Why We Gather:

Healing, Creativity, and Care in Relation to Children’s Art from Indian Residential Schools

by Jennifer Claire Robinson, Andrea Naomi Walsh, Lorilee Wastasecoot, Kii-kita-kashuaa Mark Atleo

Introduction

To Gather:

To collect several things, often from different places or people:

To put your arms around someone and hold or carry them in a careful or loving way:

To gather speed, strength, momentum, etc. to become faster, stronger, etc.:

To gather (up) strength/courage: to prepare to make a great effort to be strong or brave:

To gather yourself: to make yourself feel calm again, or ready to do something, especially after a shock or before something difficult that you have to do.

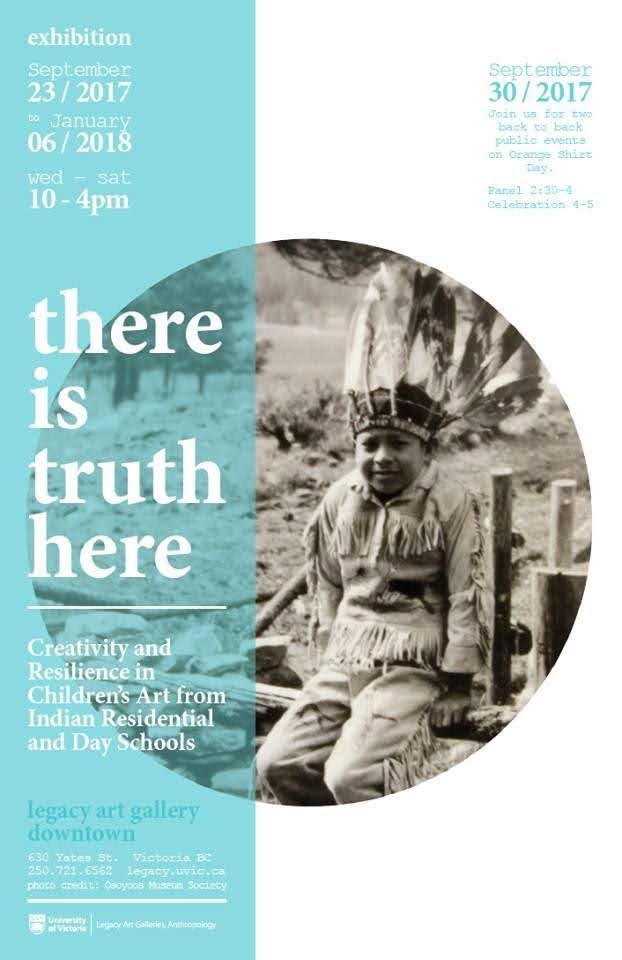

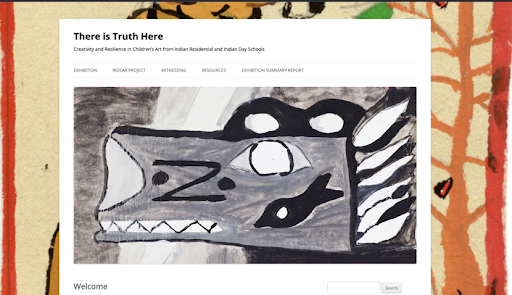

In October 2017, There is Truth Here: Creativity and Resilience in Children’s Art from Indian Residential and Day Schools (TITH) opened at the University of Victoria’s (UVic) Legacy Art Gallery in downtown Victoria, British Columbia. The exhibition showcased 63 original artworks made by children who attended two residential schools and one day school in British Columbia and one residential school in Manitoba. The range of media and content of the art was broad: delicate coloured pencil sketches depicting more-than-human beings from long ago times, gouache illustrations of contemporary life of children’s games, ranching and rodeos on paper, Indigenous interpretations of biblical stories on cedar siding shingles, and painted buckskin bags and seashells. The exhibition also included historical film footage dating to WWII of dramatic productions complete with the buckskin costumes worn by the child actors. Over 3500 visitors and close to 1000 school-aged and university students spent time in the Legacy Gallery, learning about the art on display, as well as the experiences of children in residential and day schools from Survivors and Intergenerational Survivors who led exhibition tours and took part in programming events. In April 2019 TITH opened at the Museum of Vancouver. Over the 8-month run of the exhibition, the museum recorded 65,000 museum entrances by visitors. Special to this installation of the TITH was the inclusion of Belongings from the Museum of Vancouver’s collections that included creations such as hooked rugs and wood carvings.

As co-authors of this chapter, we each played a unique role in the creation of TITH. The initial vision of the exhibition came from Andrea Walsh as a way to bring together Survivors and their families from different First Nations, with whom she had worked between 5 and 15 years to repatriate childhood art created in residential and day schools. She worked as lead curator in the exhibition. Jennifer Robinson completed her PhD under the supervision of Walsh, and a significant portion of her dissertation research was guided by Alberni Indian Residential School Survivors. Jennifer worked as curatorial researcher for the exhibition. Mark Atleo (Ahousaht First Nation) is a Survivor of the Alberni IRS (AIRS). He chose to exhibit his repatriated childhood painting in the exhibition, advised the curatorial team on label text, spoke to media on behalf of Survivors, and participated in Survivor-led educational programming. Lorilee Wastasecoot (Peguis First Nation) worked through her position at the Legacy Art Gallery as Curator of Indigenous Collections and Engagement as well as being the daughter of Jim Wastasecoot, a Survivor of the MacKay IRS, who consented to have his repatriated painting on exhibition. Lorilee curated the section of the exhibition dedicated to the MacKay IRS paintings in collaboration with Survivors of the Mackay Residential School Survivors Group, Inc. (MRSGI).

Eight years after the initial exhibition of TITH, our co-authorship of this chapter presents an important opportunity for us to gather reflections on how the TITH exhibition informs our ongoing community-engaged curatorial and collections work including repatriation and education initiatives. In particular we consider how, and what we have learned together through our fostering, inspiration, and participation in acts of gathering – as witnessed through our relationships with, and care for, generous people and precious works of children’s art. In this chapter we focus on the acts of gathering that informed our work with paintings repatriated to Alberni IRS and MacKay IRS Survivors leading up to TITH and in the years after. Our chapter celebrates work we have done together which is anchored by our individual cultural, experiential, and professional identities and locations. This collective work requires us to value each other’s unique knowledge and perspectives, and how we share these with each other. We respect that our knowledge and experience cannot (and at times should not) be shared by all members of the group for reasons of personal choice and/or cultural safety. For these reasons, empathy and respect are important values that underpin the reflections in our work and in our writing here. Reflections on our experiences of gathering deserve careful consideration for the ways these acts suture our collective work in repatriation, education, and exhibitions, to the creativity and resilience of individual children, who created the art that has inspired us to work together.

