushen [?] art supplies and moosehide with oils and art paper with oils and others with watercolors… I am so glad, my friend, not for the money involved but to put forward in art form the ancestral beliefs etc., for the deceased and living Ojibwa Indians of the Great Lakes. I thank you again… you have helped me out a lot. Through you, Selwyn, my cherished dream is coming true, at least it is at the doorstep with one foot in. Anyway, I won’t get lost but take this luck in a respected way a little by little. I will take it in, and I will come out developed like an artist. I will never change in my way of thinking; my way will always be for my people, the great Ojibwa.” (DIAND, ADAS 306065, February 16, 1962, NM).

Again in the spring of 1962, Norval writes:

“You must wonder at times how come I know so many things, well, being an Indian, I was told whatever I want[sic] to know. I study things ever since I remember. And let us say the demi-gods look upon me with favoring eyes and that the spirits of my ancestors are driving me or that I lived before in the past and took up in human form again. Ojibwa belief states that the Indian lives again once he dies again he will live. Reincarnated[sic] is this what you call it, do you believe in (curse)… I am very glad I have found a friend who is interested in my same interest. One day I might be famous, but I won’t ever forget I owe it all to my people. Some who are afraid to do this art, etc. But I hope this will help in a way – to bring out what they know – no use to brag to themselves what a great nation they were or what great culture they had to themselves they have to show it to their white brothers. Then they could all be happy…” (DIAND, ADAS 306065, [Spring], 1962, NM).

By 1962, Norval is very careful and cognizant of how to present himself, and he has clearly mastered his own use of esoteric cultural metaphors. But this newly constructed traditional and authentic Morrisseau was not entirely cohesive, and there was one very large gap in the persona suit. For years, Morrisseau had been battling perhaps the most feared demi-god of all, alcohol addiction, and he regularly succumbed to fierce drinking bouts that followed intense periods of creativity. Both Dewdney and Pollock were well aware of Morrisseau’s addiction, and both became increasingly concerned over the impact on Morrisseau’s health and creative production. Dewdney and Pollock desperately tried to shield Morrisseau from the press, for it is obvious that they felt his bouts of irrationality and denial would destroy what both had tried so hard to develop and promote. Both Dewdney and Pollock’s overly paternal concern and desire to shelter Morrisseau are noted in Pollock’s handwritten response to Dewdney, who appears to be conspiring with Pollock as to how they are going to protect Morrisseau from speaking out while under the influence to the media.

“Excuse the familiarity, but I already feel ourselves to be on a first-name basis though our common interest in Norval. Herewith a tentative biography, revised from the one I went over with Norval at Beardmore, but essentially accurate. Yes, I think you are wise to keep Norval under your roof. I am sure that if it is put up to him that he is representing his people he will control his drinking, but a smart reporter might get him loaded if he got him alone in a hotel setting.” (DIAND, ADAS 306065, August 30, 1962, JP).

Dewdney documents another bout with alcohol that is not only disturbing but reveals Morrisseau’s own personal turmoil and struggle to live up to imposed expectations concerning his impending publication of his manuscript. Dewdney appears to be quite concerned and almost afraid of what he is encountering when Morrisseau arrives at his home in London, Ontario. The note reveals the uncertainty and unpredictability of the situation, as Dewdney scribbles his immediate thoughts and observations (at times illegible) on a piece of brown paper torn from what appears to be a brown paper bag. Morrisseau discloses to Dewdney that he wants to destroy his manuscript, citing that he didn’t believe or mean certain passages he had written. More specifically, it was a reference to a passage where Morrisseau appears to encourage Indians to abandon the past and embrace Catholicism. It is also revealing that Dewdney notes that “we later found (the passage) and took it out.” Was the passage removed to accommodate Morrisseau’s concern or Dewdney’s concern? The note fails to clarify this. The note is also interesting in that it reveals Morrisseau’s state of mind during this period. He appears to fear the potential onslaught of criticism and scrutiny that may arise, and his confusion about how he will be able to handle difficult and probing situations is apparent.

