The Clearing After A Storm

Rebecca Belmore, Fringe, 2008, Cibachrome transparency in fluorescent lightbox, 815 x 2448 x 167 mm, National Gallery of Canada. In Rebecca Belmore: Facing the Monumental, Art Gallery of Ontario, 2018. © Rebecca Belmore

By Brett Graham

Rickard also asked whether Indigenous artists continue to have responsibilities to their communities. “Everyone has the freedom to make statements,” she said, but not all art “speaks to Indian communities.” She warned, “What does it mean if we do not engage with our peoples? … New storms will follow.”

“Someone must take responsibility for valuing our unique knowledge systems for the generations to come,” Rickard continued. “Otherwise can we call ourselves Indigenous?” She believes Indigenous artists, as innovators, must “participate in the ongoing transformation of our communities. Because artists are the transformers.”

Nanibush followed with a question: “We are all thinking about the complexities of our cultures… are you laying down the gauntlet to those artists who make art that grapples with our Indigenous philosophies and those who do not?” Rickard replied, “It is much easier to be Indian from a distance.” She acknowledged that good work is being done everywhere, but warned that if the most innovative thinkers abandon their communities, “then there is a real loss.”

Similar issues are present in Aotearoa. Once an artist is labelled “Māori,” there is an expectation that they remain connected to community in a “real” or “authentic” way. “Māori artists” are expected to legitimise themselves for outsiders. Rickard’s plea, however, was not about external demands for authenticity but about strengthening Indigenous communities as vital hubs of creative thought—not places drained of their knowledge.

Rickard observed that even sympathetic mainstream writers in North America often “get basic things wrong; struggle with terminology,” contributing to a “supermarket of extraction of Indigenous knowledge.” The situation is not so different in Aotearoa. For decades, Māori artists have taken for granted that a largely non-Māori network of critics and curators lacks the cultural frameworks to interpret their work—leaving Māori readings secondary or overlooked. Younger generations may be less tolerant of this.

Nanibush noted that aabaakwad was inspired by the Indigenous New York: Curatorially Speaking discussions held in October 2016 at the Vera List Center for Art and Politics in Manhattan, and a desire to continue that momentum. The earlier event took place just weeks before the U.S. presidential election; international performance artist James Luna (Payómkawichum, Ipi, Mexican-American) arrived wearing a red cap emblazoned with “Make America Red Again,” parodying the Republican candidate’s slogan. Although internationally celebrated, Luna had chosen to return to his Luiseño/Payómkawichum community on the La Jolla Reservation in California—demonstrating that global practice and community connection could coexist. Luna passed away earlier this year at age 68, and was remembered by many speakers, including Megan Tamati-Quennell of Te Papa Tongarewa, who had invited him to Aotearoa in 2009.

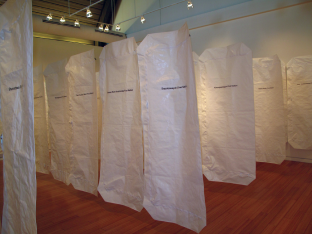

Many presentations following the keynote continued exploring the theme of “deconstructing the meta-narratives of the West.” In Hanodaga:yas (2018) by Alan Michelson (Mohawk), projections onto a bust of George Washington depict his legacy of destruction—“Hanodaga:yas,” meaning “town destroyer,” is the Mohawk name for the first U.S. president. Bonnie Devine (Anishinaabe/Ojibwa) discussed her 2010 installation Manitoba, composed of 62 suspended body bags. The work responds to a Cree community in northern Manitoba that requested medical supplies from the federal government and instead received pandemic body bags. Film matriarch Alanis Obomsawin (Abenaki Nation) discussed her documentary Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance, presenting the Oka Crisis from a Mohawk perspective. Until its release, most Canadians echoed the view of former prime minister Brian Mulroney that Mohawk protestors were “criminals… illegally wielding weapons.”

Healing after the storm was another major theme, with significant attention to the trauma caused by the Canadian Indian residential school system, which operated from the 1800s to the mid-20th century. While the assimilationist goals of Canada’s residential schools parallel those of Aotearoa’s native schools, the abuses within the Canadian boarding system more closely resemble those of New Zealand’s state-run welfare homes. Artists Robert Houle (Saulteaux) and Greg Staats (Kanien’kehá:ka), both residential-school survivors, have used art as a means of healing. “It is not easy not to judge people who have hurt you,” Houle noted.