In 2012 Survivors of AIRS and their families joined UVic Elders in Residence, students, staff, and faculty members in a gathering of support for the repatriation of children’s paintings created at the AIRS in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The AIRS paintings formed part of a larger collection of Indigenous children’s artworks collected by the artist Robert Aller, who taught extra-curricular art classes at the AIRS as a volunteer at the school. Following Aller’s death in 2008, his family gifted the collection of paintings to UVic[1]. Between 2012 and 2013 repatriation of the AIRS paintings was facilitated through support from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s (TRC) Commemoration Funding, and the TRC’s invitation to exhibit paintings from the Alberni IRS at regional and national TRC gatherings. Survivors and faculty from UVic, expanded their repatriation work in 2014 to include Survivors of the MacKay IRS in Dauphin, Manitoba, and their families, faculty from the University College of the North (UCN) and leadership within the Keewatin Tribal Council (KTC); children’s paintings from the Mackay IRS formed part of the Aller Collection of artworks gifted to the University of Victoria. Since 2012, the Visual Stories Lab in the Department of Anthropology at UVic, with support from University Art Collections, has provided a place of care for artworks and people in our work.

Under the guidance of Survivors and their families, our primary focus remains the repatriation of artworks from the Aller Collection. In collaboration with local and national museums, archives, cultural centres, and Survivor-run nonprofit societies we have created multiple exhibitions of the children’s art, in addition to public and school-based educational programs. The work of repatriation has fostered relationships that are foundational to our curatorial collaborations and exhibitions. Together, repatriation and exhibitions have in turn supported our inquiry and understanding about the creation of the artworks and their role in reconciliation and healing in private and public contexts (see Walsh 2020, 2023).

While the TITH exhibition presented our work in public settings of galleries, the success of the collaborations was in large part made possible because of the (ongoing) relational work undertaken outside or away from contexts of public viewing. In the intervening years since the TITH exhibitions, it has become more evident that gathering remains a pivotal part of our collective curatorial and relational practices with the children’s art and each other. This is especially important as the nature of our work and the constellations of people working together evolve.

Pathways into our use of gathering as methodology are informed by perspectives shared through Indigenous frameworks for relational knowledge production and academic considerations around education and reconciliation in Canada. For example, Walsh and Robinson have been influenced by ideas that position concentrated acts of coming together, set with intention, as opportunities to produce new meaning and facilitate learning (Hager and Mawopiyane, 2021; Parker 2018). We all remain guided in our work first by the culturally specific teachings shared by Survivors around their paintings, supported by Indigenous ways of knowing and being that centre coming together in good relation, to share and receive knowledge, as the heart of Indigenous methodological research practice (Walsh 2023; Wilson 2008; Wilson et al. 2019). In doing so, we honour stories and storytelling as the basis for sharing lived experience and Indigenous histories (Archibald 2008; Van Camp 2021), including the honouring of generational and intergenerational experiences of residential and day school (Linklater 2014, Thomas 2000, 2005). We are also reminded when we come together, how we carry all that we are as individuals, which includes our experiences and knowledge, but also our vulnerabilities (Georgeson-Usher 2023).

In this chapter, we identify five acts of gathering that have been essential in our together:

1) Gathering Marks: The gathering of marks made on paper by Indigenous children while attending Indian residential and day schools across Canada. Here we pause and reflect on the efforts to gather understanding of how collections of children’s art from residential and day schools came into existence, and what work is, and will be, required for their return to the people who created them.

2) Gathering Truth: We emphasize the gathering of truth from Survivors and their families, and the honouring of the lived experience related to the ongoing impacts of colonialism in everyday lives of Indigenous peoples and communities.

3)Gathering Through Exhibitions: We look to how when we gather around artworks in the context of exhibitions and related programming, this creates opportunities to both witness the creativity and resilience of children who attended these schools and the continued impact of these schools on Survivors and their families.

4) Gathering Together: The informal gatherings that form the backbone of our work together.

5) Gathering Reflections: We end this chapter with our personal reflections where we consider what we have learned from one another and what this work has meant to us individually and collectively.

“To gather,” as the dictionary reference opening this chapter defines, is an act that brings people and things closely together, in ways that can build strength and courage, so that we may carry each other in a careful or loving way (dictionarycambridge.org, 2025, emphasis added). As we look back to TITH, to the lessons learned in creating this exhibition, and how to how we have continued to gather since this time, working with care and love remains central to our methodology.

Left: TITH Legacy Art Gallery Exhibition Poster from 2017. Above: TITH Digital Education Resource, 2017.

Gathering Marks

The artworks in TITH originated from both private and institutional collections. Drawings, created by children of the Osoyoos Indian Band (OIB) who attended the Inkameep day school (formerly on the OIB reserve near Oliver, B.C), were loaned from the private collections of OIB families and the Osoyoos Museum Society. The U’Mista Cultural Centre loaned drawings created by children at St. Michael’s Indian Residential School (formerly located at Alert Bay, BC.). Paintings from the Alberni IRS and MacKay IRS were selected from repatriated artworks to Survivors from the Aller Collection. Permissions for exhibiting the art in TITH came from individuals who created works as children, their families, or in the case of works unattributed to individuals, such as those from U’Mista collections, the Centre provided consent for display.

We recognize for Indigenous individuals and families that our work together is part of a much larger colonial story where the significance of Belongings held in institutional collections extends far beyond any official records of acquisition and exhibition. Indian residential and day school art collections, represent the very people, relationships, and ancestors who attended these schools and may often exist as the only remaining material traces of these childhoods. In 2012, through the VSL, Walsh and Robinson created an institutional survey sent to museums and archives across Canada inquiring about collections of Indigenous children’s artwork in their care. At the time of this research, we identified nineteen collections of artworks created by children. We must assume that through the work of the TRC that more collections have been identified but recognize they remain a rarity. We maintain the belief that cultural and educational institutions that hold these collections must make extraordinary efforts to highlight them within their own agendas of reconciliation, particularly considering collections such as these do not sit neatly into any clear category of institutional collecting, cataloguing, or curating. At times collections and artworks therein, are most often not identified in records as belonging to an individual or to a particular community or nation. Of note is the way in which children were moved often great distances from their homes, and too, those adults who ‘collected’ the works of children (largely through their professions) often moved themselves after their time in the schools. The latter movement of individuals often moved collections of children’s art created in one part of Canada to other locations in the country (where they were deposited into archives or museums) that were completely unassociated with the place of the art’s creation. Many collections do not have names associated with the makers, which makes identifying families for possible research and repatriation challenging. Given these challenges, we remain mindful to pause and reflect on the lessons learned in gathering artworks such as these from Survivors as to how to care for these unique collections.

Given this context we respect the children’s artworks as Belongings, and when they are revealed through collections research, they are first and foremost someone’s property. Our thinking engages the work of anthropologists who viewed objects of material and visual culture, such as artworks, as having social lives (Appadurai 1986) and agentive qualities (Gell 1998). Such artworks they theorized, existed as key actors in networks of human interactions. We are drawn to research that finds artworks, Belongings, and the everyday things that make up archives and collections, as objects capable of building relationships and facilitating social healing (Peers 2013). These artworks have relational qualities; they are sensorial, they are meant to be touched, held, and engaged with to both understand past encounters and create new meanings (Edwards 2012; Million 2009). As such, we have come to understand works of art such as those on exhibition in TITH, as having the possibility to act as nodes through which some relationships are born, others healed, and others, possibly reconciled (Walsh 2020). In our work with collections, we acknowledge and prioritize, the importance of Indigenous oral histories that give life to cultural Belongings and ancestors in archives and museums (Hunt 2016). As residential and day school material continues to be researched in institutional collections, we are mindful to keep the focus on these works, whether they be artworks, audio cassettes, photographs, or archival documents, as being “people centred” (Weber 2019). These artworks are about children; they are not just marks made on paper. We have therefore, in our work together, centered the experiences of Survivors and their families and prioritized the importance of gathering the truth from Survivors themselves as part of the life story of each artwork.