After a couple of years of acceptance by Dewdney and Pollock, Morrisseau appears to be in personal conflict that perhaps he may be exposed or labeled as an impostor. I really do not believe that Morrisseau was struggling with any concerns of community retaliation for speaking about what many have called taboo subjects. For if there is any truth to this claim, perhaps it is partially rooted in the federal government’s legislation in the 1920s to 1940s, whereby individuals were convicted for practicing traditional ceremonies, such as the Sun Dance and Potlatch. It is clear that during this time, the Midéwiwin also went underground, and ceremonies were practiced at night to avoid discovery and possible retaliation. Morrisseau would have been well aware of this shift in cultural practice from his grandfather, so it is probable that any concerns raised by his community were not related to what Norval was depicting or documenting but simply concerns for safety from federal intervention and prosecution. In a letter from the spring of 1962, Norval alludes to his concerns that there are “some who are afraid to do this art. But I hope this will help them in a way – to bring out what they know.” (DIAND, ADAS 306065, No date [Spring], 1962) Morrisseau’s concerns were for the preservation of traditional knowledge that had been driven underground as a result of federal intrusion, and it is unlikely that they were related to the myth surrounding taboo.

“Arr. 2 a.m. well loaded and slightly unsteady but speech under full control. He had decided to go to Toronto and see his lawyer. “I don’t want anybody to stand in front of me or behind me with any lawyer.” No account of events downtown, but he had spent the earlier part of the evening here reading through his manuscript. Now he wanted to destroy it – burn it all. He had said things he didn’t believe, didn’t mean. He was referring to passages which we later found and took out, in which he was urging his fellow Indians to adopt Christ and forget the past. The old ways brought no peace of mind; the new ones did, etc. Now he was asking why he talked that way. Maybe it was just because he wasn’t mature when he wrote it (2 years ago).

There followed an unforgettable scene in which he prayed to R- M(?) aloud in Ojibwa, translating phrase by phrase to me as he went. It had the flavor of an extempore evangelical effort, with occasional phrases reminiscent of the General Confession. But the Ojibway poured forth in precise articulation and crisp cadence, beautiful to hear – reminding me of Canon Sanderson at his best-very unlike Norval’s usual low rather indistinct English or the slurred loose-lipped Ojibway when he talked with his grandfather. This, with the bookish-sounding “O great Manitou, you know everything about me. You have told me that if I make one slip I will be nothing. Great Manitou, I am nothing. (reducing voice to a mere whisper) nothing. You know that.” Apparently all day he had been going over the last night’s dream – interview with R.M. (At supper time I had had the impression as the meal started that he was praying – he had his head down and his lips might have been moving slightly). Also, we had been editing his MS, which begins with concepts of death, heaven, and the afterlife, in which Ojibway and Christian ideas were intermingled.

During the talk, all sorts of misgivings – about the Pollock Gallery – “I can never go back there” – about white men generally – tumbled out. Yet when he left, he took his latest paintings with him and spoke of dropping in at Jack’s to leave them there. I got a cup of coffee into him, and he was beginning to drop his cigarette ashes in the ashtray by the time the taxi arrived. Also, he referred to his interfering with my sleep as something he regretted. “Suppose I went to Toronto and got a thousand dollars of my money and spent it all, and then came back here and wanted to borrow $200. What would you think of me?” “I’d worry about your wife and children.”

At another point, he said that he had always known he would become a notable person. There was one voice that he could rely on, that told him the truth; but there were other voices perhaps – the demi-gods – and if he listened to them he became confused.” (DIAND, ADAS 306065, September 1962 SD).

Less than one month after this encounter, Dewdney decides to write a grant proposal on behalf of Norval. Dewdney knowingly positions Morrisseau into a convenient “primitive” package in what appears to be a lame attempt at garnering a sympathetic ear of federal bureaucrats to take pity on this simple and confused Indian artist.

“Caught in the treacherous cross-currents of two conflicting cultures he will sometimes swim magnificently and sometimes helplessly drift. Heretofore it has been in the quiet backwaters that his art afforded that he has found the strength for each fresh encounter. I believe that a similar urge motivates this new venture; one, I might add, that has been on his mind these past two years. And I am sure that whatever new material he collects will further stimulate his painting.” (DIAND, ADAS 306065, February 28, 1963, SD).

Despite these periods of confusion, fear, manipulation, seduction, and addiction, the letters at times reveal a very astute and profoundly prophetic Morrisseau. It is here we discover a different Norval Morrisseau, a self-reflecting individual talking about the high and low points of his career, and confronting his ongoing struggle with alcohol. The letter offers us the only glimpse into the private Morrisseau that we get in the letters. Yet, despite its honesty and frankness, it is hauntingly foreboding of things to come.