Laughter, too, is part of healing. Lori Blondeau (Cree, Saulteaux, Métis) presented her iconic 1996 work Cosmosquaw, a photograph of herself posed on the cover of a fictional magazine. Frustrated by the lack of Indigenous representation in mainstream media, Blondeau created the work to satirise Cosmopolitan and its white, middle-class worldview. While “squaw” is often used as a slur, Blondeau reclaims the term, which derives from the Cree word iskwew, meaning “woman.” Kent Monkman (Cree) discussed his 2017 performance Another Feather in Her Bonnet, in which, as his alter ego Miss Chief Share Eagle Testickle, he “married” French fashion designer Jean-Paul Gaultier—then presumably chastised him for appropriating Indigenous headdresses on Parisian runways.

From storms to healing to humour, the discussions shared during aabaakwad were critically important for the Indigenous artists and curators in attendance. The conversations must continue. Stephan Jost, director of the Art Gallery of Ontario, has committed funding to hold the event annually for several years, hoping the idea “is stolen and multiplies.” To make that happen, perhaps we must follow the advice Wanda Nanibush offered in her closing remarks: if we truly believe in the “spirit lines that we are building,” she said, “we can shake them when we need them.”

Bonnie Devine, Manitoba, 2010, 62 medical body bags, nylon filament, laser-cut lettering. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Rickard also asked whether Indigenous artists continue to have responsibilities to their communities. “Everyone has the freedom to make statements,” she said, but not all art “speaks to Indian communities.” She warned, “What does it mean if we do not engage with our peoples? … New storms will follow.”

“Someone must take responsibility for valuing our unique knowledge systems for the generations to come,” Rickard continued. “Otherwise can we call ourselves Indigenous?” She believes Indigenous artists, as innovators, must “participate in the ongoing transformation of our communities. Because artists are the transformers.”

Nanibush followed with a question: “We are all thinking about the complexities of our cultures… are you laying down the gauntlet to those artists who make art that grapples with our Indigenous philosophies and those who do not?” Rickard replied, “It is much easier to be Indian from a distance.” She acknowledged that good work is being done everywhere, but warned that if the most innovative thinkers abandon their communities, “then there is a real loss.”

Similar issues are present in Aotearoa. Once an artist is labelled “Māori,” there is an expectation that they remain connected to community in a “real” or “authentic” way. “Māori artists” are expected to legitimise themselves for outsiders. Rickard’s plea, however, was not about external demands for authenticity but about strengthening Indigenous communities as vital hubs of creative thought—not places drained of their knowledge.

Rickard observed that even sympathetic mainstream writers in North America often “get basic things wrong; struggle with terminology,” contributing to a “supermarket of extraction of Indigenous knowledge.” The situation is not so different in Aotearoa. For decades, Māori artists have taken for granted that a largely non-Māori network of critics and curators lacks the cultural frameworks to interpret their work—leaving Māori readings secondary or overlooked. Younger generations may be less tolerant of this.

Nanibush noted that aabaakwad was inspired by the Indigenous New York: Curatorially Speaking discussions held in October 2016 at the Vera List Center for Art and Politics in Manhattan, and a desire to continue that momentum. The earlier event took place just weeks before the U.S. presidential election; international performance artist James Luna (Payómkawichum, Ipi, Mexican-American) arrived wearing a red cap emblazoned with “Make America Red Again,” parodying the Republican candidate’s slogan. Although internationally celebrated, Luna had chosen to return to his Luiseño/Payómkawichum community on the La Jolla Reservation in California—demonstrating that global practice and community connection could coexist. Luna passed away earlier this year at age 68, and was remembered by many speakers, including Megan Tamati-Quennell of Te Papa Tongarewa, who had invited him to Aotearoa in 2009.

Kent Monkman and Jean-Paul Gaultier appear in Kent Monkman, Another Feather in her Bonnet, performance, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, 8 September 2017. Photo: Frédéric Faddoul.