Gathering Truth

Survivors and families who guide our work with children’s artworks intentionally set our focus to be on the creativity of the children as expressions of their knowledges, identities, and experiences. We were taught explicitly that the exhibitions must never illustrate the history of residential schools. In the context of community driven curatorial projects and engaged research around collections of objects or artwork created during periods of duress, violence or trauma, concentrated acts of listening builds relationships that centre trust and care between curators, researchers and those sharing their truth (Lehrer et al., 2011; Robinson 2018; Selfridge et., al. 2021). What we heard from Survivors assisted in the formation of exhibition text that appeared in labels and panels about the artworks from the perspectives of Survivors and families. Importantly, it is these moments of concentrated acts of listening that create the trust needed to allow for the sharing and gathering of truth, and through that trust, the building of relationships. Most of this listening occurred in the years leading up to TITH; interviews were not conducted as part of the exhibition’s preparation. Rather, Walsh brought together the information shared by Survivors of the Alberni IRS through their collective work with the TRC, and repatriation of the artworks, or, sitting with OIB families for over 15 years prior as she conducted research with Elders who attended the Inkameep Day School.

Gatherings focused on listening as a form of witnessing Survivors’ truth through artworks, were seen in the form of educational programming that accompanied TITH for public schools. Our commitment to gathering students with Survivors to make personal connections began with the 2013 National Event for the TRC in Vancouver. Survivors of the Alberni IRS, alongside Anthropology students from UVic participated in the educational forum for Vancouver schools; a multi-day event where Survivors and UVic students set up a display of the paintings, shared private collections of photographs owned by Survivors, and handed out summaries of the paintings’ origins and the story of their return to learners. The estimated number of students from lower mainland schools visiting the education forum was over 5000. This personal engagement between Survivors and students continues through annual exhibitions of the paintings in collaboration with Vancouver Island school districts as part of programming for National Day for Truth and Reconciliation/ Orange Shirt Day. These educational forums are sponsored by the non-profit society created by Alberni IRS Survivors and supported with grant monies from annual applications to Canadian Heritage for support from Commemoration Funding.

Gathering Through Exhibitions

Collaborative exhibition building began with Alberni IRS Survivors shortly after paintings were returned through the show To Reunite, To Honour, To Witness at the Legacy in 2013. This exhibition was followed by, We Are All One at the Alberni Valley Museum 2014-2015 (Walsh 2020, 2023), and TITH in 2017 and 2019. In 2017 selected AIRS paintings were used to create a digital exhibition alongside videos of Survivors speaking about the paintings and their return in the permanent Canada Hall exhibit at the Canadian Museum of History (CMH) in Gatineau, Quebec. The paintings and the Survivors’ narratives were placed in the chronological display of Canada’s history, where they serve as an example of reconciliation efforts.

Prior to the re-opening of Canada Hall in 2017, Survivors from AIRS and members of their families, along with Walsh, Robinson, and Bradley Clements (then a graduate student of Walsh’s) travelled to the museum in 2015 to create the CMH content under the direction of Dr. Jamie Trepanier, Curator of History of Childhood and Social Movements. This trip coincided with the official celebrations surrounding the release of the TRC’s Final Report in June of that year. On that occasion the CMH hosted Survivors and fellow travellers for an evening of truth telling with Survivors’ sharing their experiences at the Alberni IRS and speaking in person about their work to return of paintings. For Survivors, the chance to speak to the public about the paintings at the national museum was an important event; yet, what is remembered of that night by Survivors is the way they gathered to support one member of the group to give his two young granddaughters, who live in Ottawa far away from their ancestral home, their Ahousaht names. In this example, the Survivors and their families utilized the public CMH gathering as a ready-made audience of witnesses. He carried out a powerful act of cultural survival – the naming of his grandchildren – in a way that would forever forward connect them to place and family. The ability to name the girls in front of Nuuchahnulth people who were part of the travelling group was also important as they would take home this information about the girls. This naming is taken up in detail by Clements who travelled with the group as part of his work with Survivors towards his M.A. thesis (2018: 61-65).

The importance of Survivors, family members, and UVic faculty and students travelling together cannot be understated. While the truths of the individual Survivors who created paintings is displayed through exhibition texts, the work to repatriate the paintings, and then to create exhibitions is collectively experienced. And it was through a common vision that the paintings were valuable not only to Survivors and families, but that they would be valued by others, who didn’t share their experiences of the schools. It was never questioned that almost 20 Survivors and their families would travel together, learn together, create together, and supported each other in the process of making the truth of the paintings and the story of their return one of public history.

Photograph above: the group at the Canadian Museum of History visiting the new Canada Hall, Gallery 3, where an installation of the AIRS paintings is located, October 2017.

When situated in the context of art, archival, and exhibition work that addresses difficult and sensitive subject matter, TITH provided a space for visitors to witness the experiences of residential and days schools as well as the lived experiences of navigating the legacies of colonialism today. As a place of encounter, TITH is an example of how exhibitions can have the great potential to contribute to the “pedagogy of witnessing” of difficult histories (Simon 2014). As modes of education, exhibitions like TITH, create avenues for the public to engage with the Calls to Action from the Final Report released from the TRC (2015), beyond the framework of government agendas of reconciliation. Rather, TITH provided a visual and tangible record of the resilience of the children who attended these schools and the experiences of Survivors, and their families as told in their own words. In this capacity, TITH created the possibility for corporeal and sensorial experiences with children’s art and archives, where the audiences could move beyond only simply the visual consumption of objects and things, to understanding exhibitions and archives, as scholar Dian Million (2009) argues, in ways that are “felt”. If colonialism is a process “experienced by the body” as L’Hirondelle Hill and McCall argue, (2015:16), gathering, with the artwork and with our bodies, has the potential to teach new ways of understanding the impacts of Canadian colonialism on Indigenous peoples. Exhibitions such as TITH, have the potential for transformative learning that takes place through the whole body.

In addition to the educational programming for students, the programming agenda for TITH included public events at the Legacy Art Gallery and at the Museum of Vancouver, as well as private, family-oriented events hosted by the galleries. Gathering in the space of a gallery, where for a public event or for a private meeting, has the potential to create opportunities for teaching, listening, and enacting of practices of care within the walls of the institution.

Whether visitors came to take an exhibition tour with one of the Survivors, attend the public opening and panel discussion of Survivors, artists, and researchers, or took part as students in curriculum relevant programming on residential schools, TITH created important opportunities to hear the truth about residential and day experiences from Survivors and their families from different parts of the country and to spend time with artwork created by children representing multiple nations and communities. From this perspective, time spent with Survivors and with the children’s artworks, can provide points of departure from which to begin conversations about how acts of conciliation, that is, the coming together for the first time in the context of truth telling, engaged listening, and sustained relationship building (Garneau 2016), can be created through curatorial practice. The picture below is from our private Survivor gathering that took place in the Legacy Art Gallery, which created the space for participants to share a lunch together, and then as we sat in a circle that included Survivors and their families, gallery staff, UVic faculty and students, we shared experiences of residential and day schools, encountering the artwork, working on this exhibition, and our goals for the future, all being surrounded by the art. Survivors have continually stressed the physical art is an extension of the child; as such there was a sense throughout the gathering, that the child artists were present in these gatherings. Importantly, gathering has been an essential working methodology that has brought Survivors and their families together with curators, researchers, and students to care for one another, and doing so, reconfigure institutional ways of working that allow for exhibitions like TITH to be possible.