“So many wonderful things happen. Sold 11 paintings to Glenbow, furnished my house – bought art supplies – clothing blankets food etc., put some money in the bank, also moved to a place that is real good. Paid four months’ rent in advance – so rent is no worry this winter, food is plentiful, we have bought a television which is very good for all of us here at the Copperbird’s dwelling, bought a chesterfield suite and a record phonograph with radio – and plenty of art supplies …. I don’t drink much. Although I feel like it at times

but try not to give in to my wantings. I realize each day a little by little that it is not good for me. If I feel like drinking first I think how I will feel on a hangover and this helps for I really feel very bad. It destroys my body soul and mind – so it is no use to drink, Right …. I agreed to take Pollock back on the basis that he is not to be an exclusive agent and all works of art shipped to him to pass through the three trusties and whatever action he takes to be approved by the trusties all art to be recorded in number file – if necessary in photo file, all monies made by sales to be put in a trust fund whereby I could get $150.00 per month for a start whether I sell or not and the trusties to look after my money and that the trusties cannot be full authority of the handling of such money – but again to ask for my consent before action although they hold that power to handle it and if the trusties felt that Pollock is not doing his best to promote such works of art – that there should be openings for others to sell such – so I hope you agree with my arrangements … all I need now is to educate myself. I am going to buy all kinds of books and records for all music that will be helpful to me – to further my knowledge .. Yes, my friend, you would indeed be surprised to visit me now as our house is furnished all my antiques of brass copper artifacts medicine bags etc are all displayed and have good cabinets and buffets to place or stuff art that is all framed is on the walls etc. I am proud now in a sense that is not too proud in my body or mind but proud that at last I feel famous artist as I am glad people come to my home to see me instead of the old tumbled-down old place we lived last summer when you were here. Oh yes about the book. How are you getting along with it is there a possible chance it may be published this year, Let me know how you are getting along with the book as a lot of people are asking about it.” (DIAND, ADAS 306065, January 6, 1964, NM).

By 1964, Norval has arrived at the pinnacle of his newfound success and the inevitable realization of his dream; the publication of his legends and beliefs. Selwyn writes Norval telling him that “One of your dreams is about to come true. I am going to Toronto tomorrow to negotiate the final contract for your book; and I am already well into the job of editing it.” (DIAND, ADAS 306065, May 18, 1964, SD)”. Two days later, Dewdney writes,

“The contract between us and the Ryerson Press (no relation to Millie!) is enclosed herewith, ready for your signature and that of a witness, who can be anyone not in your immediate family … It’s a good contract; especially the part (section 18) that gives you a free hand with the drawings – an arrangement that many publishers would be reluctant to make.” (DIAND, ADAS 306065, May 22, 1964, SD).

After 1965, with the international success and public acclaim of Morrisseau’s work and his increased involvement with agent Jack Pollock, his correspondence with Dewdney drifts off substantially. Also at this point, Dewdney no longer types his letters on carbon paper, and no longer staples the return response with his carbon copy original. Although Morrisseau periodically corresponds, Morrisseau no longer needs the support of Dewdney, and he now turns his attention to the art-buying public and Jack Pollock. After numerous bouts of drinking, marital break-ups, extended periods of incarceration, a National Film Board production, a large public commission for the Indian Pavilion at Expo ’67, Morrisseau continues to make artistic advancements in his work. He moves away from the predominant earth tones in his paintings and he shifts his subject matter to include elements of modernity, colonization, Christianity, environmental impacts as well as more complex undertakings in his legend paintings.

His palette transforms into brilliant hues of reds, blues, greens, yellows, and purples that we considered taboo earlier on, and his canvas size increases to large mural paintings. Perhaps some of his best works stem from this period of production, if not certainly, his most well-known. Indian Jesus Christ, Lilly of the Mohawks, Jesus, Joseph, and John the Baptist are a fragment of work while incarcerated in the 1970s. As Morrisseau’s career escalated, so did his aloofness and his transient lifestyle. It was becoming next to impossible for Selwyn to keep track of Morrisseau’s revolving addresses. Many individuals were constantly searching for Morrisseau for interviews, exhibitions, commissions, speaking engagements and to pay him royalties on his reproduced prints and images in publications. Many letters and documents from this later period pertain to these kinds of inquiries sent to Dewdney. One such example is a request for information on Norval’s whereabouts from Frank Flemington, Manager, Royalty Department, McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited, dated Toronto 1970.

