Photography Credit to John-Finnegan Lin

The Land Wants You Back

Ottawa International Animation Festival: September 25-27, 2024

Debaser Fall Pique Festival: September 28, 2024

Featured Artists: Djama Clappis, Fox Maxy, Soloman Chiniquay, Jo Daisy-Gowan, Juliana Sech, Rhayne Vermette, Quinne Larsen, Aghalingiak Ohokannoak, Eva Grant

Additional artists: Silas Grenis, Yasmeen Grant, Lesley Marshall, Melanie Golder

Installation team: Calum Jeacle, Nick Schofield, and Tyler Nykilchyk

Debaser team: Rachel Weldon, Katie Manners, Sandra Ngenge Dusabe

Some Background

Kalhwa7alap (hello in St’át’imcets), my name is Eva Grant and I am an Indigenous/Eurasian emerging curator. I am also a filmmaker and media artist whose practice encompasses hybrid narratives, digital art, Land Defence, machine learning, and research-creation. I graduated from Stanford University in 2019 and am an ImagineNATIVE Originals writer/director, a member of the TBA-21 Academy’s UN-facing research group called “Ocean Futurisms,” a Sundance Institute Native Lab alumna, and a former AGO x RBC Art Gallery of Ontario emerging artist-in-residence. I have a strong interest in time-bending audio-visual works that re-examine Indigenous land-based teachings within a digital era. The Land Wants You Back is my first curated exhibit. Using film, digital art, poetry, photography, textiles, projection, analogue technology, and found sculptural elements, this exhibit honours the witnessing and sharing of ancestral knowledge while resisting surveillance culture. Once upon a time I was a Legal Observer – a trained volunteer who supports the legal rights of activists by providing basic legal guidance and serving as an independent witness of police behaviour at protests, demonstrations, and occupations. Our brains are fallible; our eyes can be deceived. Being a Legal Observer often means documenting arrests in case charges need to be contested down the line. I saw a great deal of violence, and became hyper-aware of the ways in which surveillance, security theatre, and what I would call ‘capturing technologies’ (phones, cameras, etc.) shape cultural movements and artistic production. A key aspect of this work is that we do not attend these movements unless our presence is specifically requested by organizers. Since then I have become far more interested in the invitation to witness, rather than the act of witnessing itself. The witnessing was forensic. It meant accepting a role as an independent observer who documents an interaction between people who had also accepted roles: protestor-police-personhood-politic-body. Push… pull. Technological mediation became about capturing, rather than holding. And while it did good in the world, it pushed me to think further. By contrast, the invitation represented a desire to be known that, to me, was sovereign. It represented a form of governance and, moreover kinship. What happens when people, families, groups, or communities, invite witnessing on their terms? I think that makes a village. What happens when each act of witnessing forms an indelible archive, shaping a place over time? I think that becomes the Land.

The Land Wants You Back exists somewhere between a call to return and a reciprocation of desire. It represents an attempt to preserve, with love rather than authority, the personal and collective memoirs of specific spaces, landscapes, and epochs. It embraces entanglement and multiplicity, hypertexts and networks. It acknowledges that many of these memories and moments would not exist without the capturing effects of technology, but it also affirms that some things simply cannot be held. It welcomes the digital as a new immaterial realm, interacting with the material and the ecological to reframe people and places. Reckoning with the influences of colonialism and territoriality, these artists are using technology to make new landscapes. These works of art engender geological shifts that open dialogue, give new meaning, and accompany one another in their formations. It was important to me to create a world where my knowing was not central to the viewer’s experience. I wanted to curate a space where each narrative, context, history, and mystery was something inherently desirous, something that demanded all your care, all your attention. A space where works of art were not simply consumed but experienced, experimented, played with, and layered. To sum up my aspirational curatorial ethos at this moment in time, in this place, I opine that multidisciplinary artist, writer, educator, and curator, Sarah Biscarra Dilley, says it best. Sarah is a member of the yak tityu tityu yak tiłhini Northern Chumash tribe and Director of Indigenous Programs and Relationality at Forge Project. In this collection called, every pattern needs a passage, Sarah writes of a village as “a place of observation or gathering of peoples at important moments or being part of the worlds through solitude, the collapsing of time here is a complementary echo of multiplicity. It is a world-place, woven with the stories of peoples throughout valleys, across mountains, and along tributaries of language, capable of holding each in simultaneous existence, teaching us what colonialism tries to make us forget through territoriality. There are three names for this area, in three languages, each holding significance to another lesson of place and the possibility of learning to sing in continuous rounds, not speaking over one another’s knowing¹.”