Photograph of Survivors of the Alberni IRS, the MacKay IRS, and the Inkameep Day School and their families at the Legacy Art Gallery during a two-day long family gathering through the exhibit, photo courtesy of Shelley Chester, 2017.

Gathering Together

Over time, members of the group have taken part in various public gatherings such as exhibition openings, public programmed events through museums or galleries, conference presentations, and presentations given to school aged children, university classes and community organizations. And while, TITH as an exhibition space, is an example of a very public facing kind of gathering, where artwork is curated in a formal gallery space, many private, smaller gatherings fostered the relationships that made this exhibition possible. This way of working together, through engaged relational encounters, began well before the exhibition opened and has continued long after its closure (Walsh 2023). These private moments of gathering have directly come to inform our public events. Examples of these gatherings include many meetings, where the group has gathered in museum meeting rooms or cultural centres. There have been gatherings in many restaurants and cafes, and it is this gathering around a table with food that has come to be one of the key successes to sustained relationship building. These gatherings put us in good relation so we may care for one another (Walsh 2023) while also celebrating Indigenous ways of gathering that come with eating, feasting, gifting, tea, coffee, and a sense of spending good time (Van Camp 2021). There are gatherings made over the phone, gatherings as a check in on the day, family, health, and achievements. These connections take place through text messages complete with emojis, through the power of social media, and through our private Facebook pages, which help with the planning of events. Since the time of TITH, we encountered the challenges faced during COVID-19 when the ability to gather in person with our bodies, was not possible and so moved we our relationships into to digital spaces, where what it meant to gather in a time of physically not gathering, took on a new form through Zoom.

Importantly, as result of these collections of children’s paintings, a community has been created that brings people into relationships that exist outside the framework of institutional work and project development. This loose community is fluid, and non-structured. It is a community that shifts in participation and comes with the flexibility to move in and out of being actively involved in any kind of gathering. When this community was first forming back in 2012 around the Aller collection of artworks in order to work on repatriation efforts, engage in community research, and produce exhibitions, it became clear that some Survivors or their family were not interested in taking part in this work, and some made very clear requests to not be contacted again. A core principle in this shared work together, has remained the acknowledgment and respect for silence as an active form of participation.

As we continue to gather with the artworks and with each other, we have built a community of knowledge sharing and collective witnessing that has it is centre, relationships of care and a commitment to truth. Several students have been formally trained under the guidance of Walsh through the UVic, where they have had the opportunity to gained experiences from working directly alongside the AIRS Survivors, MRSGI, and through the artworks held in institutions. This ongoing community-engaged collections research and repatriation work has also been shared by Walsh, Survivors, and fellow researchers and students in several ways including the documentation of particular institutional collections (Walsh 2005, 2009; Wenzel, 2016), descriptions of curatorial projects (Walsh 2005, 2017), and highlighting Survivor experiences with museum collaborations at the Canadian Museum of History (Clements 2016, 2018) and the process of repatriation (Clements and Walsh 2019; Walsh 2020, 2023). This work has also been positioned in the context of human rights, social activism, and reconciliation in museum and curatorial practice (Robinson 2017, 2018, 2019; Walsh 2020), and alongside the growing field of Indigenous curatorial practice in Canada and elsewhere (Walsh 2023). For those of us that work through public institutions, as educators, curators, researchers, and students, we are committed to bringing forward this methodology of careful listening and sustained relationship building, into our work. As Sarah Hunt reminds, “this is what it means to be a witness – stepping up to validate what you have observed when an important act is denied or forgotten” (2018:284). In this sense, the act of critical writing is also itself, a form of gathering; the bringing together of ideas and lessons learned from doing this work into resources that can be shared within the larger collections-based repatriation and reconciliation practices taking place in Canada.

Photograph above: Alberni Residential School Society members enjoy a Christmas breakfast together at Smitty’s in Port Alberni, B.C. 2023.

Gathering Reflections

Through our personal reflections on the TITH, we offer three perspectives: Lorilee and Mark share personal stories of the gatherings leading up to the show, which fostered healing while also sparking ongoing questions and dialogue; Andrea reflects on fundamental shifts in our relationships to the paintings by Survivors from objects in collections to Belongings of Survivors, and the imperative to persist in centring the children’s artworks and Survivors’ truths in education initiatives for young and older peoples; and Jennifer examines how gatherings influences exhibition delivery and curatorial practice.

Mark

In 2012, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was being held in Victoria B.C. This was an emotional year for me, as the TRC was the same day as my Residential school settlement hearing. Following the conclusion of the TRC, in Victoria, I was notified by my friends who also attended Alberni Indian Residential School (AIRS) the same years as me about the paintings. Most of us played the same sports in school and became lifelong friends. Jack Cook, Jeff Cook, and Wally Samuel phoned me to tell me that there was a painting that belonged to me, and to contact Professor Dr. Andrea Walsh to go view the painting, to confirm that it was mine. Andrea told me that it would be returned to me in traditional ceremony at Truth and Reconciliation Commission Hearing in Vancouver in October 2013.

In 2015, the AIRS group of paintings were shown at Alberni Valley Museum which opened as We Are All One show. We were also invited to attend the Final Report of the Commission Hearings in Ottawa that same year and to make a video for the Canadian Museum of History. In 2017, we went back to Ottawa to see the final installation of our stories on video being displayed at the museum. In the fall of 2017, we had a gathering at the Victoria Legacy Gallery which was showing There is Truth Here with other families and schools. In 2018-19 with Carey Newman and Kelly Richardson we did a film project for education purposes on video for the Canadian Museum of History. In 2018, I travelled to the University College of the North in Thompson, Manitoba with Wally Samuel, Andrea, Lorilee and Jennifer to bring paintings belonging to people in that territory.

The return of my painting was an emotional time, and a big weight lifted off my shoulders, it was a big relief. The return of my painting was the beginning of my healing journey, which has brought brighter days into my life. To share my story of my experience at a residential school is like a brighter new day, much happier days. Today I’m in school for to be a mental health and addictions councillor as my goal.

Lorilee

As an Intergenerational Survivor, I have always found it hard to understand the experiences of my parents, who attended day schools and residential schools in Manitoba in the 1950s and 60s. My experiences were second-hand, yet still deeply felt as the child of Survivors. I didn’t really begin to understand what had happened through my parents’ words, but through the testimonies of other Survivors who spoke openly.

In our family, we rarely talked about residential schools. My mom and dad kept many of the bad stories to themselves, wanting to protect us from the pain of what they endured and witnessed as children and teenagers. The turning point for me came with the return of a painting my dad created when he was 10 years old at the Mackay Indian Residential School in Dauphin, Manitoba. That painting opened a window into his childhood and helped me understand his twelve years at the school in a way words never had.

What struck me most was the incredible power of the art created by these children. Each painting carried the voice of a child. One artwork I included in TITH was by a 5-year-old named “Patricia,” no last name given. On black construction paper, she painted a house with a white sun above it. The sight of it sent chills through me and brought a lump to my throat. I thought of my own daughter at that age, how sweet she was with her little bowl haircut and long black eyelashes. My heart broke when I imagined Patricia’s mother, knowing her time with her child was borrowed, that soon she would be taken away.