Many presentations following the keynote continued exploring the theme of “deconstructing the meta-narratives of the West.” In Hanodaga:yas (2018) by Alan Michelson (Mohawk), projections onto a bust of George Washington depict his legacy of destruction—“Hanodaga:yas,” meaning “town destroyer,” is the Mohawk name for the first U.S. president. Bonnie Devine (Anishinaabe/Ojibwa) discussed her 2010 installation Manitoba, composed of 62 suspended body bags. The work responds to a Cree community in northern Manitoba that requested medical supplies from the federal government and instead received pandemic body bags. Film matriarch Alanis Obomsawin (Abenaki Nation) discussed her documentary Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance, presenting the Oka Crisis from a Mohawk perspective. Until its release, most Canadians echoed the view of former prime minister Brian Mulroney that Mohawk protestors were “criminals… illegally wielding weapons.”

Healing after the storm was another major theme, with significant attention to the trauma caused by the Canadian Indian residential school system, which operated from the 1800s to the mid-20th century. While the assimilationist goals of Canada’s residential schools parallel those of Aotearoa’s native schools, the abuses within the Canadian boarding system more closely resemble those of New Zealand’s state-run welfare homes. Artists Robert Houle (Saulteaux) and Greg Staats (Kanien’kehá:ka), both residential-school survivors, have used art as a means of healing. “It is not easy not to judge people who have hurt you,” Houle noted.

Lori Blondeau, Cosmosquaw, 1996, fictional magazine cover. Courtesy of the artist.

Laughter, too, is part of healing. Lori Blondeau (Cree, Saulteaux, Métis) presented her iconic 1996 work Cosmosquaw, a photograph of herself posed on the cover of a fictional magazine. Frustrated by the lack of Indigenous representation in mainstream media, Blondeau created the work to satirise Cosmopolitan and its white, middle-class worldview. While “squaw” is often used as a slur, Blondeau reclaims the term, which derives from the Cree word iskwew, meaning “woman.” Kent Monkman (Cree) discussed his 2017 performance Another Feather in Her Bonnet, in which, as his alter ego Miss Chief Share Eagle Testickle, he “married” French fashion designer Jean-Paul Gaultier—then presumably chastised him for appropriating Indigenous headdresses on Parisian runways.

From storms to healing to humour, the discussions shared during aabaakwad were critically important for the Indigenous artists and curators in attendance. The conversations must continue. Stephan Jost, director of the Art Gallery of Ontario, has committed funding to hold the event annually for several years, hoping the idea “is stolen and multiplies.” To make that happen, perhaps we must follow the advice Wanda Nanibush offered in her closing remarks: if we truly believe in the “spirit lines that we are building,” she said, “we can shake them when we need them.”

Thursday September 13 – Saturday September 15, 2018

Baillie Court, Art Gallery of Ontario

aabaakwad (it clears after a storm) is a two-and-a-half-day event focused on shifting the current global interest in Indigenous arts to be one that is Indigenous-led. Featured keynotes are Rebecca Belmore, Wanda Nanibush, Jolene Rickard and Alanis Obomsawin. This event is centered on informal, in-depth conversations between Indigenous artists, curators and scholars from Australia, New Zealand, the United States and Canada. Guests include: Robert Houle, Adrian Stimson, Lori Blondeau, Nadia Myre, Kent Monkman, Shelley Niro, Megan Tamati-Quennell, Brett Graham, Richard Bell, Greg Staats and more to be announced. Conversations are moderated by media personalities such as Duncan McCue, Candy Palmater and Jesse Wente. Experience dynamic dialogue examining themes, materials and experiences in contemporary Indigenous art practice globally.

This event has been organized in conjunction with the Gallery’s solo exhibition Rebecca Belmore: Facing the Monumental (July 12th – October 21st, 2018).

Brett Graham (Ngāti Koroki Kahukura, Tainui, b. 1967) is a sculptor who creates large scale artworks and installations that explore indigenous histories, politics and philosophies. He has work in the collections of the National Gallery of Canada, the National Gallery of Australia, the National Gallery of Victoria, and Te Papa Tongarewa. His work has been included in the 2007 Venice Biennale (a collaboration with Rachael Rakena), the 2006 Sydney Biennale (a collaboration with Rachael Rakena) and the 2010 Sydney Biennale.

Brett Graham (Ngāti Koroki Kahukura, Tainui, b. 1967) is a sculptor who creates large scale artworks and installations that explore indigenous histories, politics and philosophies. He has work in the collections of the National Gallery of Canada, the National Gallery of Australia, the National Gallery of Victoria, and Te Papa Tongarewa. His work has been included in the 2007 Venice Biennale (a collaboration with Rachael Rakena), the 2006 Sydney Biennale (a collaboration with Rachael Rakena) and the 2010 Sydney Biennale.