The Art

A) The Land Calling You Back (2024) (sculpture, poetry)

Credit to John-Finnegan Lin

“The Land Calling You Back” is an interactive recombination of sculpture, phone-phreaking, and spoken word. It was the heart of the exhibit, the switchboard through which all channels ran. The piece consisted of three rotary phones that could be found nestled on earthy plinths around the arts court. Each rotary phone (models from the 1970s which I purchased at a thrift store) was meticulously shrouded in moss and lichen, suggesting perhaps disuse. Each one was gutted of its original wiring and fitted with a hand-made contraption: SD audio player built with an 8-pin microcontroller. I was inspired by phones in escape rooms which play a pre-recorded message when picked up, and the innovative communication methods utilized by Vietnam Draft Dodgers who settled in British Columbia. Picking up any one of the phones and holding the receiver to one’s ear triggered a recording of a poem by artist and Land Defender Djama Clappis, as though delivered through the phone from Huu-ay-aht Territories in Coastal British Columbia all the way to Anishinaabe Algonquin territories. The poems, each addressed to an intimate interlocutor and thematically linked by explorations and exultations of decolonization, collective liberation and Indigenous sovereignty, are as follows:

- The future has no crowns, no red jackets

- Love after Empire

- On Falasteen, On Quuas Liberation

- I am Reminded

- Kiixin

- Renewal

The piece was a welcome exercise in interactivity and simple ingenuity. I enjoyed the many implications behind “The Land Calling You Back”. The poems themselves seemed to invoke wistful phone calls from erstwhile lovers, ancestral invitations to return to homelands, and missed connections across space and time. It was lovely to bring Djama’s work to Pique. They are a DJ, they’re undeniably cool, they would have fit the vibe perfectly. They are a storyteller who embodies Afro-Indigenous resistance, survivance, and love in everything they do. Djama’s ancestral lineages are of the Somali and Nuu-chah-nulth peoples (Huu-ay-aht First Nations) and they are a frequent collaborator of mine throughout our shared timelines on the unceded homelands of the Songhees and Esquimalt First Nations.

B) MAAT Means Land (2020) (film)

Fox Maxy (Mesa Grande Band of Mission Indians and Payómkawichum) is a director and artist based in San Diego, California, whose films have screened at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF), International Film Festival Rotterdam, and the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures. She makes vibrant, kaleidoscopic films that mutate genres and ripple between narrative and non-fiction storytelling. Maxy is a 2024 Chanel Next Prize winner, and her first feature length film, Gush, premiered at Sundance Film Festival in 2023. She describes her work as being rooted in safety, mental wellness, and endurance. Fox and I were Sundance Institute Native Lab fellows in successive years and I have admired her work for a long time. Her film, Maat Means Land, serves as a graphic self-archive and a devoted historiography of a place. It includes film, phone videos, found footage, and screen recordings of computer games like The Sims. Playing on an endless, shimmering loop on the back wall, Maat was a fulcrum of compositional chaos. To have such a site-specific work prominently displayed definitely served to broaden the boundaries of the exhibition space, as well as to ground the presence of other unceded Indigenous Lands here in this space in a good way. Fox is so good at exploring the question, what does it mean to come from somewhere? In Fox’s world we are treated to karaoke nights, interviews with incarcerated firefighters, beach days, interpretive dance numbers, sidewalk repartee, fierce NDN Aunties, and politically-savvy digital avatars. She invites us to think about her lands, to hold in our minds its many features, environments, surroundings, peoples, elements not untouched by colonialism but showing those scars without shame.