This is where I urge readers, especially white readers who may not fully understand our experiences, to try to put themselves in someone else’s shoes: my granny’s, my dad’s, Patricia’s. Imagine if it were your child at residential school, painting while you sat at home, hundreds of miles away. I cried thinking of my dad, only 10 years old, painting his picture in that school.

This art isn’t just beautiful, it is alive with history, memory, and truth. It can bring families and communities together, but it also surfaces the deep pain and disruption caused by residential schools.

When my dad’s painting was repatriated, it brought our family together. It was powerful and joyful, incredible to witness what he had painted from his imagination as a child. And yet it made me angry, because it also revealed the cracks left in our family by the legacy of residential schools. The art carried so much; it connected us, gave us pride, and at the same time reminded us of the grief, loss, and dysfunction we are still working through.

Many people think of reconciliation only as Indigenous peoples “making peace” with Canada. But the deeper truth is that Indigenous nations and communities need space to heal, reconnect, and reconcile with themselves, their families, and their cultures first, after the harms of residential schools and ongoing colonial policies. This is what the return of the painting and true reconciliation has meant for me; gathering with one another, facing what was taken, and finding strength in what remains.

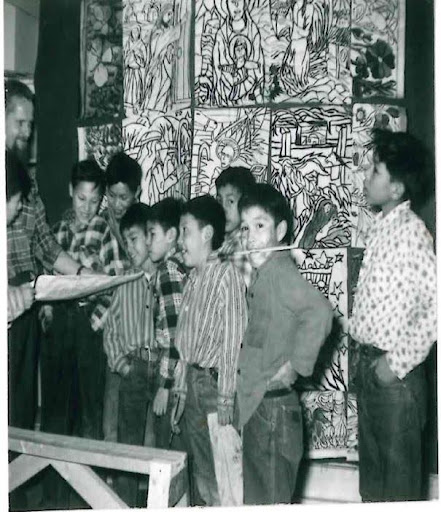

Image Right: Children in Robert Aller’s classroom at Mackay Residential School. Robert Aller pictured far left, Jim Wastasecoot beside Aller to the right.

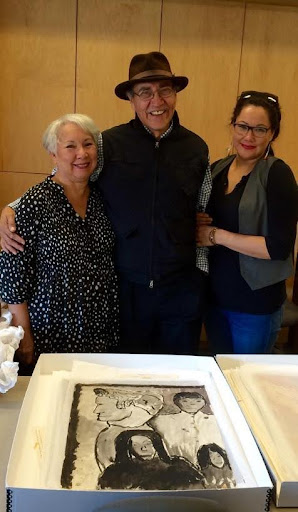

Image Far Right: Karen, Jim, and Lorilee Wastasecoot visit the paintings at the VSL at University of Victoria, Victoria, BC 2015.

Andrea

The act of gathering has played a significant role in my personal and professional transformation in terms of how I see myself making contributions to the work of repatriation and curation with Indigenous children’s artworks. Using the definition of gathering we present at the front of this chapter as a point of departure for my personal reflection, I consider below the ways by which gathering/gatherings have influenced how I understand collecting/collections, using our Survivor-led education in care-filled ways, remaining mindful how and for whom this work is strengthening, and finally how gathering is preparing us, and others who are committed to the work of reconciliation, for what lay ahead.

The artworks exhibited in TITH have in common their intersection with gathering/collecting by individuals associated with residential and day schools. These individuals produced collections that when gifted/donated to museums were named for those collectors, and/or the place from which they collected. In the case of the artworks by children who attended the Alberni IRS, the paintings were initially identified as from the “Aller Collection” or by the name of the school when they were gifted to UVic in 2008. After a major gathering in 2013 when the paintings were publicly repatriated, the naming protocol shifted. Paintings were increasingly identified by the name of their creator, and they symbolized that individual’s creativity and indeed were experienced by many as extensions of the children themselves. This movement from material to relational frameworks, from collections of objects to Survivors’ Belongings, continues to provide momentum for our work with the paintings and Survivors.

As a group of Belongings, the paintings will always be identified as formerly part of a collection because of their in-common history, their chronological or social biography. Yet our learning through the paintings is not from the perspective of the paintings as art collections. Rather I believe our education should be considered through encounters with Survivors’ Belongings. I believe Survivors guide these encounters with great care, and they create opportunities for our learning. Through large public gatherings such as the TRC regional and national events where the paintings were exhibited, or the Canadian Museum of History where Survivors voices reach thousands of members of public, or through smaller public exhibitions and programming through district and civic museums, Survivors share their truth.

Survivors’ efforts focus on strengthening public understanding of the legacy of residential and day schools on generations of Indigenous families. They and their children have told me many times over that this work to educate the public through gatherings has strengthened them, too. Yet, the repeated labour of teaching through one’s own experiences, is undeniably an exhausting experience for the Survivor, and their children, even if simultaneously expressed as healing. As I write this reflection in 2025, we are 10 years on from the release of the TRC’s Final Report, and in Canada we have been presented countless opportunities to gather, be present, and to carry our education from Survivors forward. For those of us working in the heritage sector, we must continually re-commit to working to respond to the TRC Calls To Action, and following the guidance of Indigenous leaders, such as that presented in the Canadian Museum’s Association Moved to Action Report in our public facing positions and through our work that ensures the work of Survivors is never forgotten. We must find ways to bring people together to gather with the intention to learn and share our knowledge with each other in ways that centre Survivor truths. We must consider not only the work we do now in institutions, but that this work must include succession planning for the next generation of people entering this work, committing to the work of reconciliation through their professions. How can we take the lessons learned from the ways by which we gathered with Survivors as discussed in this chapter, and apply them more broadly across our institutions?

Exhibitions and public facing programming have strengthened the education of generations of younger Canadians who in coming years will start their adult lives from very different places than their predecessors. Despite this success, in Canada we are witnessing a growing level of public statements stemming from residential school denialism. In 2024 Mark Atleo and I led a day-long professional development training session for teachers in Vancouver, B.C. Teachers at the school picked up their responsibilities, and were inspired by the educational programming Dr. James Trepanier at the CMH created with Alberni IRS Survivors, artist Carey Newman and myself. In the fall of 2025, in a school assembly of hundreds of students, a half dozen grade 2 students shared what they learned about Mark Atleo’s childhood painting of a Sockeye salmon. They spoke about Mark as a person and a Survivor; they shared what they learned about salmon for nations on the coast. They were grade 2 students teaching their peers through gathering. In 2024 a Concordia professor taught the story of the return of the paintings using a chapter I authored (2023). One of his fourth-year students studying animation created a short film in which she animated the paintings exhibited in TITH, and with permission of the Survivors, she exhibited her video in a school exhibition. In turn, she gifted the video back to Survivors for their use in educational programming through the newly formed non-profit Alberni Residential School Survivors’ Society (incorporated 2023). The animation student’s own learning will in turn support and inspire other students as the Survivors share her work in their programs.

I have learned from decades of witnessing Survivors gather and share their truth that all people, young and older, are called to witness and share the truths of Survivors, all people, young and older, are empowered to teach and learn through empathy, and all people, young and older, are called to witness. And I have learned, there is no one way to witness and share the truth.