“It is frustrating, the attempt, to track down the elusive Morrisseau. All I can suggest is that you forward his mail c/o his agent, Jack Pollock, Pollock Galleries, on Dundas St., opposite the Provincial gallery. Since Jack is selling out (to begin again on a reduced scale, he tells me) it might be an idea to telephone him of suggestions as to a future mailing address. Pollock, incidentally, has been Norval’s agent off and on since Morrisseau first emerged and far and above any of the many erstwhile agents, in terms of sales and returns to Norval.” (DIAND, ADAS 306065, January 28, 1970, SD).

Again, one month later Dewdney writes to Mrs. Handley of the Indian and Northern Curriculum Resource Centre, University of Saskatchewan. He states, once again, “you’re only one of many who are seeking the elusive Morrisseau, but you might try the latest address that I picked up in Banff ten days ago, in the hope that he’ll stay put long enough for you to reach him.” (DIAND, ADAS 306065, June 14, 1970, SD)”.

By 1976, the correspondence between the two had all but evaporated, and it appears that Dewdney no longer shared a close connection with Morrisseau. Other artists began to appear on the scene and began to actively pursue Selwyn’s assistance to help them achieve the same level of success Morrisseau had under his tutelage. One such artist was Richard Bedwash, an Ojibway artist from Long Lac, Ontario who religiously followed in the footsteps of Morrisseau, emulating the Woodland School of painting. Richard wrote to Selwyn from the Guelph Correctional Centre in the fall of 1976.

“Just wanted to know that I have come across to see your name on the Canadian Native news in Toronto. Also, I have noticed that you are an instructor as a Native artwork. But I sure would like to learn more about it. I would be very much pleased if you could send me some samples that would give me some ideas. I have a few paintings I have done. But I know for sure I have to learn a lot more also learning how to pick my colors. So I would like to have some Indian patterns and some books if you have on hand. I would have a lot of time to study art here as I am doing time here at Guelph Correctional Centre. Also, I’m an Indian boy from Long-Lac Ontario: hope to hear from you in the near future.” (DIAND, ADAS 306065, September 7th, 1976, RB).

By this time in his life, Selwyn was not interested in taking on another artist. He wrote to Tom Hill at the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development asking Tom if there was anything he could do to help Richard in his artistic pursuits. Selwyn received a positive response from Tom and included it in his letter of regret to Richard. Selwyn’s letter is impressive for it very eloquently and succinctly summarizes his innermost thoughts regarding his heartfelt aspirations for Norval. It provides us, once again, with a last glimpse into the underlying relationship that ensued between Dewdney and Morrisseau. In this final narrative, we are confronted by a man who has not only matured in age, but

(This article is restored from aboriginalcuratorialcollective.org which is not retrievable in entirety)

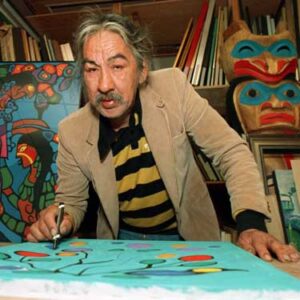

Norval Morrisseau (called Miskwaabik Animiiki in Anishinaabemowin, meaning “Copper Thunderbird”), artist (1931/32 03 14 – 2007 12 04). Morrisseau was a self-taught artist of Ojibwe ancestry. He is best known for originating the Woodland School style in contemporary Indigenous art. His deep spirituality and cultural connections guided his career, which spanned five decades. Morrisseau is considered a trailblazer for contemporary Indigenous artists across Canada.

Barry Ace is a practicing multidisciplinary artist currently living in Ottawa. He is a debendaagzijig (citizen) of M’Chigeeng First Nation, Odawa Mnis (Manitoulin Island), Ontario, Canada. Ace’s work responds to the impact of the digital age and how it exponentially transforms and infuses Anishinaabeg culture (and other global cultures) with new technologies and new ways of communicating. His work attempts to harness and bridge the precipice between historical and contemporary knowledge, art, and power, while maintaining a distinct Anishinaabeg aesthetic connecting generations.

Barry Ace is a practicing multidisciplinary artist currently living in Ottawa. He is a debendaagzijig (citizen) of M’Chigeeng First Nation, Odawa Mnis (Manitoulin Island), Ontario, Canada. Ace’s work responds to the impact of the digital age and how it exponentially transforms and infuses Anishinaabeg culture (and other global cultures) with new technologies and new ways of communicating. His work attempts to harness and bridge the precipice between historical and contemporary knowledge, art, and power, while maintaining a distinct Anishinaabeg aesthetic connecting generations.