Credit to John-Finnegan Lin

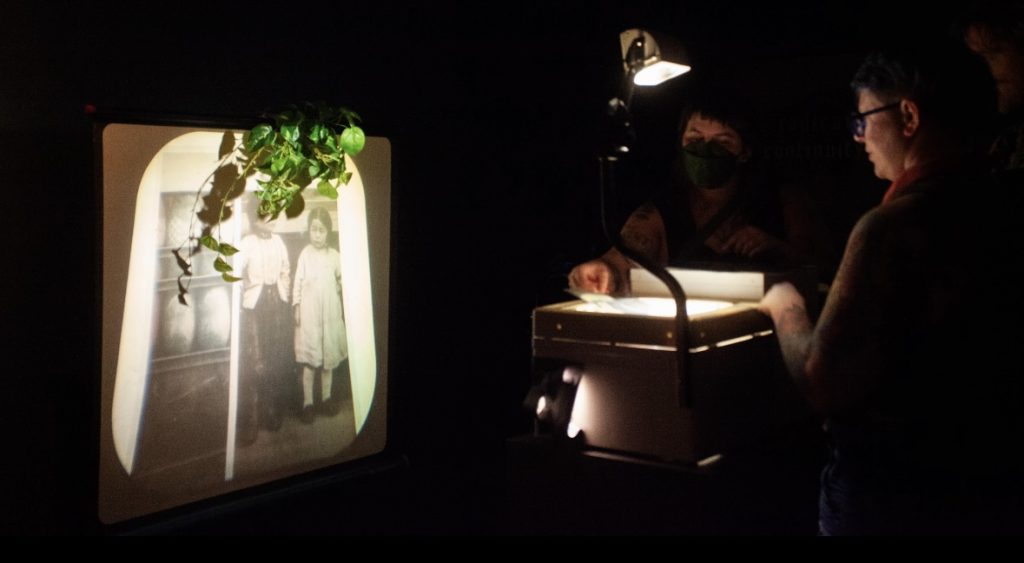

C) Land Acknowledgement (various) (acetate prints)

This installation work required the use of a vintage M3 overhead projector, transparency film, and an inkjet printer. Digital artworks were printed on acetate and displayed in the exhibition space, where visitors were encouraged to layer the sheets over top of one another to create new constellations. I was excited to display digital art in an unconventional way, utilizing lo-fi technology to create copies which could be freely and playfully manipulated without risking an original work. There were nineteen sheets total, representing the work of three different artists.

i) Selected characters created by Quinne Larsen, a Chinook illustrator, writer, and musician based in LA. She makes comics, songs, and short films (one of which is premiering at Sundance Film Festival in January, 2025!), and she has worked in animation for many years, graduating from CalArts and working as a trainee at Pixar. She has worked on shows for the likes of Sony Pictures Animation (The Mitchells vs. The Machines), Frederator (Costume Quest), Cartoon Network (We Bare Bears), Netflix Animation (Centaurworld), and Disney TVA (The Ghost & Molly McGee). A 2023 Sundance Institute Native Lab fellow, Quinne is currently completing an original graphic novel for First Second Publishing. I am drawn to the way Quinne’s work explores artifacts, anachronisms, and the arcane through the logic of dreaming. Quinne’s works evoke a feeling of ritual and mystery, rawness and precision, aided by great instincts when it comes to colour and composition. The pieces selected, concept art of characters, are full of personality and history.