Jennifer

My understanding of gathering as a non-Indigenous ally in this work has always oscillated between the necessity of private gatherings—whether these be gatherings meant only for Survivors and their families; the collective moments of coming together to share a meal and discuss project ideas; or say the contemplative space of researching and writing—and what I see as the potential of the public gatherings, whether they be in museums, galleries, or community events. My own relationship to this work began in the very private, introspective place that develops with research. I came to UVic in 2011 to work with Andrea as a graduate student and a part of role was to work with Aller’s personal archive so we could better understand how the paintings came together as well as helping to conduct the institutional survey of collections of Indigenous children’s artworks. Over time, my role has been fluid, including assisting with various aspects of collections research and exhibition development, and helping to host and support Survivors and their families during our events together.

When I look back to the time of the first opening of TITH in 2017, I am reminded how much was going on at this time. 2017 marked the 150th anniversary of Canadian Confederation and there was a very palpable charge amongst artists, curators, scholars, and those of us working through galleries, archives, and museums in some capacity. This was the time when the discourse of reconciliation in and through public institutions in Canada was gaining momentum. From these various engagements, both private and public, I have come to see the pedagogical potential of gathering in gallery spaces as embodied way of learning. This potential, better rephrased as responsibility, is the call for galleries, museums, and universities, as public institutions in Canada, to continue to take up complex and complicated histories in ways that create meaningful spaces of engagement for public debate and dialogue. In other words, to create opportunities to gather, in safe and respectful ways, so there is space to dialogue about the complexities of colonialism(s) and the profound legacies of which we are still witnessing today. As I write this reflection in 2025, many public institutions across the country are struggling with lower budgets, collections and gallery spaces long overdue for renewal, leadership. In the conclusion of my dissertation which I complete in 2017, I really valued the potential for museums, art galleries, public institutions to be places where people can come together to share. Part of this sharing also involves having constructive dialogues about these spaces, whether they be universities, museums, art galleries or archives, so that they can be accountable to the colonial histories of public institutions in Canada, while creating multiple points of access for diverse visitors. I still believe in this function. I believe this because I have witnessed and participated in these moments of sharing and I am better person for it.

Final Thoughts: Gathering as Methodology

This chapter has been a kind of gathering where we have brought together shared experiences of doing this work and how collections of children’s artworks have been researched through institutions and brought together for the TITH exhibition. This chapter highlights how gathering as a methodological practice, was not only crucial to the development of TITH—but creates the foundation for how constant acts of gathering, in good relation, built around trust and careful listening, are also acts of conciliation. We see how small acts of conciliations that take place over time can lead to larger moments that could be considered reconciliatory. In the story of these gatherings, both in relation to bringing together of artworks, and people, is the story of how gathering has helped to create relations. We have shared how the gathering over time around of these artworks, and with the knowledge that exists from Survivors and their families around these collections, has created network of colleagues and friends. In our individual reflections, we offer different perspectives on taking part in this work overtime. For Lorilee and Mark, their personal stories of the gatherings leading up to the show and the ways by which they produced moments of healing but also opened questions and dialogue to be continued. For Mark, the key message here, is that receiving his painting has directly been connected to his own healing and the momentum of this project has given him the courage and strength to pursue his educational goals. For Andrea and Jennifer, the generosity working with Survivors has critically shaped our ways of researching, educating, and curating, by how we have come to better under ourselves in relationship to history of Canada. In a very real sense, we have come to know one another through these paintings; the paintings have become a powerful material connection that has allowed for the fostering of our relationships with each other. The artwork has brought us together and anchored our gathering. And in this coming together, we are always learning from one other: as Survivors of residential and day schools, as Intergenerational Survivors, as researchers and students with mixed settler ancestries—as Indigenous and non-Indigenous people living in these territories in a time of so-called reconciliation—every time we gather.

Acknowledgements

The There is Truth Here exhibition was the product of many people who came together to share their personal childhood art, their experiences of residential and day school, cultural knowledge, professional skills, and institutional resources. Our gratitude continues for their contributions and gifts that allowed for our present reflections on our work together.

Inkameep Day School drawings: Jane Stelkia, Dora Stelkia, Marie Stelkia; Sherri Stelkia; Richard Baptiste, Colleen Baptiste, Taylor Baptiste; the late Irene Bryson; Charlotte Stringham; the late Modesta Betterton; Chief Clarence Louie; Brenda Baptiste; Connie Waters; Caroline Baptiste.

Alberni Indian Residential School paintings: Mark Atleo (Ahousaht); Wally Samuel (Ahousaht); Donna Samuel (Gitksan); Deborah Cook (Nisga’a); Jack Cook (Huu- ay-aht); Jeffrey Cook (Huu-ay-aht); Laverne Cook (Tsimshian); Arthur Bolton (Tsimshian); Pamela Carter (Tsimshian); Dennis Thomas (Ditidaht); Shelley Chester (Ditidaht); Chuck August (Ahousaht); April Thompson (Uchucklesaht); Gina Laing (Uchucklesaht); Sherri Cook (Huu-ay-aht); and Tim Sutherland (Ahousaht).

St. Michael’s residential and day school (Alert Bay, BC) was selected through discussions of proposed research with collections and communities in collaboration with the U’mista Cultural Centre’s Executive Director, Juanita Johnston.

Survivors from the Mackay Residential School Gathering Inc. (MRSGI) have facilitated further repatriation work of Mackay IRS paintings from the Aller collection to Survivors across Manitoba. MRSGI and their families include: Jim and Karen Wastasecoot and Lorilee Wastasecoot; Jennie Wastesicoot; Amelia Wavey Saunders; Tommie Cheekie and Sharon Cheekie; Alice Bear, Clara Kirkness, Emily Kematch, Nancy Williams, Ila Bussidor, Wendy Saunders, Hazel Nalge, Sally Saunders, Henry David Neepin, Kim Young, and Muriel Young.

Footnotes

[1]This gift of over 700 paintings created by Indigenous children between the late 1950s and early 1970s were produced in art classes taught by Canadian artist Robert Aller. After Aller’s passing, his family donated this significant collection of children’s art to the university. Most of the paintings in the collection were created by Ojibwe and Algonquin children who attended summer art camps run by Aller that were funded by the Department of Indian Affairs in the early 1970s. The university did not accession this collection. The paintings are cared for at the university in the Visual Stories Lab with the intention to continue efforts to repatriate the paintings return to Survivors and families.

Bibliography

Appadurai, Arjun. 1986.The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Archibald, Jo-ann Q’um Q’um Xiiem. 2008. Indigenous Storywork: Educating the Heart, Mind, Body, and

Spirit. Vancouver: UBC Press.

Cambridge University Press and Assessment. 2025. Cambridge University, Gather. Available Online: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/gather, Accessed December 10th, 2025.

Clements, Bradley. 2016. “The Power of Return: Repatriation and Self-representation in the Aftermath of the Alberni Indian Residential School.” Relations: A Special Issue on Truth and Reconciliation 1: 103–113.

———. 2018. Displaying Truth and Reconciliation: Experiences of Engagement between Alberni Indian Residential School Survivors and Museum Professionals Curating the Canadian History Hall. Unpublished Master’s Thesis. Department of Anthropology. University of Victoria.