ii) Snow Buntings, and Owl & Raven, by artist and curator Aghalingiak Ohokannoak. They are Innuinait and grew up primarily in Ikaluktutiak (Cambridge Bay), Nunavut. Aghalingiak identifies as a lifelong artist and traveler whose creativity is deeply linked to their relatives. About Snow Buntings, Aghalingiak says: “my Atata(grandpa) always says [they] are a sign that spring is here. Hearing their busy chirping and seeing them flutter by and around my grandparents deck as they get plump on the feed left out for them is a sure sign that even with it still a bit nippy out… it’s spring.” And for the eponymous Owl and Raven: “The two have such a constant relationship in the stories I grew up on. Whether it be a story of frustration, or of being cooperative, I’ve heard them so often and see them often that they’re such a playful inspiration.” Aghalingiak was one of three Inuit artists chosen for the inaugural Nunavut Artist in Residence Program hosted at the Winnipeg Art Gallery, where they explored a “recent focus on and research into Inuit traditional tattoo history and embodied practices.” This interest in tattoo and adornment is reflected in their illustrative work. Characterized by heavy black work, fine lines, and natural textures, these two pieces were popular as top layers.

iii) also featured on acetate was some of my own work, which I plan to build on as an artist/technologist-in-residence at Artengine (fun Arts Court coincidence: I am a New Suns Worldbuilding fellow this year). This series is called No Dominion, after the Dylan Thomas line “and death shall have no dominion.” It is also a rebuke of the colonial classification of my Salish territories as being terra nullius (“land of no one”), and ripe for taking. Crafted from unceded Indigenous territories and digital realms with the help of computational geography tools, No Dominion is a work of post-apocalyptic speculative design. It is inspired by the “ghost villages” left behind in British Columbia after the 1862 Pacific Northwest smallpox epidemic (an apocalyptic plague that wiped out whole families, communities, and lineages) as well as scenes of urban decay in British Columbia. These images depict Longhouses, fishing cuts, pit houses, and other traditional Salish structures digitally reimagined, never lived in layered over and under images of empty parking lots and disused apartment complexes. Making use of the open-ended sensibilities of ethnography and natural history, No Dominion raises questions about ecological transformations and their ties to hegemonic infrastructures of genocide. No Dominion unearths histories that are not lost, simply waiting, in our tide beds, salmon forests, and berry patches, as storied places of local Indigenous nations as well as sites of reciprocity and entanglement between many living beings. Outside of time and historicity, I posit not a utopian elsewhere we need to map out via an ethos of discovery, but a sense of a digital space which Indigenous peoples can fill with our ancestral teachings.

D) Security Blanket (2024) (textile)

Interdisciplinary artist Jo Daisy-Gowan describes Security Blanket as “a manifestation of longing for places that cease to exist due to development and gentrification.” I was drawn to Jo’s work for the nuanced way it addresses complex feelings around surveillance, impermanence, class, and institutional memory. The quilt is composed of imagery taken whilst walking through the artist’s hometown via Google Streetview, set to the year 2011, when certain familiar landmarks still existed. These images were then made physical through silk-screening and quilted with linen to create an object that can hold and protect a person, even when certain spaces no longer can. Security Blanket is a fascinating transformation of surveillance into an open-sourced memory, mirroring the superimposition of satellite images, aerial photography, and GIS data that makes Google Earth what it is. Through quilting Jo is able to soften the stark images of loss, adding them to a long and very human tradition of archiving and preserving home through the wearable and portable medium of textile. Jo Daisy-Gowan is an interdisciplinary visual artist living, creating, and playing on the unceded territories of the Ləkənən peoples, also known as Victoria, BC. Jo is completing their BFA in Visual Arts at the University of Victoria. Primarily working within the realms of painting, photography, writing, and the physical/conceptual spaces where those mediums intersect, Jo’s praxis focuses on interpersonal and community-oriented care, intimacy, grief, and liberation, and is not separable from her experiences as a queer and neurodivergent individual. Jo has exhibited at Sweetpea Gallery, the University of Victoria, The Kawartha Gallery, and The Orillia Museum of Art and History.