Clements, Bradley A., & Andrea N. Walsh. 2019. “Something from My Past that I Saw and Recognized’: Renewed Efforts in Repatriation and Exhibiting Art from Residential and Day Schools. RoundUp: The Voice of the BC Museums Association 273:16-21. Available Online: https://museum.bc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/274-Roundup-Reconciliation-and Repatriation-Web.pdf , Accessed July 22nd , 2025.

Conrad, Diane and Anita Sinner, eds. 2015. Creating Together: Participatory, Community-Based, and Collaborative Arts Practices and Scholarship across Canada. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

Edwards, Elizabeth. 2012. “Objects of Affect: Photography Beyond the Image” Annual Review of Anthropology 41: 221-234.

Garneau, David. 2016. “Imaginary Spaces of Conciliation and Reconciliation: Art, Curation, Healing”. Arts of Engagement: Taking Aesthetic Action In and Beyond the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Eds. Dylan Robinson and Keavy Martin, pp.21-41. Waterloo: Wilfred Laurier University Press.

Georgeson-Usher, Camille. 2023. The Threshold for Gathering. Doctoral Dissertation. Department of Cultural Studies. Queen’s University.

Gell Alfred. 1998. Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory. Oxford: Clarendon.

Hager, Shirley N. and Mawopiyane. 2021. The Gatherings: Reimaging Indigenous-Settler Relations. Toronto: Aevo UTP.

Hunt, Sarah. 2018. “Researching within Relations of Violence: Witnessing as Methodology.” In Indigenous Research: Theories, Practices, and Relationships, edited by Deborah McGregor, Jean Paul Restoule, Rochelle Johnston, pp. 282-295. Toronto: Canadian Scholars Press.

Hunt, Dallas. 2016. “Nikîkîwân 1: Contesting Settler Colonial Archives through Indigenous Oral History.” Canadian Literature 230/231 (Autumn): 25–42.

Lehrer, Erica T., Cynthia E. Milton, and Monica Patterson, eds. 2011. Curating Difficult Knowledge Violent Pasts in Public Places. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

L’Hirondelle Hill, Gabrielle and Sophie McCall. 2015. “Introduction,” In The Land We Are: Artists & Writers Unsettle The Politics of Reconciliation, pp.1-19. Winnipeg: ARP Press.

Linklater, Renee. 2014. Decolonizing Trauma Work: Indigenous Stories and Strategies. Halifax/Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing.

Million, Dian. 2009. “Felt Theory: An Indigenous Feminist Approach to Affect and History.” Wicazo Sa Review 24 (2): 53–76.

Parker, Priya, 2018. The Art of Gathering: How We Meet and Why It Matters. New York: Peguin Random House.

Peers, Laura. 2013. ‘Ceremonies of Renewal’: Visits, Relationships, and Healing in the Museum. Museums World: Advances in Research 1: 136-152.

Robinson, Jennifer Claire. 2017. The Exhibition Landscape of Human Rights in Canada: An Ethnographic Study into Process and Design. PhD Dissertation. University of Victoria.

———. 2018. “Coming Undone: Protocols of Emotion in Canadian Human Rights Museology.” In Emotion, Affective Practices, and the Past in the Present, edited by Laurajane Smith, Margaret Wetherell, and Gary Campbell, 150–163. Routledge Key Issues in Cultural Heritage. London: Routledge.

———. 2019. “Institutional Culture and the Work of Human Rights in Canadian Museums,” Museum Management and Curatorship 34(1):24-39.

Selfridge, Marion, Robinson, Jennifer Claire, and Lisa M. Mitchell. 2021.“heART Space: Curating Community Grief from Overdose”. Global Studies of Childhood Special Issue: Children’s Art in Times of Crisis 11(1):69-90.

Simon, Roger I. 2014. A Pedagogy of Witnessing: Curatorial Practice and the Pursuit of Social Justice. Albany: State Univ of New York Press.

There is Truth Here: Creativity and Resilience in Children’s Art from Indian Residential and Day Schools. 2017. Webpage. https://legacy.uvic.ca/gallery/truth/

Thomas, Robina Qwul’sih’yah’maht. 2000. Storytelling in the Spirit of Wise Woman: Experiences of Kuper Island Residential School. MA Thesis. University of Victoria.

———. 2005. “Honouring the Oral Traditions of My Ancestors Through Storytelling.” In Research as Resistance: Critical, Indigenous and Anti-Oppressive Approaches, edited by Leslie Brown and Susan Strega, pp. 237–54. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. 2015. Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Volume One: Summary. Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future. Toronto: Lorimer.

Van Camp, Richard. 2021. Gather: On the Joy of Storytelling. Regina: University of Regina Press.

Visual Stories Lab. 2025. Webpage. https://visualstorieslab.ca/

Walsh, Andrea ed. 2005. Nk’Mip Chronicles: Art from the Inkameep Day School. Oliver: Osoyoos Indian Band.

Walsh, Andrea. 2009. “Healthy Bodies, Strong Citizens: Okanagan Children’s Drawings and the Canadian Red Cross”. In Depicting Canada’s Children, Loren Lerner, ed. Pp. 279-303

———. 2017. There is Truth Here: Creativity and Resilience in Children’s Art From Indian Residential and Day Schools. Available Online: https://legacy.uvic.ca/gallery/truth/witnessing/andrea-walsh/, accessed December 10th, 2025.

———. 2020. “Repatriation, Reconciliation, and Refiguring Relationships. A Case study of the return of children’s artwork from the Alberni Indian Residential School to Survivors and their families.” In Pathways to Reconciliation: Indigenous and Settler Approaches to Implementing the TRC’s Calls to Action, edited by Aimee Craft and Paulette Regan, pp.249-267. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press.

———. 2023. “Taking Good Care: Collaborative Curating and The Alberni Indian Residential School Art Collection.” In The Routledge Companion to Indigenous Art Histories in the United States and Canada, edited by Heather Igloliorte and Carla Taunton, pp. 115-125. London/NY: Routledge.

Wenzel, Abra. 2016. The Grey Nuns Northwest Territory Collection: Embroidery in the MacKenzie Valley. Unpublished Master’s Thesis. Department of Anthropology. University of Victoria.

Weber, Genevieve. 2019. “Gratitude in the Archives,”. Garland (17) December 1st, 2019. Available Online: https://garlandmag.com/article/gratitude-in-the-archives/, accessed July 22nd, 2025.

Wilson, Shawn. 2008. Research is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods. Halifax/Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing.

Wilson, Shawn, Andrea V. Breen, Lindsay DuPré, eds. 2019. Research and Reconciliation: Unsettling Ways of Knowing through Indigenous Relationships. Toronto: Canadian Scholars.

Jennifer Claire Robinson is a settler-Canadian (English/Irish/Scottish) visual anthropologist living on lək̓ʷəŋən and W̱SÁNEĆ territories. Currently, she is Adjunct Faculty in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Victoria and a Research Associate with the Visual Stories Lab, where she has contributed various curatorial, collections, education, and repatriation projects since 2012. Jennifer is also a Research Associate with the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research where since 2021, she has taken part in several harm reduction-focused projects under the Canadian Managed Alcohol Program Study. Since 2019, she has worked as a freelance consultant on behalf of museums, galleries, cultural centres, and Indigenous nations on various projects that support community-engaged advocacy through creative and participatory research methods and collaborations.