E) Selected works from wahiyaba o’zaza tapa and ake huchimachach (various) (photography)

“The Stoney language has no word for goodbye, only, “I will see you again in this life, or the next”.” Soloman Chiniquay is a documentary photographer and filmmaker living between xwməəkwəyəm, Skwxwú7mesh, səlilwəta? territory and their homelands of Treaty 7 territory. Three works each from their the series wahiyaba o’zaza tapa (which were published in a book by the same name in 2022, featuring poems by jaz whitford, Yujin Aspen Kim and DEBBY FRIDAY), and the series ake huchimachach were featured in this exhibit, under a handmade LAND BACK banner that has made its way from film sets to frontlines and back. Soloman has worked on such films as The Body Remembers When the World Broke Open, Joe Buffalo, and Belong. Their photography is a refraction of the very ways in which they themselves are welcomed into witnessing expressions of Indigeneity. They describe their enduring subject matter: “the land and the people on it, the ways people use and connect to the land, and the artifacts they leave on it.” I see Soloman’s work as carefully framing the Land as subject replete with grief and longing and autonomous expression) and the Indigenous eye as mirroring that grief, longing, and autonomy. Soloman’s work, point-and-shoot images that are at once familiar and conceptual, represented a chance to slow down. His black and white images have an important iteration quality to them, a boundless offering to witness raw expression of Indigenous love and labour, and perhaps to become implicated also in the dismantling of the colonial condition.

Credit to John-Finnegan Lin

F) Degrees of Intimacy (2024) (video)

Degrees of Intimacy is a new work of video art by the wonderful artist Juliana Sech, who is based on unneeded Lekwungen Territories. She lives, and works on the unceded lands of the Lekwungen-speaking peoples of the Songhees, Esquimalt and WSÁNEĆ nations. She is an interdisciplinary artist – a species of creative who is adept in many media and therefore for whom the chosen medium is a direct reflection of that work’s central concept. Juliana gravitates towards sculpture, video, photography, performance, and installation. Juliana holds a BFA with Honors in Visual Art from the University of Victoria. She has exhibited, published and screened work for the Ministry of Casual Living, Sweetpea Gallery, Resonance Collective, the University of Victoria’s Audain Gallery, The Layaway, THE SHOW, and This Side of West.. Recently, she showcased a solo exhibition, called “to those found, in mirrored hearts”, with the fifty fifty arts collective. I think of Juliana as a curator’s artist. She has curated & co-curated multidisciplinary art exhibitions including Soft Spit, Liquid Prism, fluid, Killjoys, and served as Sexpo’s Art Director in 2022 & 2023.

Through her work, screens become sculptural objects to be observed at different angles, heights, and distances. Her piece, Degrees of Intimacy is a video art piece measuring the heat transfer of an intimate body interaction between partners and the self through the use of an infrared thermal imaging camera. It maps the invisible exchange between two people whose relationship is built on a foundation of radical reciprocity, and consent, inviting viewers to observe a moment of intimacy and comfort. In 1929, Hungarian physicist Kálmán Tihanyi invented the infrared-sensitive electronic television camera for anti-aircraft defense in Britain. Today, infrared and thermographic technologies are employed in the military, the aviation and surveillance industries, and construction. In the context of this piece, the bright and ever-shifting colours represent the deep ways in which our bodies and our visibility are interlinked.

G) Extraits d’une Famille (2014) (video)

“Please enjoy this film before my mother asks me to delete it.” Extraits d’une Famille is a 7-minute experimental film shot on Super 8. The artist, Rhayne Vermette, describes it as a “failed attempt at creating a thematic palindrome of audio/visual samples,” continuing on to say “When working between two poles of remembering one easily gets confused”. This film was a memory-soup, the narrative constantly challenged and reframed through collage, sound and POV disruptions. We see children running around a kitchen table, then teenagers playing hockey, a young Vermette herself shutting her bedroom door. The original soundtrack, bubbling and just a little caustic, played through headphones. Extraits d’une Famille occupied the faux-living room corner of the Atelier, complete with bean bag chair, vintage TV, and a fuzzy rug. Rhayne Vermette was born in Notre Dame de Lourdes, Manitoba, and is a self-taught image-maker whose work continually builds off an architectural practice. Themes of place, time and rhythm are expressed through opulent layers of fiction, animation, reenactments and divine interruption. Her first feature narrative, Ste. Anne, won TIFF’s Amplify Voices Award for Best Canadian Feature Film in 2021. Rhayne was shortlisted for the 2024 Sobey Art Award. It is easy to see in this piece the impulses that informed Ste. Anne. If Ste. Anne is a family history told over and over through different members, Extraits d’une Famille is the artist, alone in an attic, pushing a planchette over a ouija board.