Jennifer Claire Robinson is a settler-Canadian (English/Irish/Scottish) visual anthropologist living on lək̓ʷəŋən and W̱SÁNEĆ territories. Currently, she is Adjunct Faculty in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Victoria and a Research Associate with the Visual Stories Lab, where she has contributed various curatorial, collections, education, and repatriation projects since 2012. Jennifer is also a Research Associate with the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research where since 2021, she has taken part in several harm reduction-focused projects under the Canadian Managed Alcohol Program Study. Since 2019, she has worked as a freelance consultant on behalf of museums, galleries, cultural centres, and Indigenous nations on various projects that support community-engaged advocacy through creative and participatory research methods and collaborations.

Andrea Naomi Walsh, Ph.D. is an Associate Professor of Anthropology in the Department of Anthropology and the Smyth Chair of Arts and Engagement at the University of Victoria. Trained as a visual artist and anthropologist, her research is arts-methods based and focused on visual storytelling through exhibitions and through graphic narratives produced by drawing, printing, and digital imagery. Her work as a curator focuses on the repatriation of children’s art to Survivors from Indian Residential and Day Schools. Walsh works alongside Survivors, their families and communities to co-create exhibitions and create education opportunities with the returned childhood artworks. Walsh has worked in collaboration with Survivors and district and civic museums in B.C. and the Canadian Museum of History in Hull, Que. to share stories and artworks around repatriation as a form of reconciliation. She has worked on behalf of families from the Osoyoos Indian Band for over 24 years on the story of artworks by children who attended the Inkameep Day School during the WWII era, and Survivors who attended the Alberni IRS in the early 1960s, for over 12 years.

Andrea Naomi Walsh, Ph.D. is an Associate Professor of Anthropology in the Department of Anthropology and the Smyth Chair of Arts and Engagement at the University of Victoria. Trained as a visual artist and anthropologist, her research is arts-methods based and focused on visual storytelling through exhibitions and through graphic narratives produced by drawing, printing, and digital imagery. Her work as a curator focuses on the repatriation of children’s art to Survivors from Indian Residential and Day Schools. Walsh works alongside Survivors, their families and communities to co-create exhibitions and create education opportunities with the returned childhood artworks. Walsh has worked in collaboration with Survivors and district and civic museums in B.C. and the Canadian Museum of History in Hull, Que. to share stories and artworks around repatriation as a form of reconciliation. She has worked on behalf of families from the Osoyoos Indian Band for over 24 years on the story of artworks by children who attended the Inkameep Day School during the WWII era, and Survivors who attended the Alberni IRS in the early 1960s, for over 12 years.

Kiikitakashuaa, Mark Atleo (b.1952) grew up in Ahousaht with his mom, dad, and 9 siblings. He attended the Alberni Indian Residential School (AIRS) between the ages of 8 and 16. Most of his early childhood was spent fishing with his father and around boats. It was a life that grounded him in culture and language, and a commitment to family. Commercial fishing became Mark’s career for 36 years. In 2019 he retired from work as a driver for Handidart buses after serving the community in this way for over a decade. He is presently pursuing further education in mental health and addictions support through Camosun College. In 2013 Mark joined a collective of Survivors, Elders, faculty, staff, and students led by Andrea Walsh through the Visual Stories Lab in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Victoria. Their ongoing work focuses on the repatriation of children’s art from AIRS. Mark’s own childhood painting from his time at AIRS was returned to him at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s National Event in Vancouver. Since 2023 he has sat on Board of Directors as Member at Large for the Alberni Residential School Survivors’ Art & Education Society, as well as Board Member for Victoria’s Oasis Society. Mark is a sought-after speaker and Elder for teaching youth and the public about residential schools and being strong and resilient through culture.

Kiikitakashuaa, Mark Atleo (b.1952) grew up in Ahousaht with his mom, dad, and 9 siblings. He attended the Alberni Indian Residential School (AIRS) between the ages of 8 and 16. Most of his early childhood was spent fishing with his father and around boats. It was a life that grounded him in culture and language, and a commitment to family. Commercial fishing became Mark’s career for 36 years. In 2019 he retired from work as a driver for Handidart buses after serving the community in this way for over a decade. He is presently pursuing further education in mental health and addictions support through Camosun College. In 2013 Mark joined a collective of Survivors, Elders, faculty, staff, and students led by Andrea Walsh through the Visual Stories Lab in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Victoria. Their ongoing work focuses on the repatriation of children’s art from AIRS. Mark’s own childhood painting from his time at AIRS was returned to him at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s National Event in Vancouver. Since 2023 he has sat on Board of Directors as Member at Large for the Alberni Residential School Survivors’ Art & Education Society, as well as Board Member for Victoria’s Oasis Society. Mark is a sought-after speaker and Elder for teaching youth and the public about residential schools and being strong and resilient through culture.

Lorilee Wastasecoot is a proud Ininew iskwew (Cree woman) with roots from Peguis First Nation and York Factory in northern Manitoba. Having grown up in Winnipeg, she relocated to lək̓ʷəŋən territory/Victoria, BC, in 2010. Since joining the Legacy Art Gallery in 2016, she has made significant strides in representation and engagement, culminating in her appointment as the inaugural Curator of Indigenous Art and Engagement in 2021. Her curatorial practice is built on collaborative relationships and a deep sense of care that focuses on historical and contemporary art practices of Indigenous womxn. She advocates for the rematriation of Indigenous belongings within the University’s art collection and her exhibitions, We Carry Our Ancestors (2019), On Beaded Ground (2021), and Francis Dick’s Walking Thru My Fires (2023), are testaments to her commitment to Indigenous womxn’s narratives. Lorilee is also a member of UVic’s Repatriation Advisory Committee, reinforcing her dedication to the ethical stewardship of Indigenous heritage, as well as President of the Board for the Open Space Arts Society in Victoria, BC and a part of the Indigenous Curatorial Collective Delegation Program. Her selection for the 2024-25 cohort of the Professional Alliance for Curators of Color Mentorship Program (PACC), offered by the Association of Art Museum Curators (AAMC), underscores her potential as a leading voice in the arts community.

Lorilee Wastasecoot is a proud Ininew iskwew (Cree woman) with roots from Peguis First Nation and York Factory in northern Manitoba. Having grown up in Winnipeg, she relocated to lək̓ʷəŋən territory/Victoria, BC, in 2010. Since joining the Legacy Art Gallery in 2016, she has made significant strides in representation and engagement, culminating in her appointment as the inaugural Curator of Indigenous Art and Engagement in 2021. Her curatorial practice is built on collaborative relationships and a deep sense of care that focuses on historical and contemporary art practices of Indigenous womxn. She advocates for the rematriation of Indigenous belongings within the University’s art collection and her exhibitions, We Carry Our Ancestors (2019), On Beaded Ground (2021), and Francis Dick’s Walking Thru My Fires (2023), are testaments to her commitment to Indigenous womxn’s narratives. Lorilee is also a member of UVic’s Repatriation Advisory Committee, reinforcing her dedication to the ethical stewardship of Indigenous heritage, as well as President of the Board for the Open Space Arts Society in Victoria, BC and a part of the Indigenous Curatorial Collective Delegation Program. Her selection for the 2024-25 cohort of the Professional Alliance for Curators of Color Mentorship Program (PACC), offered by the Association of Art Museum Curators (AAMC), underscores her potential as a leading voice in the arts community.