Credit to John-Finnegan Lin

H) the Miscellany

As a maximalist, I loved this part. It felt a little like throwing a birthday party for my exhibit. Vinyl decals of “Thank yous” in every featured Indigenous artist’s language adorned the walls. Fractured excerpts of Djama’s poetry emerged on the walls, with one particular line (“Hold my hand even as this world burns”) accompanied by hands cut from a holographic paper that shimmered like fire in the low gallery lights. My partner and I meticulously recreated classic protest signs that took on new dimensions thanks to messages cut from stencils and glued to cloud-patterned wallpaper, as though capturing a moment in time when they were held triumphantly towards the sky. Repurposed CCTV security camera housing bathed the space instead in the kind of blue light one might associate with scrolling after dark. Fake plants added a touch of surreality to the space. Melanie Golder’s passion flower, created entirely from scavenged items like zip ties, served as the base for projection mapping demos of natural textures (tree bark, river currents, clouds). And finally, I found an unobtrusive place to hang two framed pieces of needlework depicting Indigenous children. To me they represent every Indigenous child stolen from families and forcibly removed from the tapestry of community. They have found a place in every one of my works.

And Thanks

I would like to express gratitude to the team at Debaser, including the installation team: Rachel Weldon, Katie Manners, Sandra Ngenge Dusabe, Calum Jeacle, Nick Schofield, and Tyler Nykilchyk. Thank you also to Kelly Neale and Felicity Hauwert of Ottawa Animation Festival, to all the coordinators and programmers of Pique and, more generally, to the denizens of the Arts Court. Thank you Melanie Golder for trusting me with your work. Thank you Yasmeen Grant for dreaming with me and sharpening my ideas. Thank you to Lesley Marshall for forwarding me this opportunity, and for being a collaborator always seduced by experimentation and growth. Thank you to Silas Grenis for wielding the box cutter with surgical precision, and your writing in the margins of every blueprint. I had just finished an incredible workshop for Indigiqueer and 2-Spirit youth interested in curation a few days before I applied, and I feel indebted to my cohort and to my mentors, Dr. Heather Igloliorte, Dr. Léuli Eshraghi, and Dr. Michelle McGeough, for helping me refine my ideas. To the keepers of this beautiful unceded Anishinaabe Algonquin territory, whose ancestral systems of governance welcomed and held so many more Indigenous Nations besides, thank you for hosting this exhibit. I hope my intentions were felt. I hope we can continue to nourish and affirm one another across space and time.

Eva Grant is a bilingual filmmaker operating at the intersection of queer and BIPOC storytelling. She is an enrolled member of the St’át’imc Nation and is also of South and West Asian and European descent. She studied literature and philosophy at Stanford University, and her multimedia projects have been supported by the CBC, ReelWorld Screen Institute, BIPOC TV and Film, TELUS STORYHIVE, ImagineNATIVE, the Indigenous Screen Office and the Canadian Media Fund.

Eva Grant is a bilingual filmmaker operating at the intersection of queer and BIPOC storytelling. She is an enrolled member of the St’át’imc Nation and is also of South and West Asian and European descent. She studied literature and philosophy at Stanford University, and her multimedia projects have been supported by the CBC, ReelWorld Screen Institute, BIPOC TV and Film, TELUS STORYHIVE, ImagineNATIVE, the Indigenous Screen Office and the Canadian Media Fund.

Photograph by Berkley Vopnfjörð, 2022